Within the history of photography, especially after the Bauhaus, a set of loosely related practices have attempted to subvert photography’s stubborn literalness in recording the world before the camera’s lens. If, in the version of art history laid out by MoMA founding director Alfred Barr and critic Clement Greenberg, twentieth-century art is an ineluctable march toward abstraction, photography – painting’s insecure step-child – was not going to be left behind. For almost 60 years, Japanese-born artist Kunié Sugiura has used the raw materials of photographic printing in a manner that places her firmly in the tradition of photo-experimentation that was the legacy of Surrealism, on the one hand, and the New Vision photography of the 1920s and 1930s, on the other – a spirit and a pedagogic method that was transplanted to the U.S. at the New Bauhaus/Institute of Design in Chicago, which she attended in the mid 1960s.

At Alison Bradley Projects, Pauline Vermare, a French curator who was previously the cultural director for Magnum Photos, has assembled an intimate, career-spanning survey of Sugiura’s prodigious output. On view through May 10, the show includes Sugiura’s earliest work, the Cko series from 1966, produced when she was still a student at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. These jewel-like nude studies were inspired by the fish-eye distortions of Bill Brandt’s iconic nudes, which she saw in 1964, as well as by older Surrealist figurative work such as André Kertész’s Distortions and Hans Bellmer’s Poupées. In Cko L29 (1967), she creates a grid pattern over her distorted nude figure; set against a magenta background, the piece nods toward psychedelia and the Japanese avant-garde.

Following her move to New York in 1967, and perhaps influenced by Robert Rauschenberg and Andy Warhol, Sugiura began experimenting with screen printing photo emulsion on various surfaces – wood, aluminum, and finally canvas. Beach 2 (1971), a simple macro close-up of sand, is richly detailed and painterly, hovering gently between representation and its opposite. In her photo-paintings, she produced a carefully considered synthesis of photographic, painterly, and sculptural media. In the two examples included in the show, she combines noirish, blurry, black-and-white cityscapes with monochrome canvases, surrounding them with wooden armatures that are somewhere between minimalist sculptures and Shaker furniture.

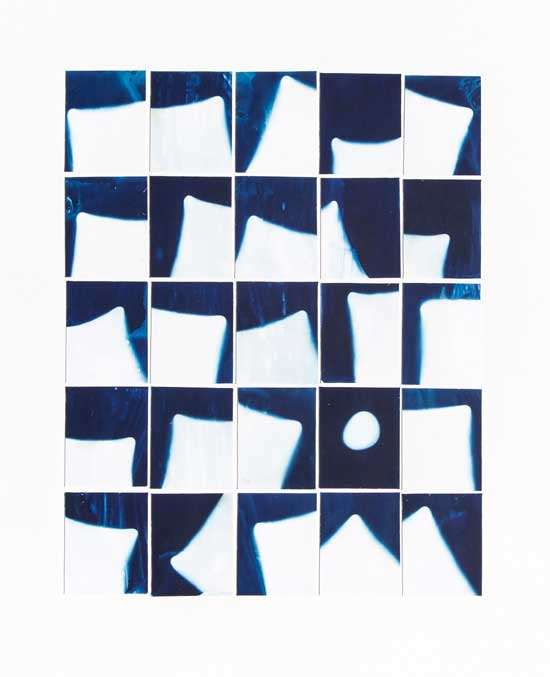

Sugiura’s pursuit of photo-experimentation almost inevitably led her to do away with the camera altogether and explore the photogram. In the series Story of Catfish (1993), she marries her pursuit of abstraction, focusing on what is irreducible in photography (light, shadow, and shape), to a sequential movement that evokes a narrative structure. As Vermare explains in the show’s catalogue, “Sugiura intended to create a visual rendition of Kishōtenketsu, the classic Japanese four-part narrative structure based on ancient Chinese four-line poetry. First, the introduction (ki); then, the development of the plot (shō); then a twist, or turning point (ten); finally, a resolution (ketsu).”

Sugiura took the photogram one step further, using it to produce the portrait series Artists and Writers, beginning in 1999. By projecting the shadows of her subjects – Jasper Johns (1999) and Carolee Schneeman (2003) – onto photo-sensitized paper, she conjures something of their personalities that evades realistic photographic representation. They encapsulate much of what is compelling in her work. Always pushing at the boundaries of the medium, she uses her subjects – whether her own body, the natural world, or her fellow humans – to embrace the fundamental contradictions of objectivity and abstraction, light and shadow, and rigorous intentionality and spontaneous discovery.