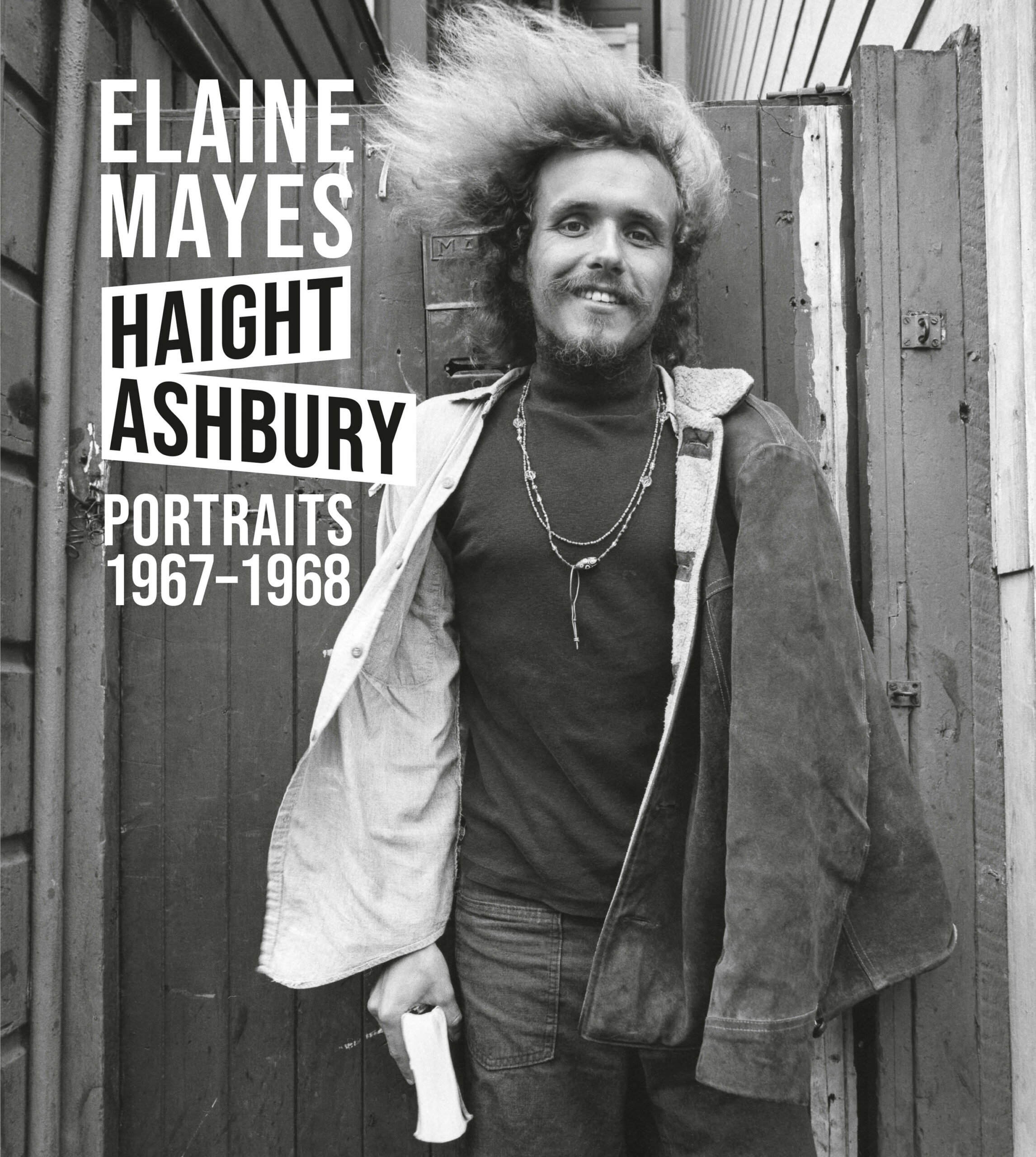

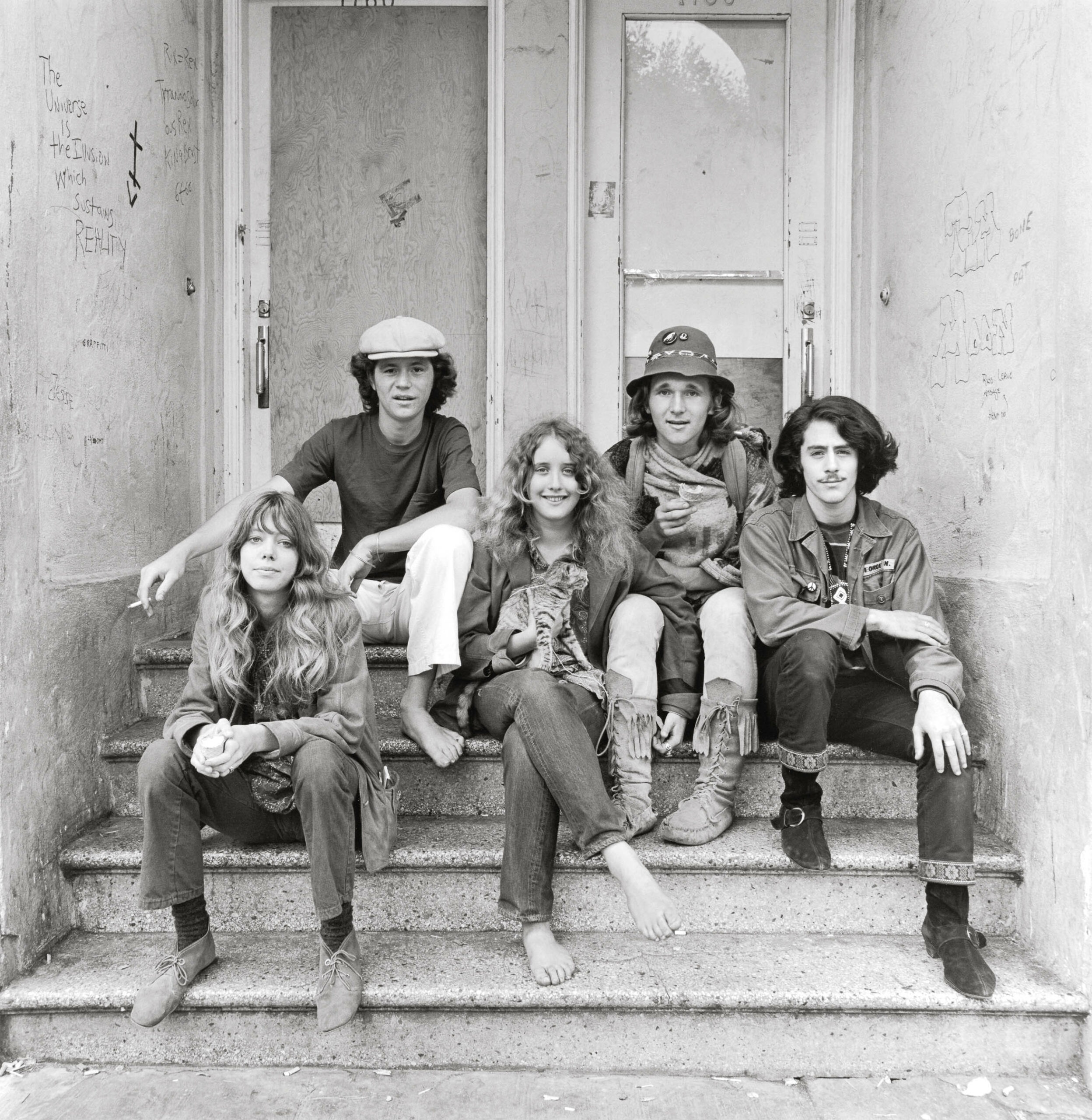

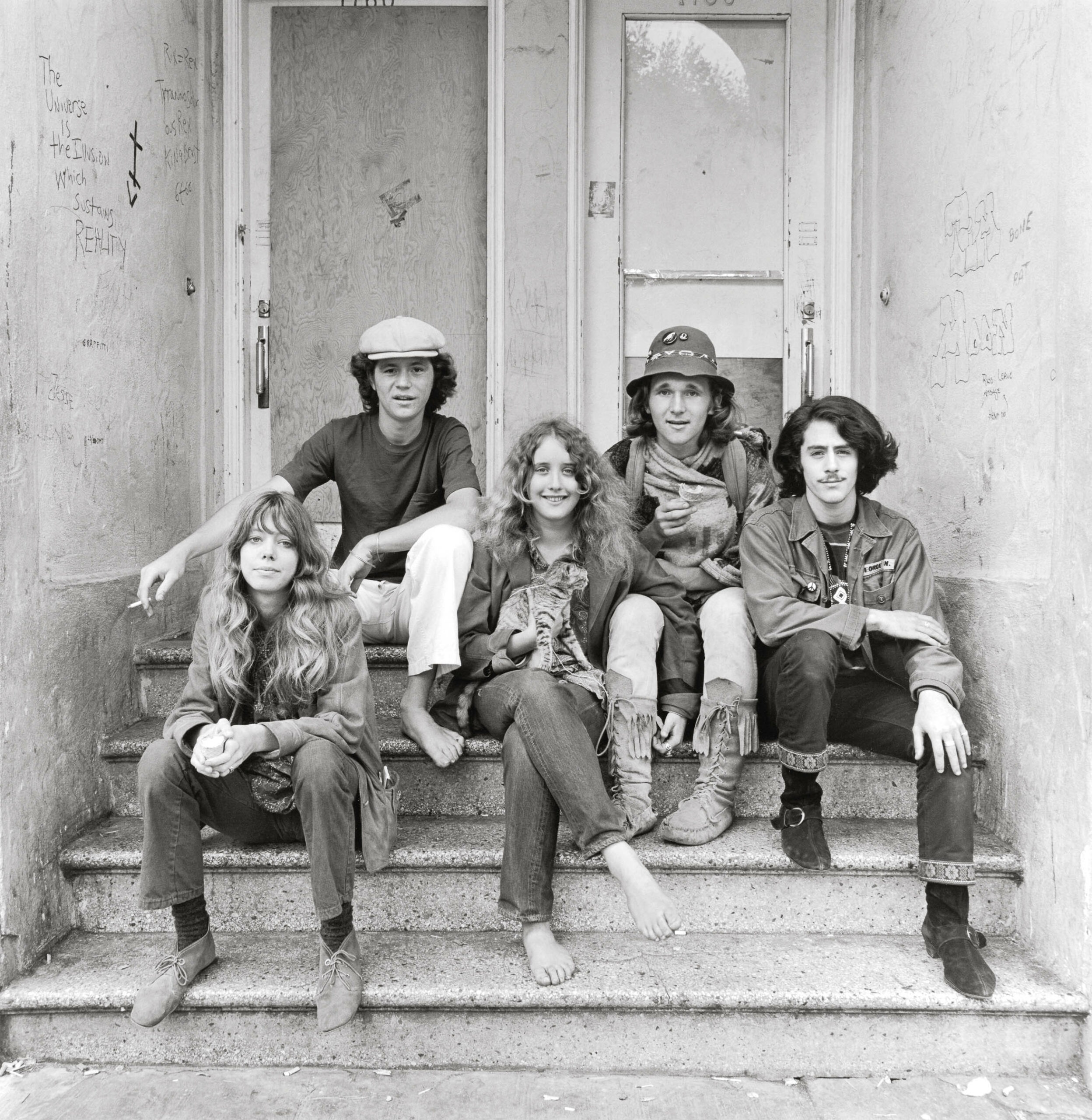

Haight Ashbury Portraits 1967-1968

“I was in my twenties in the 1960s. It was an exciting time, and I was attempting to grow up.” The opening lines of Elaine Mayes’s essay for her book Haight Ashbury Portraits 1967-1968 (Damiani) are disarmingly modest, if a bit misleading. (Born in Berkeley in 1936, she was in her thirties when this project began.) But there’s no question she was in the right place at the right time and could not have been more ready for the experience. Although she already had a career as a freelance editorial photographer, Mayes was at loose ends when she moved into a commune in the Haight in 1967 – the first of several shared spaces she’d live in over the next few months. She photographed her neighbors – introspective but easy-going, often barefoot – on the street and in their homes. Maybe because Mayes shared what writer and FotoFocus Cincinnati curator Kevin Moore, in his introduction here, calls their “sentiment of tentative idealism,” they’re open to her and, these many years later, hard to resist. Inevitably, perhaps, Mayes met Diane Arbus, on assignment in San Francisco for Esquire, got her stoned, and drove her around town. Arbus’s straightforward approach to (in)formal portraiture gave Mayes a path away from photojournalism, but the critical distance that Arbus maintained, and the darkness that seeps into her work, is absent here. It’s not a slight to call these great fashion photographs: Mayes enjoys every detail of her sitters’ hippie/boho looks, and that pleasure – along with genuine concern about where these kids are heading – suffuses the work.

