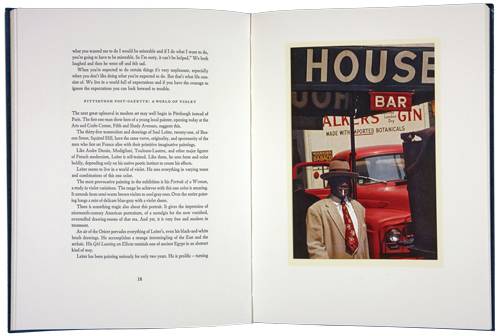

The young Emirati photographer Farah Al Qasimi has had solo shows in the last year in Houston and Boston, but through May 17, attentive New Yorkers will encounter her photographs as they make their daily way through the city, at 100 bus shelters in all five boroughs. For this Public Art Fund commission, the artist, who works between Brooklyn and Dubai, created 17 photographs for a series she calls Back and Forth Disco, centered on neighborhoods in the city that have substantial immigrant populations. (Before New York City’s galleries were closed to prevent the spread of the coronavirus, her work was also scheduled to be on view at the Helena Anrather Gallery on the Lower East Side in March and April.) The pictures revel in color, pattern, and the adornments and decorations that become cultural signifiers of a given neighborhood – two Styrofoam mannequin heads with color headscarves, for example, or the leopard-print headscarf worn by the subject of Woman in Leopard Print.

There’s a lot going on in that image: the riot of color and pattern, the blingy fingernails, and the single eye looking back at us through the mirror of a compact. Qasimi’s photographs often contain pictures within pictures, frames within frames, and the reflections of mirrors and windows. They pose the question: who looks, and who is looked at. In Five Star Barber Shop, the barber and his client are reflected in the reflection of a mirror and bracketed by two posters with a grid of headshots advertising men’s and women’s hairstyles, one example of the way Qasimi effortlessly folds the visual language of advertising into her photographs. “I feel we learn a lot about people by understanding shopping and commerce,” she said in an interview with Document Journal in 2019, and her photographs seem to push back against those who would judge the pleasures of shopping or the visual feast provided by certain corners of consumer culture.

Take the beautifully disorienting Ceiling Mirror. A purple halter dress (selling for $9.99) hangs from the ceiling next to a mirror the length of the ceiling itself, which reflects racks of colorful clothes on the floor below. If you look carefully, you can see a couple of people browsing, but they’re upside down and distorted by the mirror. The faces of Qasimi’s subjects are almost always concealed: a protective gesture, a refusal to grant viewers full access. In Bodega Chandelier, a security camera stares back at viewers who gaze at the ornamental light fixture, trying to square the elaborate decor with a store that sells Pringles and Poland Spring. We may be looking, but there’s someone looking right back.