From its inception, the war on terror has been a linguistic (not to mention photographic) black hole. How do you wage an assault on a feeling or a political tactic? As the war has unfolded over 17 years, its leaders have introduced new phrases into the global vocabulary: black site, extraordinary rendition, unlawful combatants. These phrases sound clinical, potentially sinister, but without further context, it is hard to know. They are purposefully abstract, to the point of being obfuscatory. “Political speech and writing are largely the defense of the indefensible …,” wrote George Orwell in his 1946 essay Politics and the English Language. “Such phraseology is needed if one wants to name things without calling up mental pictures of them.”

The public wasn’t meant to be able to visualize the war on terror, to call up mental pictures of its machinations. What do you see when you think of it – the Twin Towers ablaze? The dehumanized prisoners of Abu Ghraib? Osama bin Laden smiling? The ominous shadow of a drone in the sky? More than a decade of this abstract war has given us a handful of images to mark its existence, but the visual lexicon remains incomplete. Artists Edmund Clark and Trevor Paglen are expanding it.

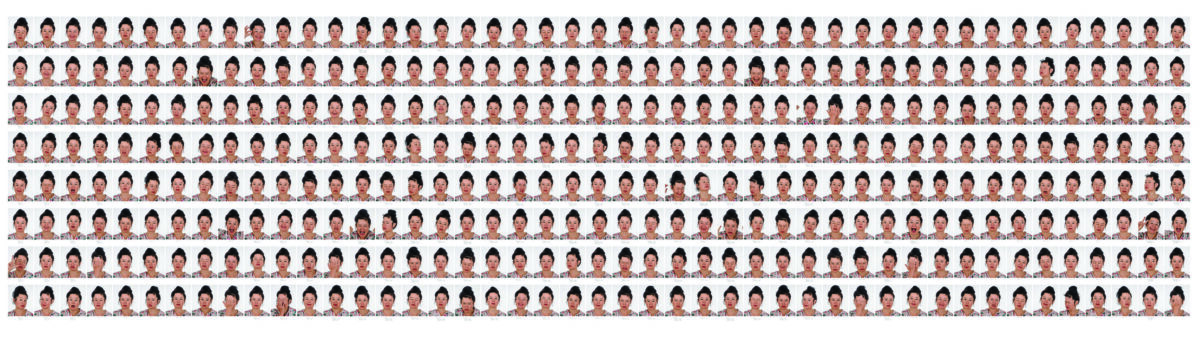

Clark began his investigation with a place that is, for many people, the locus of the war on terror: Guantanamo Bay, in Cuba. Clark – who’s having simultaneous solo shows at the International Center of Photography (through May 6) and Flowers Gallery (through March 3) in New York – visited Guantanamo in 2010, shooting both the naval base where American soldiers are stationed and the military prison where the American government has held hundreds of prisoners without trial. For his series Guantanamo: If the Light Goes Out (2010), he mixed sober, meticulously cropped photographs from those places with others he took in the homes of former Guantanamo prisoners after they’d been released. The pictures have a quiet intensity that’s heightened by a lack of people. Suggestions of human life are everywhere – from the Ronald McDonald statue that waves mercilessly outside a Guantanamo cafeteria window to rows of empty, padded shackles awaiting ankles – but, in an effort to avoid the tropes and sensationalizing of mainstream pictures of the war on terror, bodies are almost entirely absent.

As he was examining the details of Guantanamo, Clark was also thinking more broadly about systems of control. In Letters to Omar (2010), he reproduced some of the correspondence received by Omar Deghayes, a Libyan citizen, while he was imprisoned at Guantanamo. None of the letters or cards were originals: Deghayes received only copies or scans of his own mail, with sections redacted and document numbers and official stamps added. And because the correspondence came in this state, through his interrogator, he began to believe that some of it had been invented by his captors as a show of power. The childlike sincerity of the notes – a Hallmark card with a smiling cat on it, the handwritten phrase “I pray for you” – is countered by the chilling thoroughness of the bureaucracy on display.

