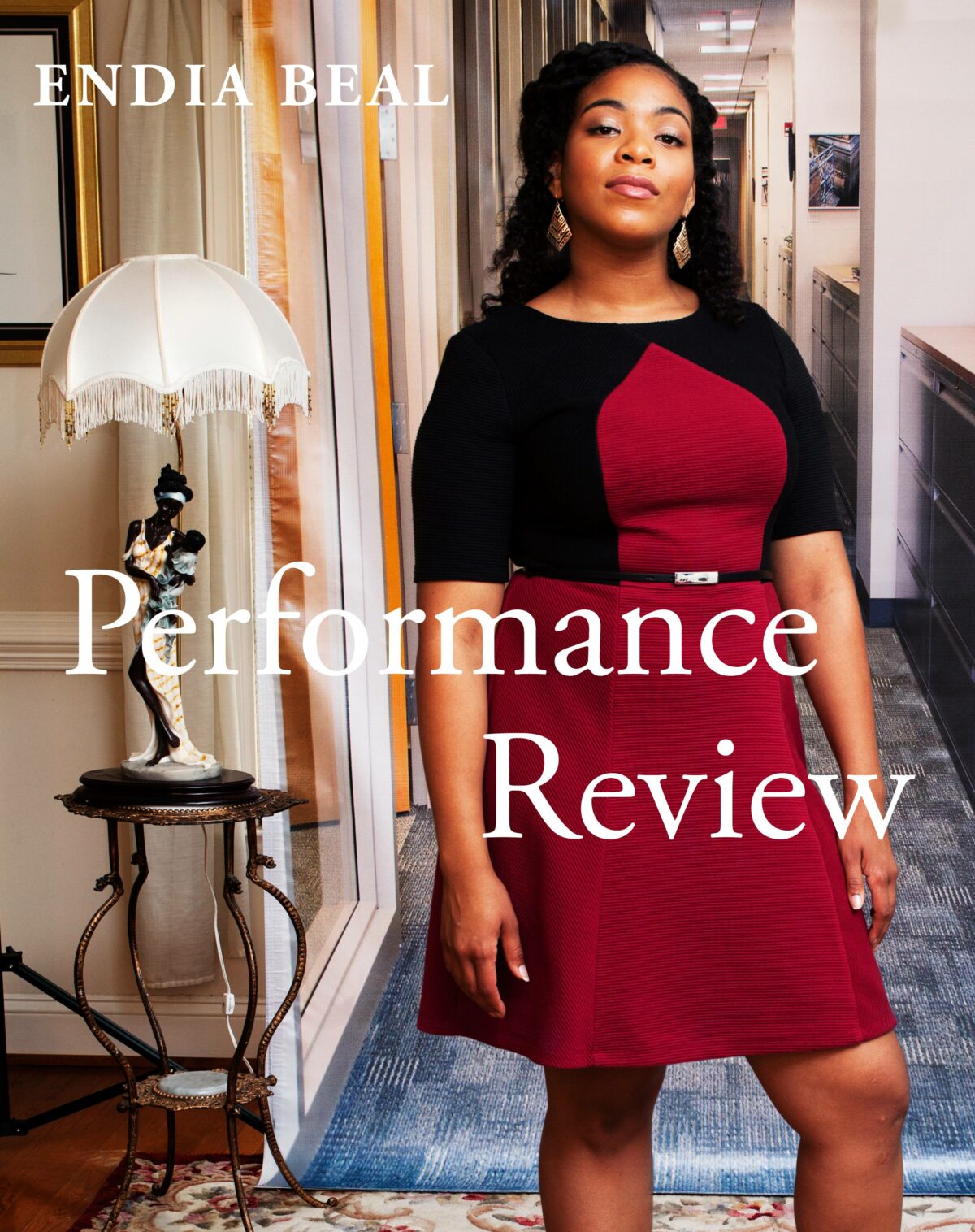

Diane Arbus famously remarked that making a photograph of someone was the right kind of attention to pay them – at the very least it was a gesture of recognition. Since she began making pictures seriously in 1991, Liz Johnson Artur, who lives in London but was born in Bulgaria of Russian and Ghanaian parentage, has been paying the right kind of attention to people and moments in her life, making sure they do not slip into oblivion. Focused largely on people of the African diaspora, a selection from her growing archive, as well as two videos, are on view at the Brooklyn Museum through August 18 in an exhibition titled Dusha, the Russian word for soul.

Lyle Rexer: Down the corridor from your exhibition in the museum is another very different photographer-archivist of his experience, Garry Winogrand (Garry Winogrand: Color, through December 8). I wouldn’t say you share much, but it is eye-opening to compare your approaches, especially to street photography.

Liz Johnson Artur: I was struck by that. I don’t often think of Winogrand in relation to my work but since you mention it, I see interesting things. Photographing on the street reflects how I move about, not just what I see but what I experience. I am always thinking about the relationship between the photographer and the subject. I would say that I am much more visible in my photographs than Winogrand was.

