Los Angeles artist Matthew Brandt is known for using an experimental process that incorporates something of the subject in the development of the photograph, such as sweat for portraits or lake water from lakes in a landscape. When he found out he’d be doing a show in Atlanta, at Jackson Fine Art through July 1, he began thinking about a fitting subject and process. He admits that he began his series 1864 with a naive understanding of Atlanta, mostly informed by Gone with the Wind and Georgia’s nickname, “the Peach State.” As a result, this show consists of still lifes of peaches and large-scale works based on George N. Barnard’s 19th-century albumen-silver prints of Atlanta in the aftermath of General William T. Sherman’s scorched-earth policy, enacted in his famous march across the state during the Civil War.

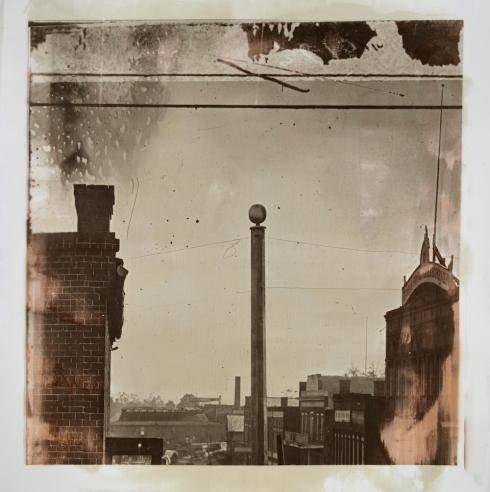

Brandt also used albumen prints, an appropriately historic process traditionally made using egg whites and silver nitrate. To create the photosensitive strata, Brandt whipped up a concoction using silver nitrate and the ingredients of a peach pie — peaches, eggs, salt, sugar, flour, cinnamon, butter. Using digital files of Barnard’s images, Brandt cropped them to draw attention to the sky. In one photo, for example, a demolished railroad depot sits in a crumpled heap in the foreground; in another, the sky dominates the tops of buildings visible along the bottom edge. People are nowhere to be found in Brandt’s versions, a choice that, for better or worse, thwarts the viewer’s empathy, keeping the focus on the formal qualities.

Brandt says he focused on the skies because that’s where flaws — scratches, fingerprints, and other marks — are most visible. Barnard had to travel with a portable darkroom to process the photographs in the battlefield and its aftermath, and Brandt was attracted to evidence of the photographer’s hand as well as the notion of the constancy of the sky, linking the present with the past.

The still-lifes of Styrofoam peaches that have been cut into portions and arranged in shifting geometries, while lovely, fail to escape cliché. His use of Styrofoam models rather than the actual fruit is also puzzling, given his use of peaches, eggs, and other pie ingredients for the albumen prints. There may be something to be said about the artificial fruit and the artifice of history, but it remains unstated.

There’s a lot to unearth in Atlanta’s rich history, including the very reason for the Civil War: slavery. Brandt scratches the surface in images that please but don’t satiate.