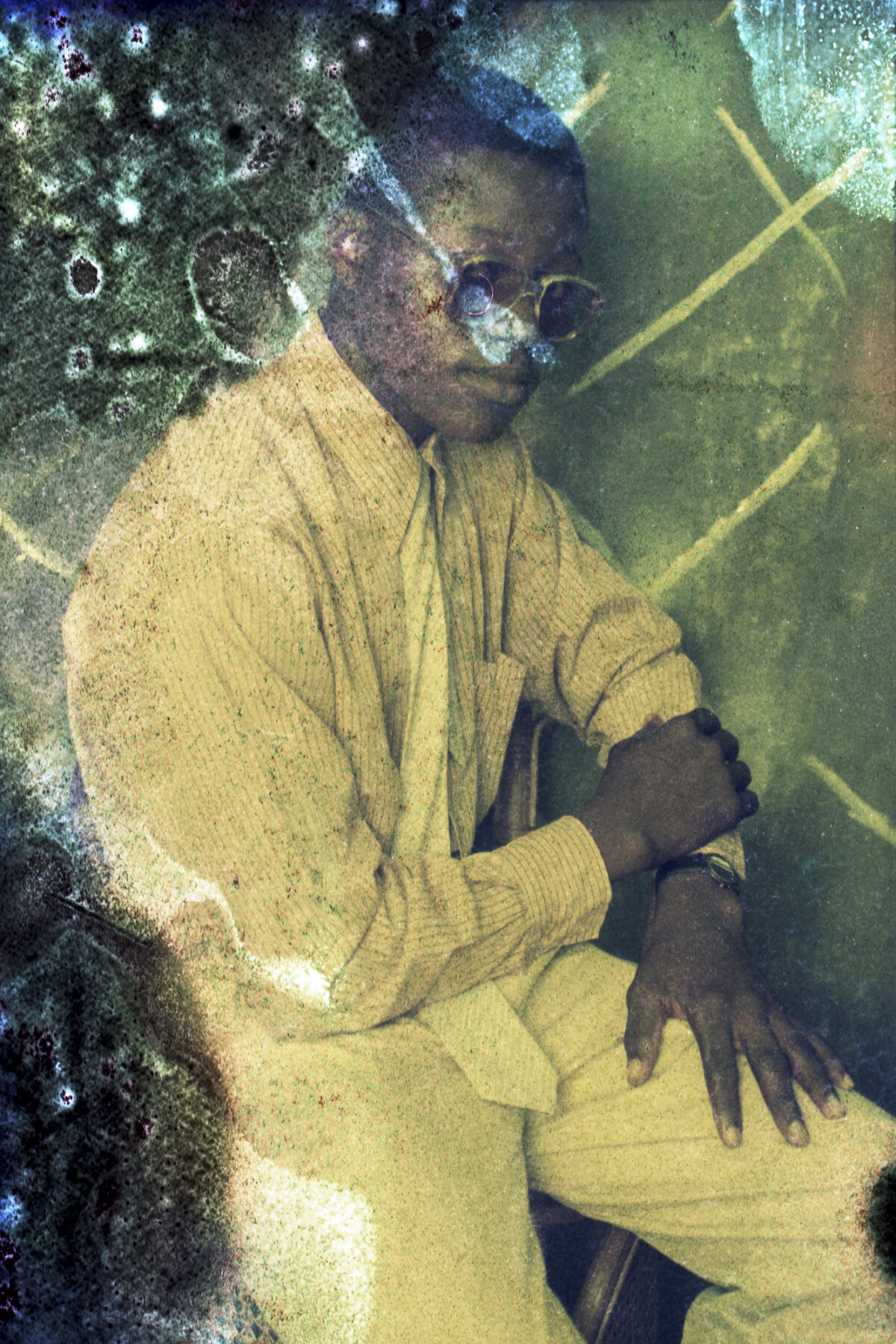

“What started as looking at what I thought was an anomalous state of exception in Guantanamo became a constant revisiting of hidden or ignored processes of detention, control, and trauma” in the wider world, Clark told Slate in 2016. Indeed, since visiting Guantanamo, Clark has refocused his lens on different aspects of the war on terror. For The Mountains of Majeed (on view at Flowers), he photographed Bagram Airfield, the U.S.’s largest base in Afghanistan, in staid images that evoke its isolation. Mountains of Majeed 4 (2014), Clark’s most abstract photograph to date, shows a weathered, impenetrable gray-blue fence separating an expanse of empty concrete foreground and a ridge of mountains along the horizon. The mountains are barely visible in the haze, appearing almost as an oasis. Their ghostly presence suggests how far removed U.S. soldiers are from the reality of the country around them.

For Negative Publicity: Artefacts of Extraordinary Rendition (2016), at ICP, he teamed up with investigator and reporter Crofton Black to trace the paths of the CIA’s extraordinary rendition program, under which, beginning in 2001, the U.S. government abducted, extradited, and imprisoned more than 100 foreigners at secret “black site” prisons in 54 countries (figures reported by the Open Society Foundations in 2013). The project comingles redacted official documents – including a table of contents that lists two sets of “Specific Unauthorized or Undocumented Techniques” for torture, among them “Waterboard Technique” and “Mock Executions” – with generic-seeming landscapes and interiors. The latter require extended captions to become meaningful: The viewer learns that a dinky blue building in one photograph houses a small flight-management company in upstate New York that provided planes for the extraordinary rendition program, and that an industrial wasteland in the shadow of the mountains in another photograph is believed to be the site of the notorious Salt Pit, the CIA’s first black site prison and interrogation site in Afghanistan. Yet the mundanity of the places captured in these images is also their point: they offer a riff on the phrase “banality of evil,” demonstrating how insidiously woven into the fabric of our world the war on terror is.

