Karen Jenkins-Johnson has a pretty optimistic view of our current financial crisis. Perhaps the MBA she earned from the University of California at Berkeley (a degree she considered to be a personal prerequisite to entering the gallery world) has something to do with that. Not to mention the fact that she is a certified public accountant (CPA). “We’ve had several economic setbacks,” says Jenkins-Johnson, who runs two eponymous galleries on two coasts (one in New York, the other in San Francisco), “and we got through them. The thing is, you have to be wise about how you do it. People need to realize that running a gallery is a business, and to operate a business successfully you have to re-create it every three years. You have to challenge yourself and say, ‘How can I make it better?’ In that light, even the economic downturn can be helpful.”

Jenkins-Johnson, a stylish woman of 48 (who favors Prada shoes of pink suede instead of the ubiquitous Chelsea black), is one of the few African-American female entrepreneurs in the photography world. Music, not art, played a major role in her life growing up in a middle class home in Portland, Oregon. She attended the University of Puget Sound in Tacoma, Washington on a music scholarship but soon put aside the muse in favor of more practical concerns. Business (“a good, ‘respectable’ career”) became her major, and immediately upon graduation in 1982, she spent the next five years working as a CPA for Big Eight firms such as Price Waterhouse. “However, I just wasn’t happy,” she opines. “Something wasn’t right.”

In 1983, the same year she passed the CPA exam, Jenkins-Johnson took a trip to Europe, and it proved to be transformative. “I was blown away by the churches, the museums, the art,” she says, adding, “I got the bug.” Inspired, Jenkins-Johnson decided to combine her two loves, business and art, and to better prepare for entrepreneurship, she got that MBA—only to graduate in 1989, when the art market went south. Instead of striking out on her own right away, she spent the next few years, from 1990 to 1993, learning the ropes of art sales in the nationwide chain galleries Circle and Dyansen. Later, from 1993 to 1996, she became marketing director for Caldwell-Snyder, the contemporary art gallery with spaces in California and New York, learning what she calls “the back end of the business, the nuts and bolts,” which included, among other things, “doing the press releases, the marketing planning, persuasive writing, and advertising. People think you can just come in and do this, but it does really take a great deal of planning to promote an artist in the way a collector can understand.”