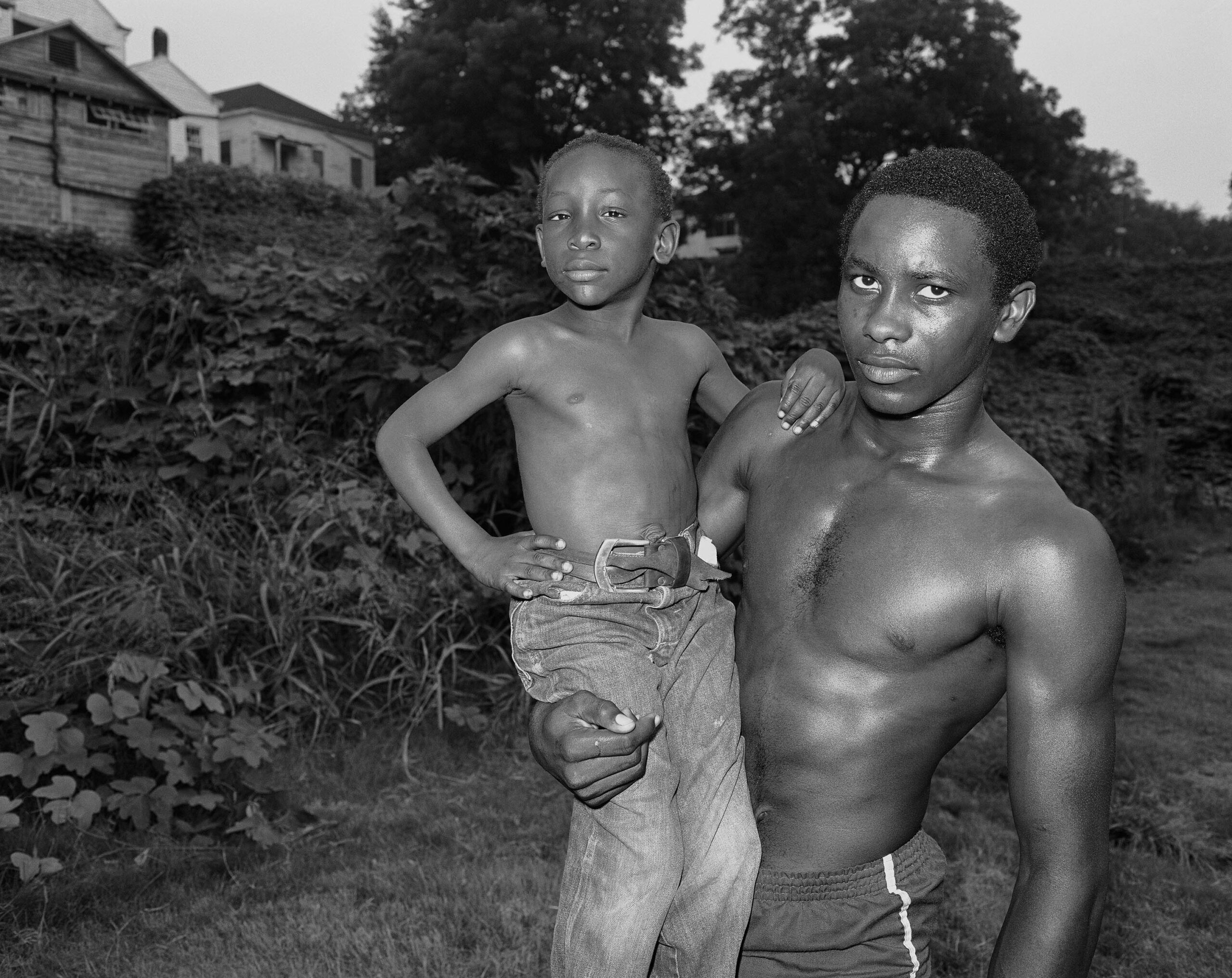

Baldwin Lee

Baldwin Lee, a Chinese-American photographer from New York, was in his thirties when he traveled through the South and made the 88 extraordinary pictures in his self-titled book (Hunters Point Press); they were culled, a note informs us, from an archive of more than ten thousand images. (Stop a minute to consider the achievement of the editor, photographer Barney Kulok, as sensitive as he is shrewd.) Lee had studied at MIT with Minor White and at Yale with Walker Evans (whose late-life teaching style he describes as “indifferent at best”). For a year, he also worked as Evans’s printer. Both photographers left an impression, Evans’s the most obvious, if only because Lee’s focus was also poverty in the rural South. In an interview here, Lee insists the work he made “would never have come about without adequate education and awareness: North/South, Black/white…poor/rich, powerful/subjugated, privileged/deprived, entitled/abandoned, hopeful/hopeless.” But Lee’s education would have been meaningless if he hadn’t been able to approach his subjects person to person and eye to eye. The warmth and soulfulness of his work is not the result of intellectual effort; it’s grounded in understanding, a combination of intensity and restraint, and, surely, a shared sense of otherness. Lee worked, in the classic manner, with a 4×5-in. view camera on a tripod and staged his photographs carefully, but he describes them as “flawed theater. No matter what I say, people do something else, and this is where it gets fantastically interesting” – an understatement where these pictures are concerned.