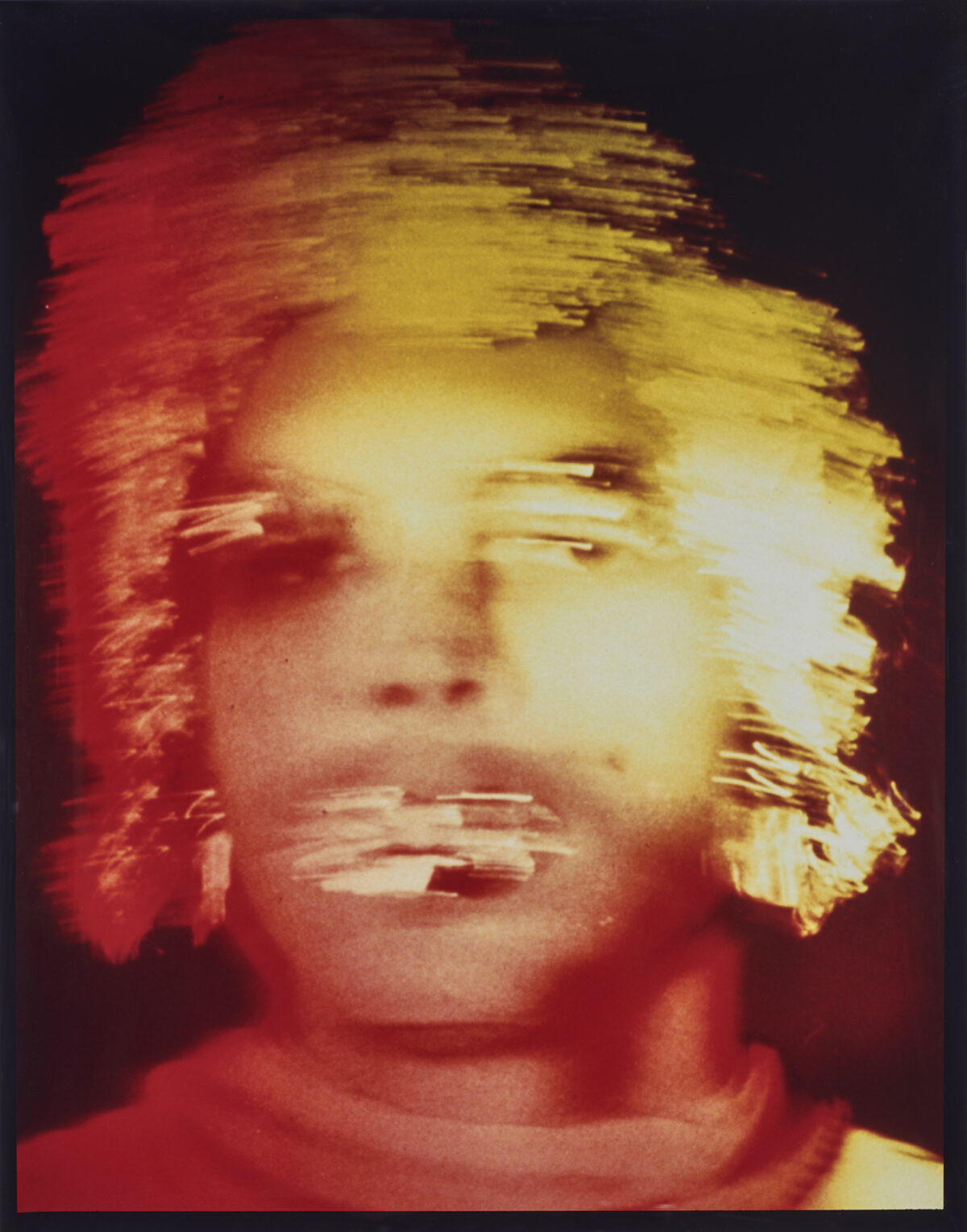

Trevor Paglen does something similar, though with photographs that are quite different. Paglen – whose mid-career survey at the Smithsonian American Art Museum opens in June – is also interested in government black sites and systems of control. He, too, went looking for the Salt Pit and the same small flight-management company in upstate New York (whose 2011 lawsuit against a business that was brokering planes for the CIA inadvertently made public a trove of documents detailing the logistics of extraordinary rendition). But while Clark’s photographs are rooted in a clear-eyed framing and focus that seem to announce, “this is our hidden reality,” Paglen’s pictures revel in a blurriness and abstraction that suggest the truth is more elusive.

For more than a decade, Paglen has photographed classified military bases and installations, mostly across the U.S. However, unlike Clark, Paglen never enters the sites he’s shooting. His training as a geographer (he has a Ph.D. in geography from Berkeley in addition to an MFA from the Art Institute of Chicago) serves him in his art practice – he finds vantage points on public land and uses sophisticated equipment including “limit-telephotography” (high-powered telescopes) to capture glimpses of his hidden subjects. The resulting pictures are often hazy or blurry, a combination of atmospheric conditions, aesthetic choices, and imposed distance. Paglen’s 2012 shot of a National Reconnaissance Office ground services station in New Mexico, which shows a light pink building with a white dome sitting atop a distant green hill, looks more like a photorealistic painting à la Gerhard Richter than an actual photograph.

