She was untrue. She broke his heart. She was after his money. Or maybe she got herself pregnant. Sometimes there’s no apparent reason for her murder. In a “murder ballad,” the folk tradition popularized in the American South in the 19th century, women go down by the river, but they don’t come back.

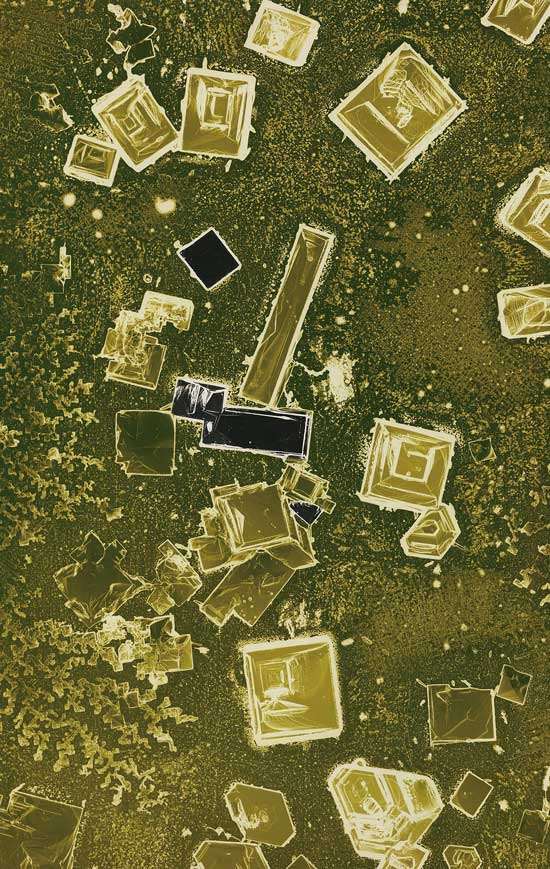

From film noir to every true-crime documentary on our streaming platforms, we love the story of a grisly femicide. Kristine Potter’s Dark Waters (Aperture, 2023) explores this disturbing titillation, projecting it into the southern landscape and resurrecting its victims. Using the murder ballad as a literary device that sets the tone, Potter dives into the vexing intersection of male violence and the American landscape.

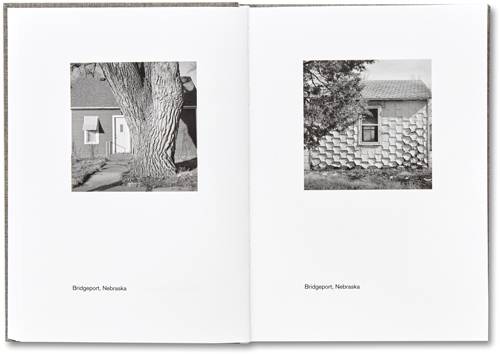

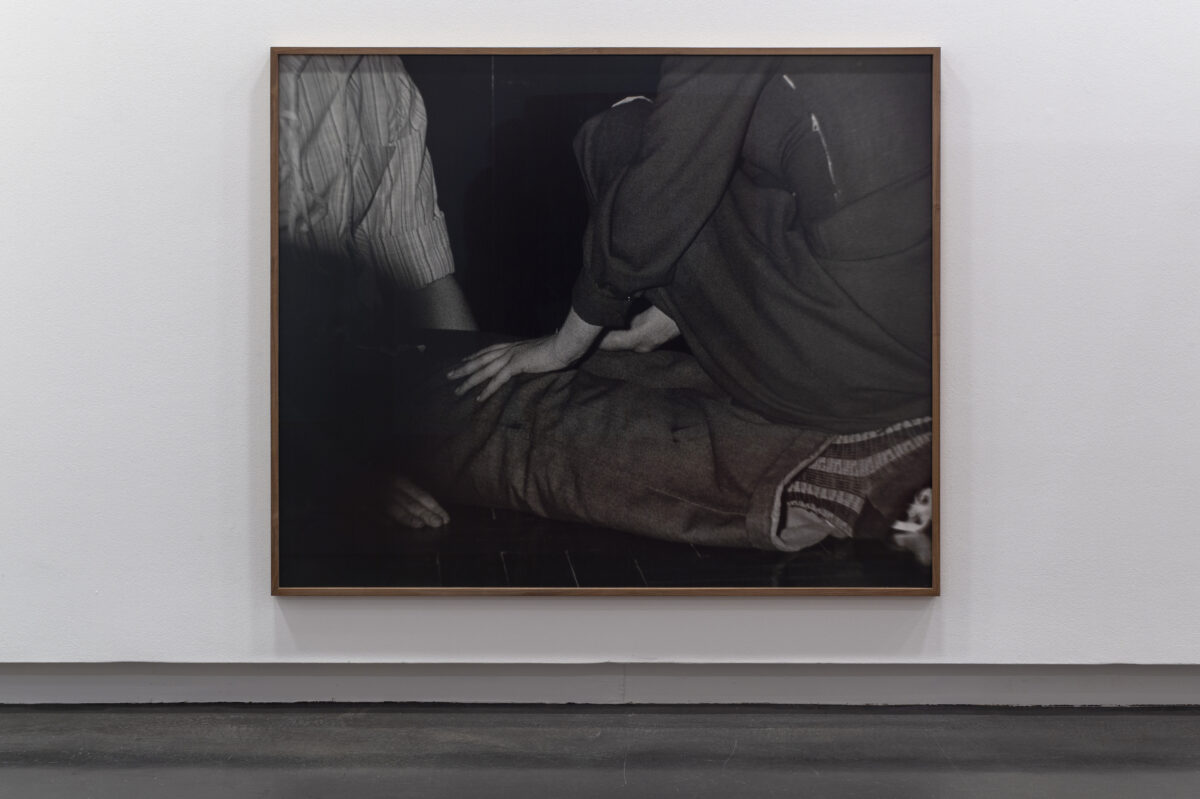

Her black-and-white photographs of Appalachian locations like Blood Creek and Poison Cove immerse us in the dark overgrowth and understory of the southeastern riverbank. Some landscapes have the stark factuality of crime-scene photos, others show lush summer woods and creeksides through a disorienting perspective, as if we’re the victim, lying uncomprehending on the ground. We meet men: fishing, fighting, and seemingly fleeing the scene on dirt roads. And we also meet the women from the ballads, many based on real-life murders, but here they are alive, river-wet, and angry.