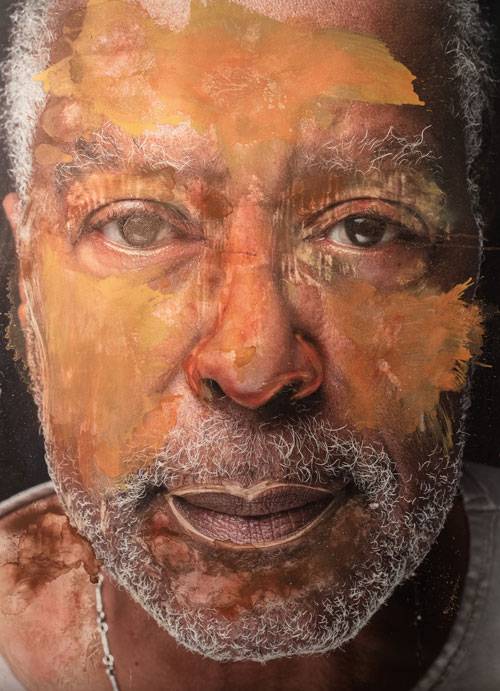

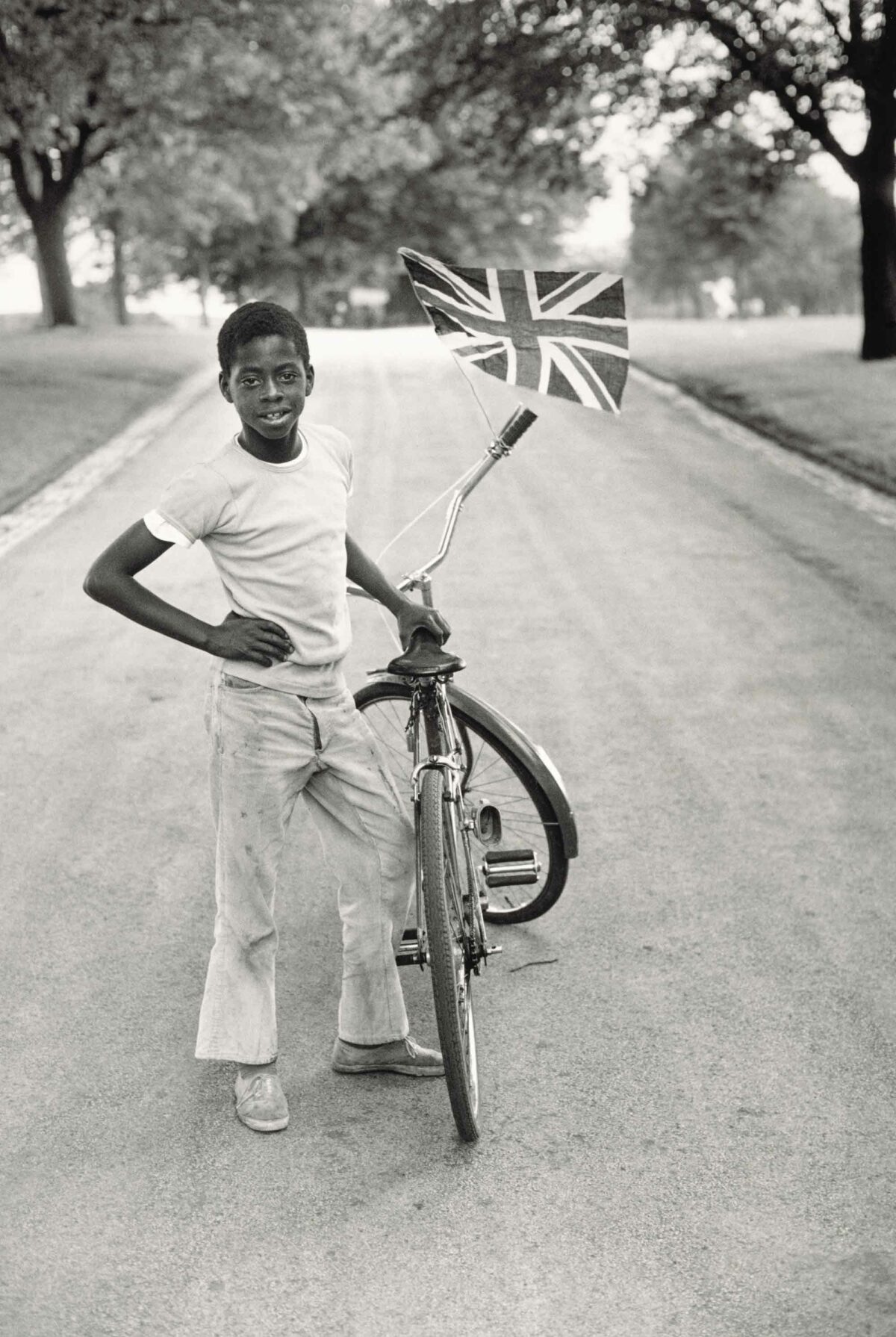

The first Jenkins-Johnson gallery opened its doors in San Francisco in June 1996. But it was the January 2006 show at her Chelsea space that really put her on the photo-world map: she showed works by Roy DeCarava from the 1940s to the 1970s that had not been seen in New York since 1996. Jenkins-Johnson was heartened by the public reaction and has since sought out more African-American artists to show, both contemporary and historical, like James Van der Zee (whose work she also showed in 2006). “Van der Zee introduced Americans to black life,” she says. “We have Christmases, deaths, births, family events, graduations. People didn’t know how we live. Among collectors, I know there’s not a whole lot of demand. But that’s going to change. I think the Obama family will bring down all the walls.”