LR: I think I understand what you mean. I always get a sense of you interacting with your subjects, of being present to them. That may be one reason why there is such positive energy in your photographs, an exchange of sympathy.

LJA: My presence is so important to my photographs. It’s not my intention to hide behind the camera or just observe. And for the most part I stay away from candid moments. I need to be visible to my subjects. I started out not wanting to be seen, and it took me awhile to get up the confidence to engage the people I wanted to photograph. That came with experience. I want them to respond to me. There’s always a barrier with someone you don’t know, but interest, appreciation, and respect can create a relationship, even if it’s only for a moment. So I always ask my subjects not, “Can I take your picture?” but “I would like your picture.” And it’s true, I would. I am interested in them. As part of the African diaspora myself, I focus on those subjects. I gather them in the Black Balloon Archive. But my interest lies deeper than that. What is a black balloon? Something that gets my attention, that stands out and prompts a question about what I see. You know the old idea about the camera stealing the soul, well, I don’t want to feel that I am stealing anything. I have to be open and honest. I need a moral code in order to work.

LR: Not to go on about this, but it couldn’t be more different from Winogrand. If you look at the video of him at work, there is a weird diffidence about him, as if the last thing he wanted was to be impeded by his subjects.

LJA: And the other thing was, he left that huge batch of unprocessed film! That would be difficult for me. I need to see what I have done. I need to see the people I have photographed, each and every one, because I am trying to give them a context, a reference point for what the moment might mean.

LR: I see that in the exhibition. It explains why you have taken the effort to develop your own film and print it, why you keep pictures in notebooks in a variety of different formats and spend time on the display of the work in installations.

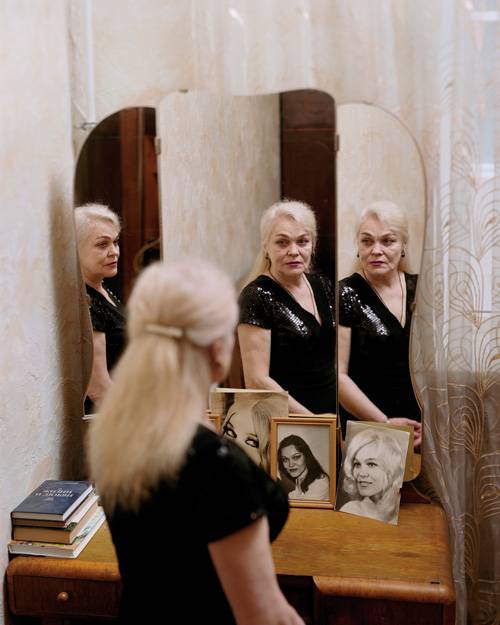

LJA: I am serious about facts – that’s what I call these experiences I photograph, these people. They form the basis of my archive. But how I keep the pictures and deal with them is just as important. It is tactile. I have related to photographs that way since I was young. I put prints in workbooks so I can go through them, put them in a context. We make so many pictures now that just disappear.

LR: In terms of that ambition to prevent experiences – images— from disappearing, I think of Wolfgang Tillmans’s famous quote, “If one thing matters, everything matters.”