Sadly, Lee no longer takes photographs; he doesn’t even own a camera. He finds it difficult to engage with the world with any confidence, he says, and “I can no longer reconcile the difference between the lives lived by the people I photographed with the life I lived.”

Beautiful, Still

That is evidently not a problem for Colby Deal, whose first book, Beautiful, Still (Mack), finds him so casually intimate with his subjects that it feels like a family scrapbook. In some sense, it is just that: many of the people in Deal’s photographs are extended family in Houston’s largely Black Third Ward. The result is an intricate and intimate sense of community – a view that could only come from deep inside. Although the Third Ward is increasingly threatened by gentrification and displacement, its vitality drives Deal’s work and give it a presence that’s all the more powerful for being so steeped in history. But Deal also sees the other side: a haunting sense of unease and evanescence. For a photographer who works, like Lee, with a 4×5-in. view camera, his pictures can be surprisingly ephemeral – blurred, hazy, as if made in passing. Many of them feel like snapshots, which suits the emotional nature of the project. Deal’s pictures – of backyard barbeques, family reunions, fast-food joints, and boarded-up homes – already look like they’ve been saved from oblivion. Maybe the anxiety of preserving it all undermined the editing process, but it’s hard to complain about too much fine work. Flaws and all, this is one of the year’s best and most original books.