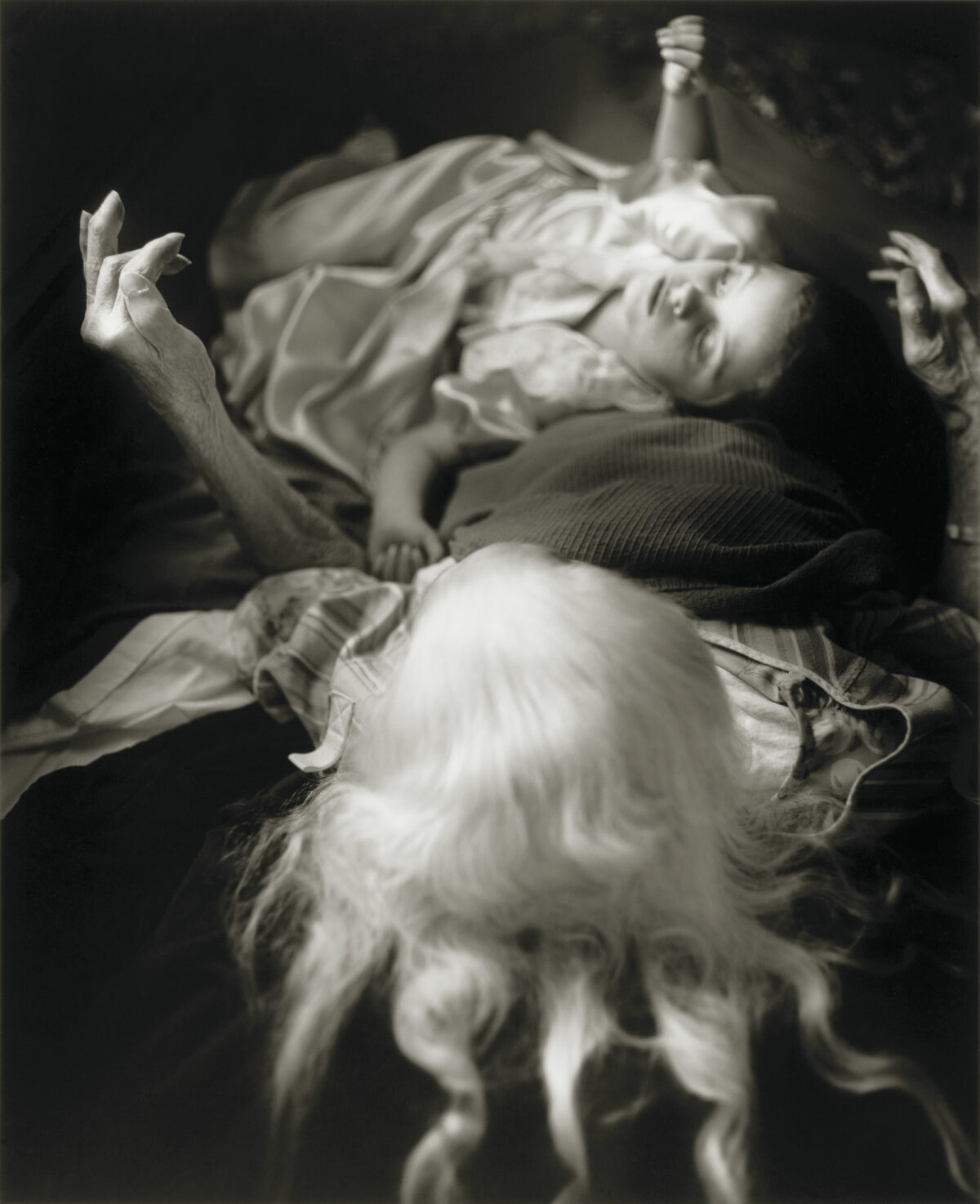

These portraits of women are made in a studio, unlike the rest of the images, and are a sort of speculative fiction in which the women from the songs address the camera with a sense of implication, even menace. In Knoxville Girl, a young woman in a lace-trimmed blouse squeezes the water from her long, tangled hair with her fists, ready to settle a score. In a photograph titled Rosie, our subject looks at the camera over the head of the plump baby clutched in her arms, dripping wet.

Dark Waters was published last summer as an Aperture monograph, a book that creates a narrative stage for these images. (The cover is literally an image of a green stage curtain, and early on we encounter a balladeer with a cowboy hat and fiddle warbling away.) Lyrics of select popular ballads are reproduced in the book with violent words crossed-out, an activation that both draws attention to the violence and negates it. The urge to add female subjectivity to these songs is further drawn out in an exhibition of the works at The Momentary in Bentonville, AK. In this immersive space, Potter has collaborated with composer Heather McIntosh on a soundscape that features cello, handclaps, and the female voice. The exhibition is on view through October 14.