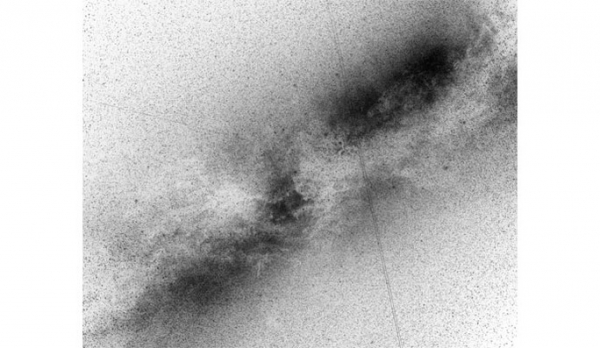

One of Paglen’s series (2010-present) features nearly abstract swaths of color: rich reds, pastel pinks, and barely-there blues, all of them the hues of the sky swept with clouds. If you look closely, however, in all the photos, a tiny black speck is visible somewhere: a drone. For another series, The Other Night Sky (2007-present), Paglen used telescopes, large-format cameras, and other technology to photograph, as he explains on his website, “classified American satellites, space debris, and obscure objects” orbiting the earth. He suggests what those “obscure objects” might be in detailed alpha-numeric titles, but the images and their subjects remain somewhat inscrutable. What the viewer sees is a whirlpool of yellow light against a red plane (STSS-1 and Two Unidentified Spacecraft over Carson City [Space Tracking and Surveillance System, USA 205], 2010) or ghostly white streaks raining down over craggy cliffs (DMSP B5D2-8 from Yavapai Point [Military Meteorological Satellite; 1995-015A], 2009).

With these images, Paglen is working in a long tradition of landscape photography; he updates Ansel Adams and Timothy O’Sullivan for the contemporary world. He allows us the sublimity of nature but tweaks it with an ominous undercurrent: the trappings of the modern “terror state,” as he calls it, so well-integrated that we barely notice them amid the beauty. “It’s about taking what might be a familiar image and reinscribing it with something else,” he told the New Yorker in 2012.

Like Clark, Paglen uses texts to help viewers understand his photographs. His titles are factual, and he often includes accompanying explanations; for example, the text for They Watch the Moon (2010) – which shows a complex of buildings so brilliantly lit they appear to be on fire, nestled among hazy but verdant green hills – states that this is a “classified ‘listening station’ deep in the forests of West Virginia” where workers attempt to capture Earth communications bouncing off the moon. By a certain measure, he knows, and wants us to know, what we’re seeing.

Yet he also wants to convey the distance between seeing and understanding. His pictures are, in their own way, general: a series of striking shots of the sky, say, with their sunsets and their drones seemingly interchangeable. Taken together, Paglen’s work documenting the terror state can feel more like a prompt to meditate on the vast, scary nature of the apparatus than an opening to learn about any of its specifics. He makes distortion a motif as much as an aesthetic choice. In a 2017 piece in T magazine, Paglen said this was an attempt to show “what invisibility looks like,” but at times it feels as though he’s also reinforcing the obscurity and impenetrability of his subject.

Clark’s work, by contrast, is awash in details. Ultimately, he’s forced to confront the same problem as Paglen – the inability of photography to show us anything self-evidently meaningful – but his solution is to incorporate documents as a way of providing information and to experiment with methods of display: Negative Publicity was first published as a book but is also displayed at the ICP as a multifaceted, research-cum-art project. Framed document reproductions of different sizes are arrayed along an entire wall, hanging above a display case that holds smaller prints of Clark’s photographs. It feels effective: knowing some things has a way of illuminating others. The informational gaps are smaller and their locations clearer in Clark’s work, because they’re surrounded on all sides by details.

Nearby at the ICP is the video Orange Screen (2016), in which Clark displays written descriptions of famous images from the war on terror against a bright orange background (the color of detainee jumpsuits). Devoid of punctuation, each one reads like a brief, horrible poem: “2001 Black smoke from a tall tower seen across roofs and skyscrapers its twin to the left intact and a plane slightly tilted black silhouetted against the blue sky.” Clark isn’t a 9/11 truther, but he wants us to reconsider what we think we know, how we’ve come to understand it, and our own complicity in this war. He isn’t giving us the images because he knows they can lie or fall short. Instead, he wants to make us call up mental pictures.