Jim Goldberg has never been a traditional photographer, and certainly not, as a member of Magnum, a typical photojournalist. From the beginning, he’s given his subjects a voice, making them participants in his projects and inviting them to speak for themselves. The at-home portraits in Rich and Poor, 1985, are annotated in writing by the subjects themselves. The runaways and street kids in Raised by Wolves, 1995, scrawl comments throughout that book that add to the raw immediacy of the images and the diary-like text. Goldberg is so present in Wolves – so caught up in the struggles of these kids – that the reader wonders how he stays sane, but is never bothered by what seems like a total lack of objectivity. There’s no question of objectivity in his latest book, Coming and Going (MACK), a huge slab of densely collaged photographs and text that’s his most personal project so far. Loosely chronological, it’s a scrapbook autobiography in snapshots, screen shots, Polaroids, party pictures, notes, letters, drawings, and a lifetime of ephemera.

With very little captioned and less explained, the reader pieces a narrative together bit by bit. The words THE CANCER HAS SPREAD, written on four pictures of Goldberg’s mother, mark one turning point. But his father dies first – not before sending a letter reminding Jim of all the times he fucked up and ran away from home. Later, there’s a picture, mostly obscured, of his mother’s body in a cardboard box at the crematorium. The story is not without love and marriage. Goldberg’s first, in 1984, is summed up in four spreads; its end reduced to a handwritten text crammed on the picture of a burning truck at the side of a road in Italy. Portraits and memorabilia from Raised by Wolves and Goldberg’s ongoing work with refugees get carried along on the book’s headlong sprawl, folding into a rush of pictures of his daughter Ruby and his current companion, photographer Alessandra Sanguinetti. Everything is layered, fraught, and intensely felt, with almost no white space. If the style recalls Danny Lyon and Peter Beard and the content can’t help but remind us of Mitch Epstein and Larry Sultan (who was a close friend), Goldberg is fiercely original. His book’s cover and opening and closing spreads are so jammed with cut-up photos it’s alarming. Like spending a night with a speed freak – or an artist/autobiographer who doesn’t want to leave anything out. This reader wouldn’t have it any other way.

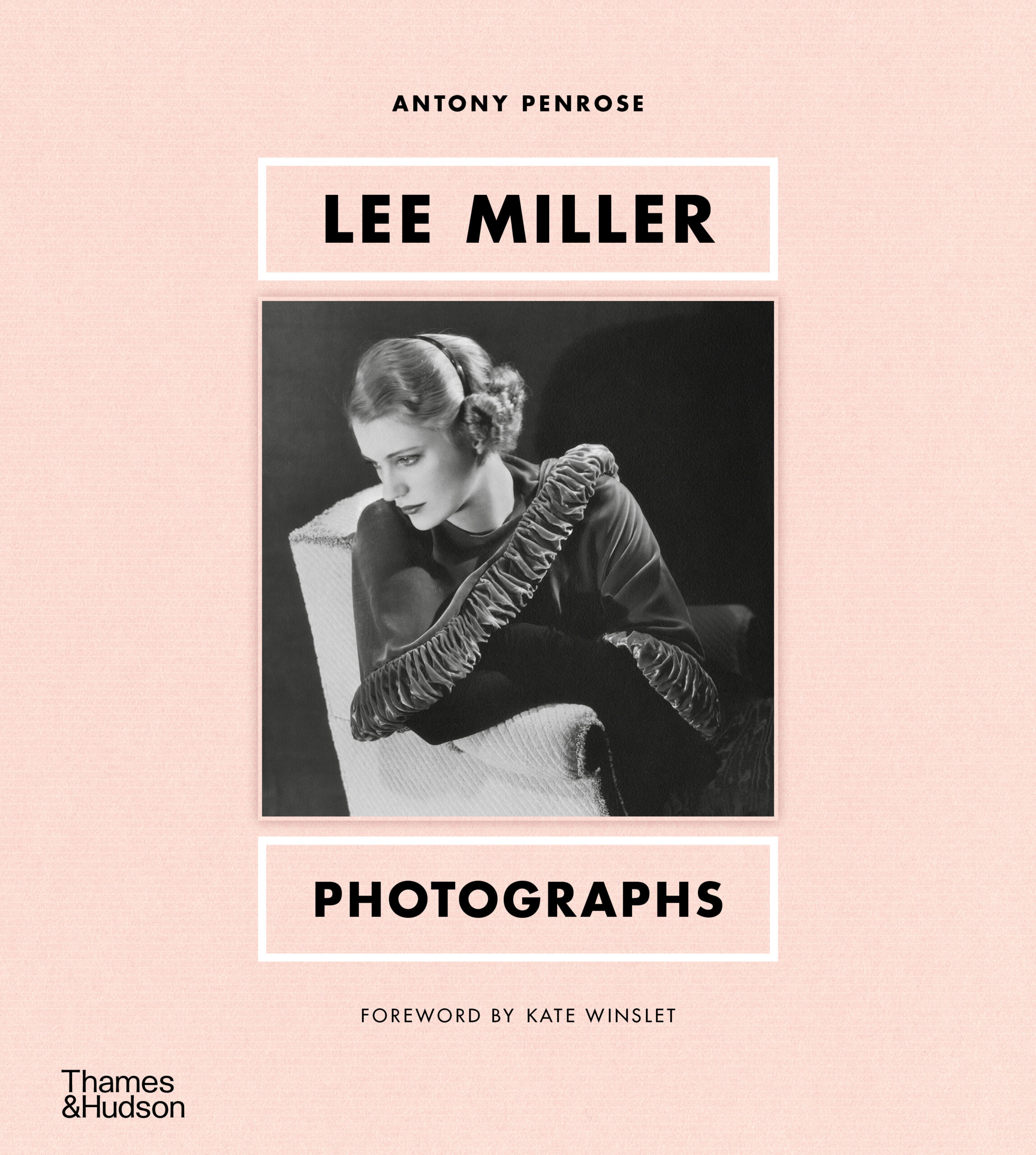

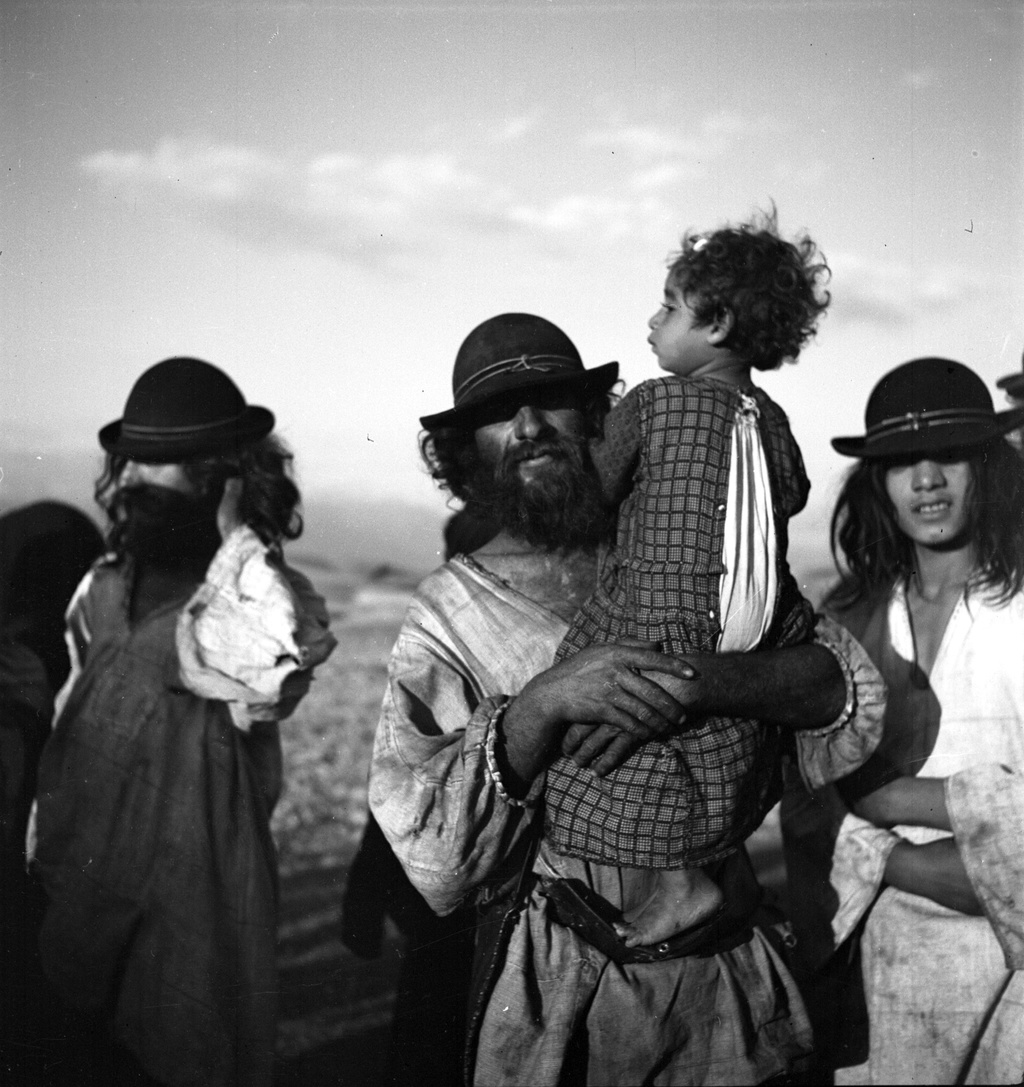

There are already a number of books collecting the work of Lee Miller and Daido Moriyama, but the latest ones are among the best. Lee Miller: Photographs (Thames & Hudson), edited and introduced by her son, Antony Penrose, leaves her history as a model and a muse to the text. Before Miller was photographed for Vogue, she was on its cover. Condé Nast, the magazine’s high-society publisher, had spotted her on the street and immediately arranged for Georges Lepape to draw her for the magazine’s March 15, 1927, issue. Man Ray made her even more iconic when he based one of his largest and most famous paintings, Observatory Time: The Lovers, on her full red lips, which he floated like a dirigible in a cloud-filled sky. But Miller insisted, “I would rather take a picture than be one,” and, early in the 1930s, she embarked on her own career in photography. Her first pictures weren’t just influenced by Surrealism, they summed it up brilliantly, capturing all its glamour and anxiety in images that are still unsettling. Working mainly in Paris before the war, she made memorable portraits of Picasso, Leonor Fini, Leonora Carrington, and Dora Maar. She spent the war years in London, where she got herself accredited by the US Army so she could travel freely and make some of her best work, of that shattered city and, later, behind the front in France. When British Vogue made her a staffer, she turned in fashion pictures but was much better known for her reportage, most famously of the living, the battered, and the piled-up dead at the newly liberated Dachau and Buchenwald. Penrose notes that Miller wasn’t in Germany for a news scoop; she was hoping to find friends who’d been taken by the Gestapo among the survivors in the camps. He doesn’t say if she found any. He also writes, “Perhaps the best training for being a war correspondent is to first be a surrealist, and recalibrate your perception of ‘normal’.” He has a point: In a crazy world, Miller was already adjusted, ready for anything.

