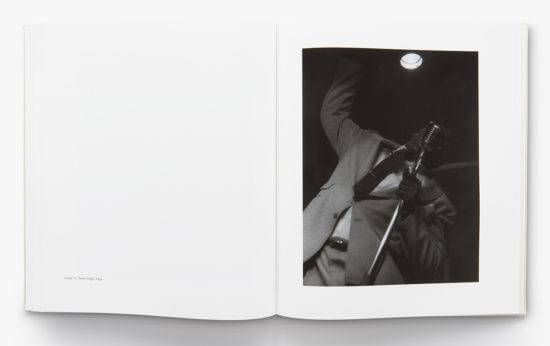

Just in time to contend for the best photo book of the year: Light Break by Roy DeCarava (First Print/David Zwirner). Following the reissue of The Sweet Flypaper of Life, DeCarava’s 1955 collaboration with Langston Hughes, and accompanied into print by a reissue of the sound i saw (2001), his brilliant “improvisation on a jazz theme,” Light Break is the first important survey of DeCarava’s work since the MoMA retrospective Peter Galassi organized in 1996, and it feels even more momentous. Trained as an artist, DeCarava tended to make his photographs compositions of dark and light, but it was darkness that he saw most clearly. The blacks in his photographs – in truth, as he pointed out, “infinite shades of gray” – are rich and subtle, with a velvety, smoky depth. And when his subjects are fellow African Americans, that enveloping darkness seems protective and comforting – not an alienating void but a familiar, welcoming place. DeCarava was a meticulous printer (he describes returning to one print again and again over a period of ten years before he was satisfied with the results), and the black-and-white reproductions here are superb – all the more important when so many of the book’s selections are new. Sherry Turner DeCarava, the art historian who is Roy’s widow, introduces this broader view of his work with an essay she wrote for a little-seen 1981 book. Although many of the photographs she discusses are, frustratingly, not included here, her sensitivity to the work opens it up, and her description of DeCarava’s approach is borne out by the pictures: “His outlook was always emotionally connected, truthful, energetic, and fascinating.” A picture of Romare Bearden at work finds the painter in shadow, but basking in the luminosity that seems to radiate from his canvas. I imagine DeCarava in the same position. He understood light as a medium of expression and darkness as a well of emotion. It’s tempting to overpraise his accomplishment, if only to make up for its relative neglect, but he deserves to be seen alongside Robert Frank, Harry Callahan, and Manuel Álvarez Bravo as one of the greats.

Top of the list for the best fashion photography book of the year: Tim Walker’s hefty, spectacular, utterly delirious Shoot for the Moon (Thames & Hudson). Walker, one of the most inventive and entertaining of the current crop of editorial photographers, veers between elegant extravagance and art-school anarchy: Cecil Beaton meets Tim Burton. Like those guys, he can be outrageous and gimmicky, but more often than not, he hits astonishing heights, and he’s never uninteresting. Casting about for inspiration, he channels Hieronymus Bosch, John Currin, Egon Schiele, and Lewis Carroll. At 300-plus pages, Moon is an overdose, but the fashion work (including out-takes) is especially knockout alongside Walker’s portraits of sitters from Bjork to Lord Snowden, some of whom resist being rendered as surrealist icons.

In a class by itself: François Halard’s A Visual Diary (Rizzoli). The Vogue interiors photographer’s best book so far opens and closes with scrapbook pages – collages of clippings, drawings, and scrawled notes that set us up for an ingratiatingly personal collection. Halard, whose own style is haute bohemian (views of his house in Arles, with its African masks amid Picasso lithographs, appear late in the book), has great taste and an eye for detail. That serves him well here, whether he’s wandering through Dries Van Noten’s gardens in Belgium or sizing up Eileen Gray’s Mediterranean villa. In between, he visits Louise Bourgeois, Andres Serrano, Marc Jacobs, and the late Saul Leiter’s poignantly empty East Village apartment. As portraits of the artists, in absentia, they’re all wonderfully intimate and revealing.

With PhotoWork: Forty Photographers on Process and Practice (Aperture), savvy gallerist-turned-private dealer Sasha Wolf has produced a book that’s as fascinating as it is instructive. All of the photographers respond to the same 12 questions about their approach to their work, from concept to style to final presentation, with intriguing side notes about their “First meaningful photobook,” “First meaningful exhibition,” and, occasionally, a “Personal fact.” (In Alec Soth’s case that fact is: “In high school, I had a job delivering Chinese food and discovered the thrill of peeking into a stranger’s home.”) In her Introduction, Wolf says she’s hoping the book “provides real-world guidance in an area that is not typically approached from the practical side: the creative process.” Her concise questions invite direct, specific answers but allow for revealingly personal takes on the issues at hand, especially when it comes to genre and editing. Dawoud Bey: “I let others worry about genres…. I only know two kinds of photographs: interesting ones and uninteresting ones.” Elinor Carucci is more blunt: “Fuck the genre.” Virtually everyone says editing is key to the success of any photographic project; they don’t all agree on exactly when it comes into play. “A body of work reveals itself over time,” says LaToya Ruby Frazier. Every dip into the book turns up something delicious. Justine Kurland quotes Valerie Solanis’s SCUM Manifesto. Robert Adams cites Flannery O’Connor. And, in answer to the question, “How do you know when a body of work is finished?” Gus Powell comes up with this: “When it is an object that can go out into the world on its own. When it is something that could end up being found at a thrift store. When I can’t remember it.” Note: The book’s understated design includes no illustrations.