The ubiquity of digital imagery and the profound changes wrought by the Internet and social media are underlying themes of the International Center of Photography’s broad and thought-provoking triennial, A Different Kind of Order. But the 28 artists included in the show, on view through September 8, have responded to this shift in inventive, often unpredictable ways. Some, born in the 1980s or later, never experienced a shift at all, having grown up immersed in digital media.

One gratifying aspect of the show is the perseverance of the handcrafted, unique object. Elliott Hundley’s Pentheus, based on Euripides’s The Bacchae, is a wall-sized three-dimensional collage. The underlying image is covered with bits of type, cut-out figures from Hundley’s own photographs, and found images and objects, attached to the work with long pins. Small magnifying glasses positioned throughout the piece enlarge certain of the photographic fragments. Astonishing in its detail and complexity, the work explores tragedy, storytelling, and consumer culture.

Other pieces in the show also engage in some form of collage, a practice that is both well established and suited to the moment’s multiplicity of images. Japanese photographer Sohei Nishino assembled maps of city neighborhoods that look at first glance like off-kilter Google street views. Rather, the works are made up of individual photographs that Nishino took as he wandered the streets, block by block, then painstakingly reassembled. They are impressionistic renderings of a place, which makes them among the many works in the show to question the reality represented in a photograph.

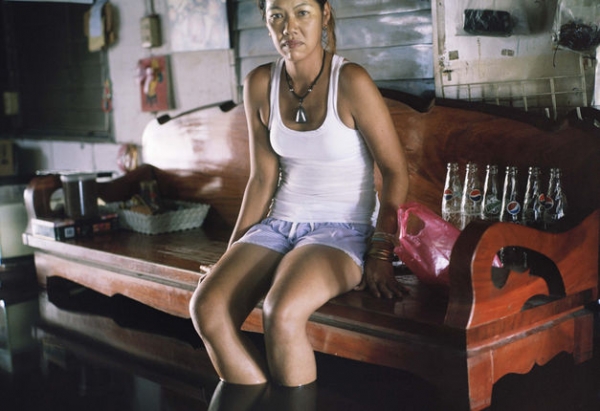

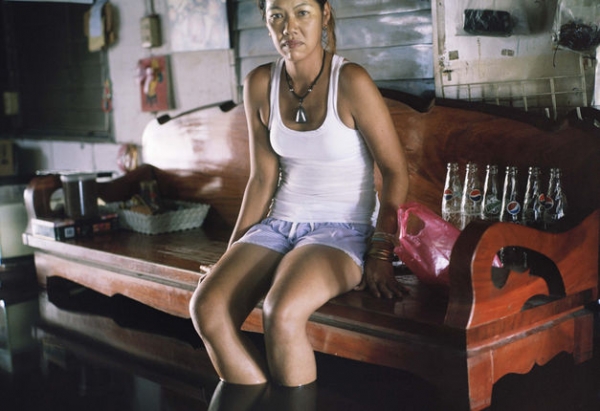

The reality presented by the mass media, in particular, is addressed by a number of artists, including Gideon Mendel, whose beautiful, somber color photographs depict the increasing incidence of flooding around the world. Mendel goes to places – Haiti, Thailand, Nigeria – weeks after the storms have left, to find that the waters haven’t gone down, help is not on the way, and nobody is reporting it. The people, by necessity, are going about their business, cooking, opening their stores, wading through water than is sometimes chest high.

And then there is Thomas Hirschhorn’s video, Touching Reality, compiled of shockingly graphic images of violence around the world that would not be printed in the mainstream media. The video show the images scrolling by on an iPad, pushed across the screen by a manicured female hand, suggesting a viewer far removed from the violence depicted. The piece is excruciatingly difficult to watch, which is of course the point. Are these images edifying or obscene? The triennial is powerful precisely because the curators have chosen artists who ask such difficult questions.