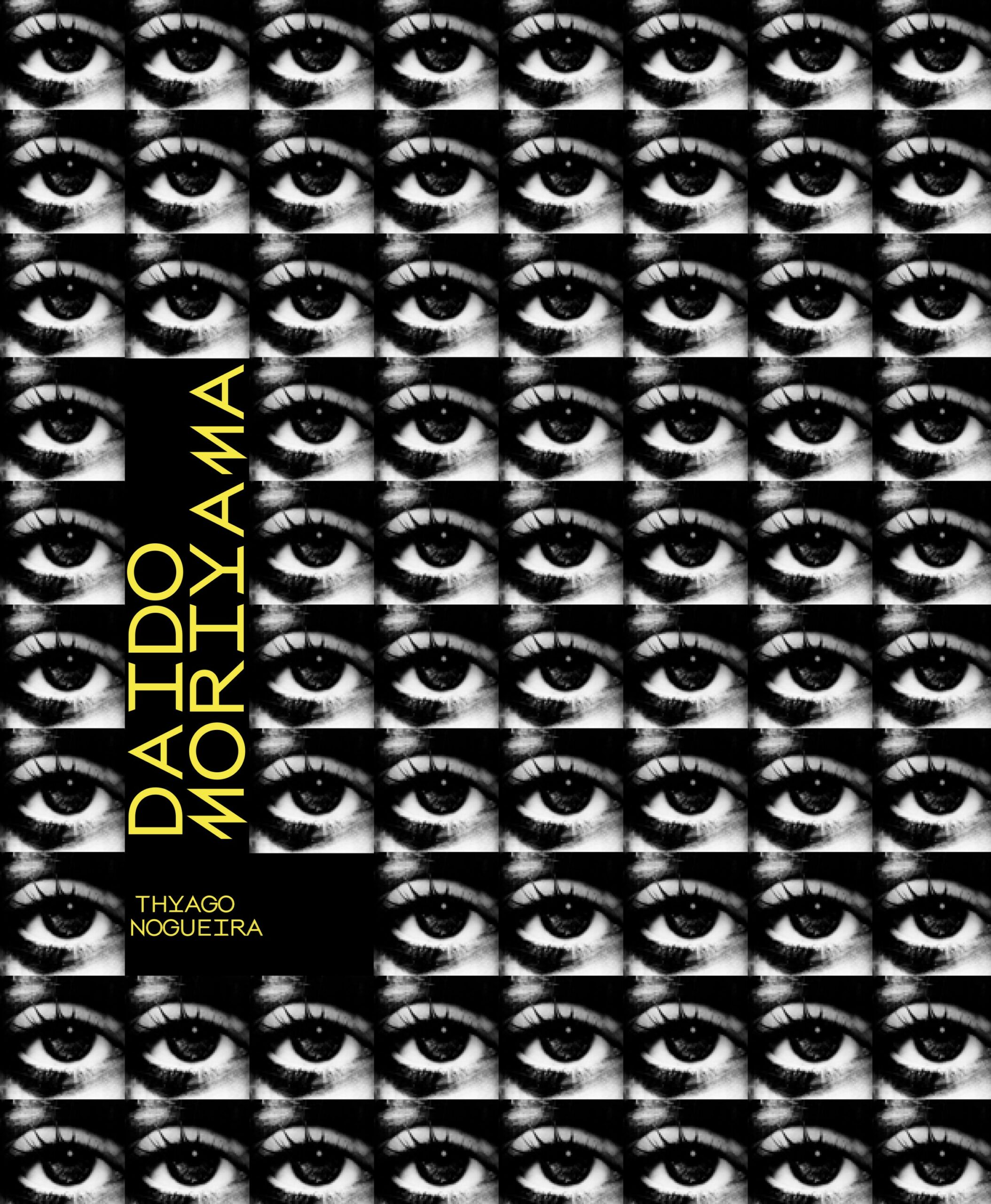

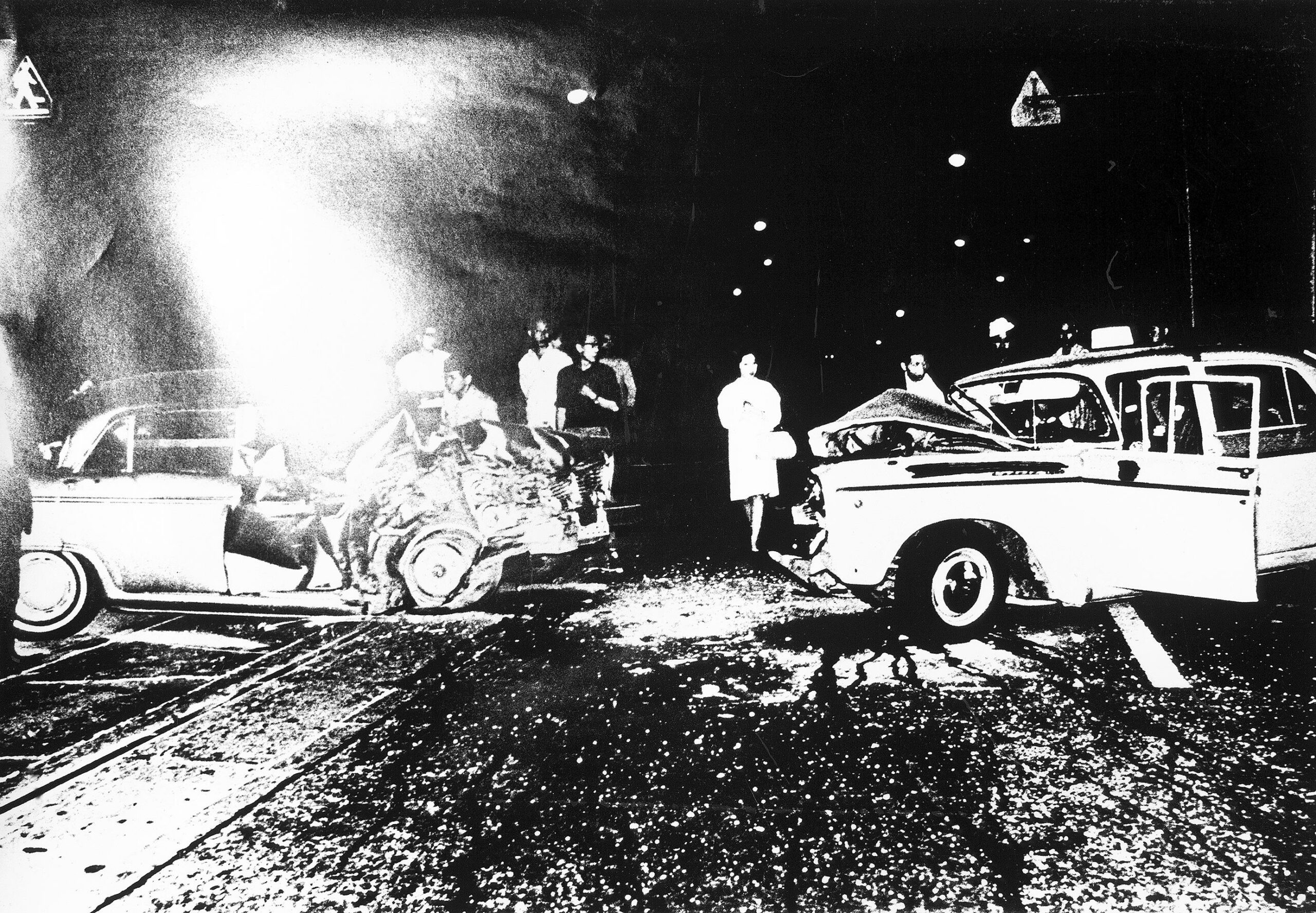

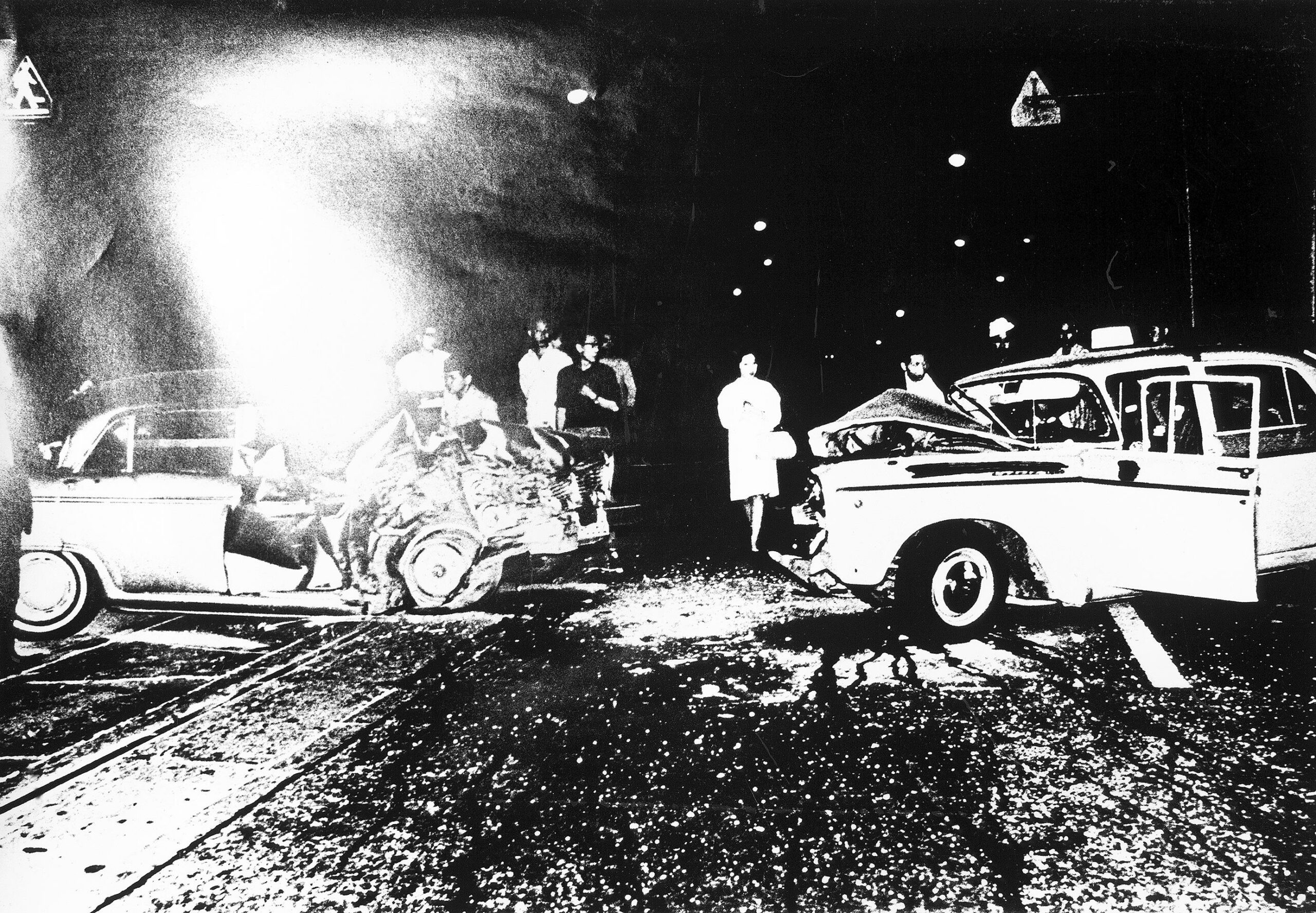

Daido Moriyama: A Retrospective (Prestel), shrewdly edited by Thyago Nogueira, is the catalogue to a traveling exhibition that originated in São Paulo this year. It has a lot of competition from countless previous Moriyama anthologies, but a sharp edge when it comes to design. Even before you open it, the book feels like a ticking bomb. With just under 200 images (more if you count the contact sheets), it’s packed and compact. A dense cover grid of a single staring eye opens up to another grid of a woman’s thickly painted lips, then: Bang! No title page, no introduction, just page after page of killer images. Grainy, insinuating, disintegrating, astonishing, appropriated – they channel Weegee through Warhol, with car-crash disasters and supermarket shelves stocked with the same dumb brand over and over. There are pictures of pictures, screen shots, and ads, milling crowds, wastelands – all in over-inked or blown-out black and white, save for two portfolios in lurid color. As the great photographer of postwar Japan, Moriyama is reliably dark and downbeat; his book unfolds like a kabuki film noir where even the passers-by are performers. At moments, this is hellish, but the work has the irresistible energy of a great punk record and is just as hard to get out of your head.