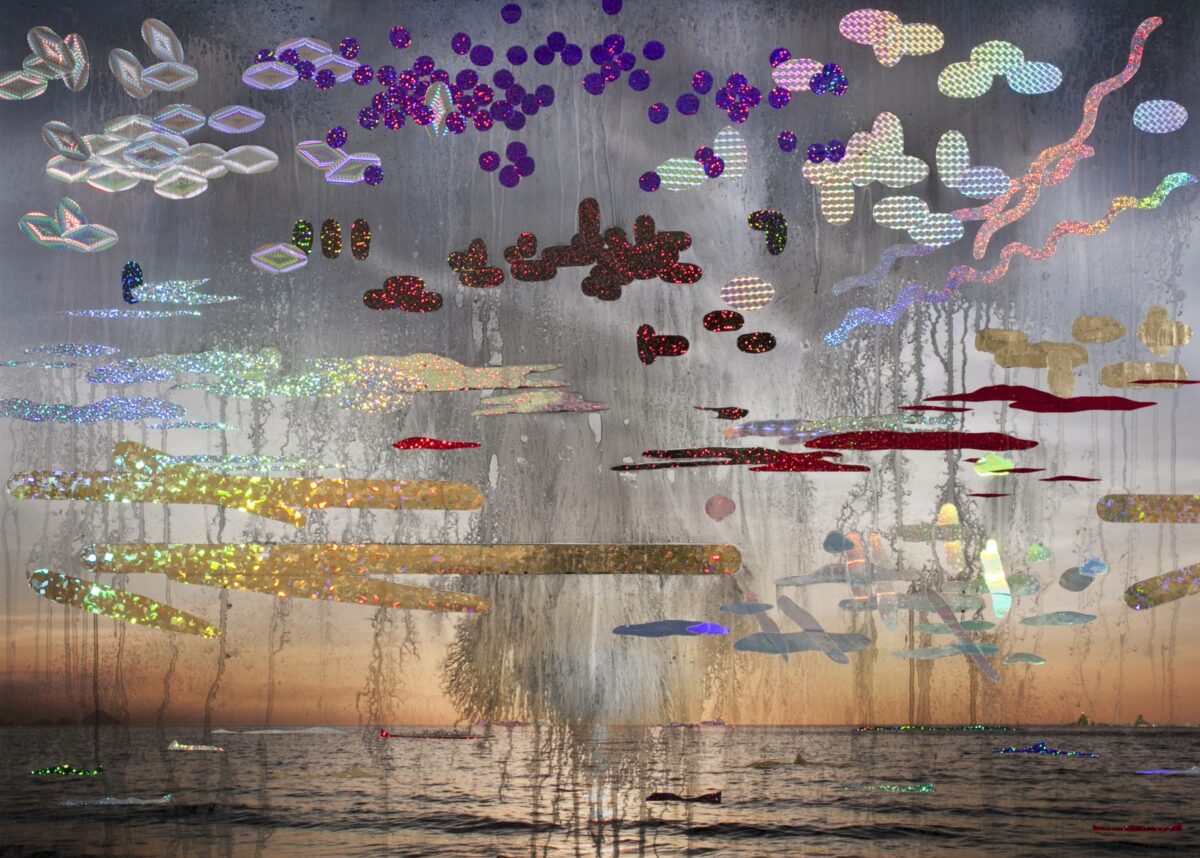

LJA: But I’m the opposite of Tillmans! Yes everything matters, but things matter in different ways and each thing, each person, is particular. That’s what I try to convey in my installations and in my workbooks. I arrange images and formats to tell stories, even if those stories are only fully readable by me. And I like to use non-photographic materials for printing because I want to offer many levels for people to relate to the photographs.

LR: There’s a lot of freedom in what you do.

LJA: Freedom is crucial to me. I had a strict, traditional analogue photographic education, and I had to worry about how to get the perfect negative and the best print. But I felt if I take this process to another place, I can open up and engage with the kind of experience that stimulates me and keeps me interested. To take another example, I never liked conventional framing in an exhibition of my work. It’s too rigid. It implies a permanent selection of images and the exclusion of others. I like to choose what I show based on what I feel at the time, just as I shoot a person or a situation based on how they strike me at the time and what questions they provoke.

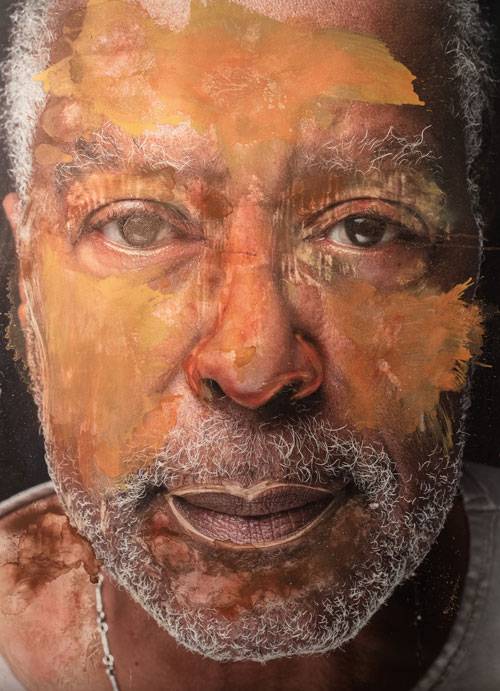

LR: There are two photographs in particular I wanted to ask you about. The first is a very dark black-and-white portrait you made of the Ghanaian photographer James Barnor in 2018. He nearly disappears into blackness!

LJA: Can I make a confession? He’s such a generous man, and I have so much respect for him. When I went to see him, I felt so invasive, with all my equipment. But it turned out that the shutter on my still camera was broken, and I just couldn’t ask him to do it all over again. I had no choice but to go with it. The picture was almost gone. But then I got to thinking about a story he told me about losing his negatives in Ghana. It is painful to lose negatives, and in a sense we as photographers are always engaged in attempting to save what’s there, whatever remains. So I decided to give the photograph a try, to salvage it, and I found in developing it that there was something there of him. It was just enough. It felt right.

LR: The other photograph is the very large inkjet print on vinyl titled For Grenfell (2017), with a shadowy, outstretched hand. It seems to hover over the entire exhibition.

LJA: I want that. I want people who come to the exhibition to ask about it, so I can tell them what it means. As an African and an immigrant, I regard Grenfell Tower [the public housing project that burned down in London in 2017] as part of the ground I walk on. I lived in public housing myself at the time, and my building was condemned as unsafe after the fire. This photograph is my comment and my moment to mourn. To go back to what I said earlier, each person is singular and has a presence. I want my pictures to stand for something. I want them to stand the test of time. I want them to testify to that singularity.