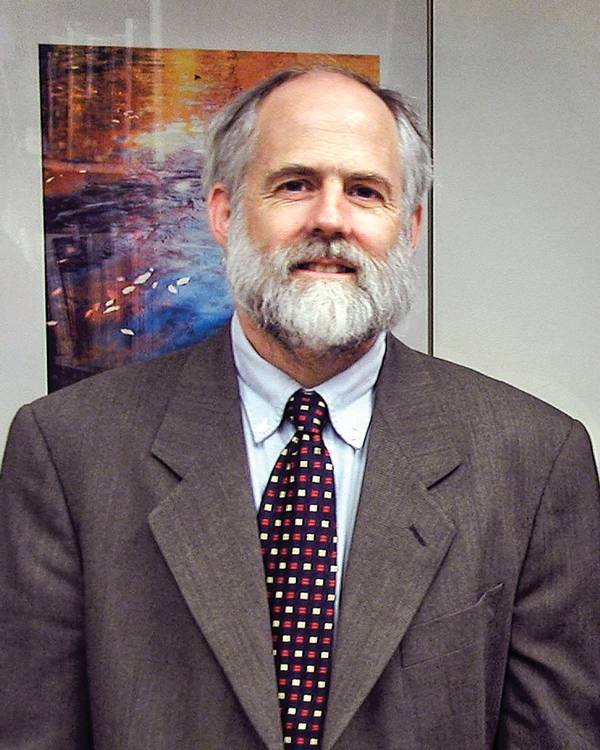

The first time John Rohrbach visited the Amon Carter Museum in 1991, he asked if he could look through some of the 250 boxes of Eliot Porter prints the museum had just received. The answer was no. Nobody had catalogued the material yet. After some persuading, he was allowed to look through a single box. He recalls pulling out a memorable photograph of a cypress tree whose trunk, in the light, was inexplicably blue. “Porter had a sophisticated sense of color that I didn’t understand,” says Rohrbach. “I thought it would be nice to explore that work some day.”

That day came not long after, when the museum called to offer him the job of organizing the Porter material. It was a three-year position that led to a full-time job that led to a book, Eliot Porter: The Color of Wildness (2001), and a 20-plus-year career in Fort Worth for Rohrbach. “What intrigues me about the museum’s collection,” he says, “is that it’s tripartite: it has strong holdings in 19th-century American photography; six individual artist archives; and a strong array of American fine art photography through modernism. These facets together offer a variety of ways of approaching the medium.”

Rohrbach first fell in love with photography when he was a high school student in Connecticut, and a friend brought him into the darkroom. “I saw that white piece of paper go into a tray of clear liquid, and then an image appeared, and I was just sucked in,” he says. He bought a camera and convinced his mother to let him build a darkroom in their laundry room. “I was just interested in making pictures,” he says. “I had no idea that there was this whole photo history.”

At Wesleyan University, he studied politics and political theory. He wound up, almost by accident, in a class on the history of prints. “That opened up a whole world for me because we spent extensive time looking at original works,” he recalls. “I realized the value of an object.”

Rohrbach got a job with the George Eastman House, then went to work at a photography commune in Millerton, New York, called Apeiron Workshops. “Everybody lived there, had access to the darkrooms, we shared the gardens and the cooking,” he says. Aperture had offices in Millerton at the time, too, and Michael Hoffman, Aperture’s longtime director, hired Rohrbach to organize the Strand Archive. When he left to earn his PhD in American civilization at the University of Delaware, he wrote his dissertation on Strand.

His background in American culture has served him well at the Amon Carter, where his next big project will be an exploration of photographic depictions of Native Americans. He has curated shows on Eliot Porter, Frank Gohlke, the New Topographics, and most recently,Color: American Photography Transformed. This year the museum commissioned Meet Me at the Trinity: Photographs by Terry Evans, about the river that runs through Fort Worth. It’s only the second show commissioned by the museum; the first was Richard Avedon’s In the American West in 1985. Not unlike that show, Meet Me at the Trinity, up through January 25, has been controversial. “The community has strong feelings about the river,” says Rohrbach. “When you get photographs that challenge your expectations, people aren’t always happy. But,” he adds, “the role of art is to surprise and challenge.”