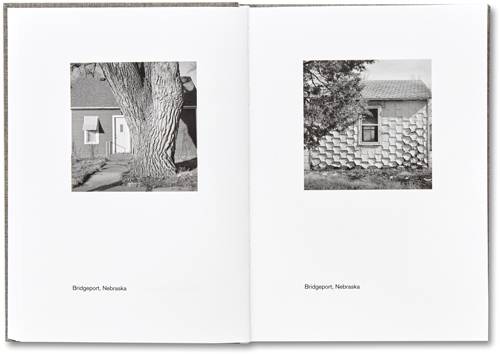

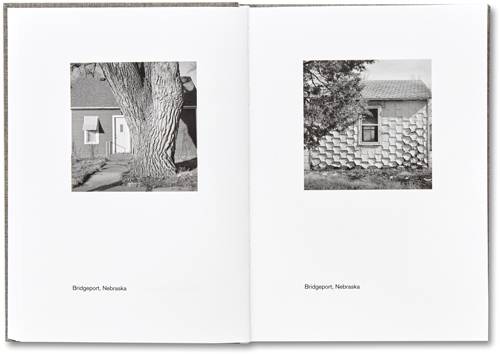

The idea of the romantic landscape was pretty much squashed by the New Topographics crew in the 1970s. Robert Adams, Lewis Baltz, Stephen Shore, and their contemporaries weren’t interested in the magnificent vistas that had inspired so much early photography, especially of the American West. Instead, they turned their attention to the industrial parks, tract homes, shopping malls, and other features of the built environment that, while a lot less picturesque, were a lot more ubiquitous. Their landscapes were matter-of-fact but hardly unsophisticated, combining dirty realism with a heady dose of the quotidian sublime. Their approach was not merely influential; it became a new way of seeing – one that informs several of the books under consideration here. Prime example: American Winter (MACK) by Gerry Johansson, a Swedish photographer in his 70s who, despite nine previous books, is new to me. But if his latest collection, a hefty block of a book with more than 300 small, black-and-white images and no text, had the impact of a new discovery, it’s far too solid to depend on the element of surprise. Made over the winters of 2017 and 2018 in rural and small-town Colorado, Nebraska, Wyoming, Kansas, and other states west of the Mississippi, the work is precise, restrained, and rigorously descriptive. There are no people on these roads, lawns, and empty lots, and Johansson isn’t particularly concerned with signs of their presence. Instead, he focuses on weathered wood siding, isolated buildings, bare trees, and the shadows caused by cold, raking light. Beauty is all the more poignant for being incidental and understated. There’s almost too much work here, but nothing feels superfluous; throughout, Johansson strikes a perfect balance of raw and refined.

Two other books share much of Johansson’s aesthetic – its concision, its scope – but are more obviously in debt to Alec Soth’s brilliant Broken Manual, his 2011 investigation of Americans living off the grid. Like that book, Kristine Potter’s Manifest (TBW) and Matthew Genitempo’s Jasper (Twin Palms) juxtapose landscapes and portraits to suggest a willful, rugged rootlessness – an escape (from civilization? from responsibility? from the law?) into a wilderness that’s at once welcoming and forbidding. Although both books have a large cast of characters (all white men, young and old), neither coalesces around a narrative. With a town in the Colorado mountains as her home base, Potter roamed the territory nearby; according to Stanley Wolukau-Wanambwa’s closing essay, she worked “at the intersection of myth, masculinity, and militarism,” although that last is far from explicit. Genitempo took his pictures in the Ozark Mountains of Arkansas and Missouri, where he found a similar cast of weathered loners; his photograph of one man’s cabin interior recalls Walker Evans’s sharecropper’s shack. There are echoes of Katy Grannan and Justine Kurland in both books – a sensitivity to masculinity in extremis and on guard paired with the recognition that many of these guys are not just solitary but lost to the world. Manifest and Jasper are handsome productions – beautifully shot, shrewdly sequenced, layered and mysterious. Potter and Genitempo aren’t spinning tales, they’re casting spells.

It’s not fair to Saul Fletcher’s self-titled new book (from Inventory Press) to squeeze it in at the end here, but it cannot be ignored. A collection of virtually everything he’s produced to date, the book is a testament to Fletcher’s stubborn, stunning originality. From the beginning (early images are dated 1997), bucking all contemporary trends, he’s worked small, at a modest, intimate scale that concentrates the intensity of the results. Photographing himself, his intimates, and charged, eccentric still life arrangements before paint-slathered studio walls, Fletcher often seems to be invoking and exorcizing demons, losing control and seizing it again – all with the furious vivacity and mordant humor of an outsider artist.