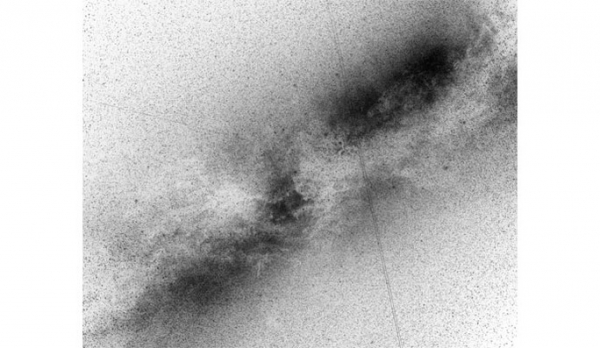

John Divola spent two years in the late 1970s visiting an abandoned house on Zuma Beach in Malibu. The house had wide, glassless ocean-facing windows, and he would spray-paint or otherwise alter the walls around them before re-photographing them. Each image in the resulting Zuma series shows the ocean through a differently colored frame, dilapidated to varying degrees. The increasing decrepitude from one image to another makes more sense when you realize Divola had an unofficial collaborator, though he didn’t know it at first. Each time he returned, the house was increasingly burnt; it turns out the local fire department was using the house for training.

Divola falls somewhere between New Topographics photographer Lewis Baltz and Gordon Matta-Clark, known for his “building cuts.” He’s rigorously systematic, yet iconoclastic and open to chance. This combination can have magical effects: in Zuma #9, the charred, peeling ceiling and debris-strewn floors contrast with the bright blue spray-painted stripe and a sunset view of the Pacific in vivid purple, pink and blue. This photograph hangs in the Pomona Museum of Art, until December 22, part of John Divola: As Far as I Could Get, a retrospective in three parts spread across three locations.

The show spans from early work he made after studying with the process-oriented, Pop-obsessed Robert Heinecken at UCLA to recent work. The Pomona section, dominated by the Zuma series, gives a view of Divola as an adventurer with a camera, transforming abandoned pockets of the built environment.

The Santa Barbara Museum of Art section — and view through January 12 and organized by curator Karen Sinsheimer, who spearheaded the whole retrospective — includes older 1970s abandoned-home images, and the newer Dogs Chasing My Car in the Desert and Theodore Street series. These two series — the first of running dogs he photographed by holding a camera out a car window, and the second of a vandalized home that he photographed using a gigapan camera that stiches together hundreds of images to make dense panoramas — suggest an experimenter preoccupied with his medium’s technical range.

The section at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, on view until July 6, occupies just one small gallery and features most prominently the series As Far as I Could Get. Divola would set the ten-second timer on his camera, then run off into the distance, “as far as he could get.” This means his back is always receding, near the center of formally appealing views of brush or desert. He’s a performer trying to escape the photographic frame while also making “good” compositions.

If only all three parts were not spread out across 130 or so miles, so that these views of Divola could intermingle more immediately. You’d get a robust feel for how he turned photography into a vehicle for often-painterly, sometimes law-bending performance while still adhering to the formal look typical of “straight” photographers, and you’d be impressed by the dexterity of his balancing act.