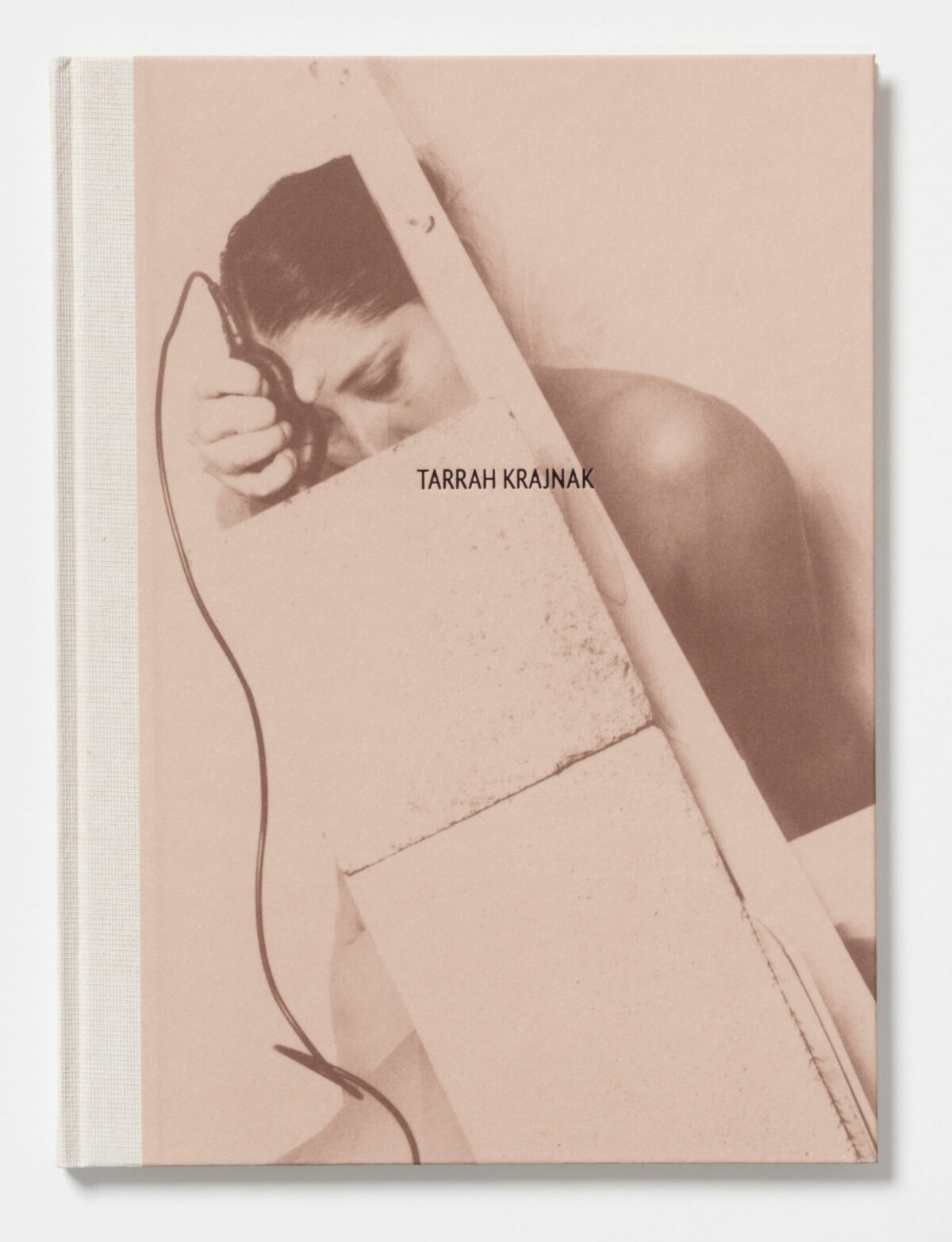

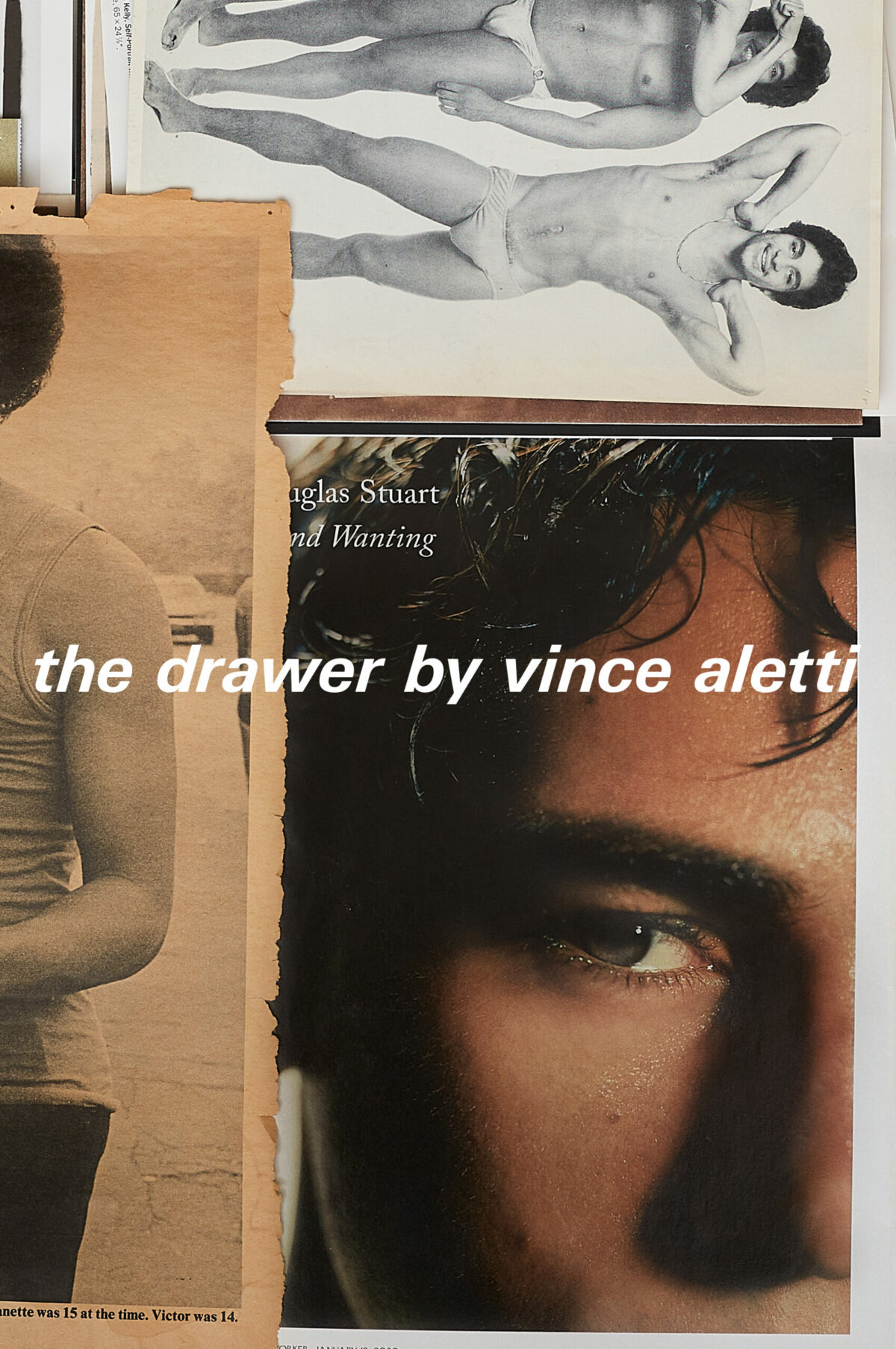

Vince Aletti, formerly a photography critic at the Village Voice and the New Yorker, reviews photography exhibitions and books for the New Yorker’s online Photo Booth feature. His book, Issues: A History of Photography in Fashion Magazines, was published by Phaidon in 2019. The Drawer, a picture book, will come out later this fall from Self Publish, Be Happy, distributed by D.A.P.