Many of us have been waiting for a major exhibition of the work of An-My Lê. Now, two have arrived, one following on the heels of the other, albeit on different continents. Beginning March 14, the Carnegie Museum of Art in Pittsburgh is presenting On Contested Terrain, the artist’s first major survey show, with nearly 125 images. Silent General, which closed February 29 at the London branch of the Marian Goodman Gallery, took its title from Lê’s hugely ambitious recent project (2015- ), but also included some older images. The straddling of places and times seems fitting. Lê’s work always seems to involve spatial and temporal slippages. The now contains then; the here contains multiple elsewheres.

Picking through my archive (it’s not that romantic – just a folder on a hard drive), I find I first wrote about Lê’s images back in 2006. I was trying to consider a new relationship that was emerging between documentary practices and the contexts of art. A number of photographers were using the camera’s soberly descriptive powers (let’s call it “straight photography”) to record places and events that were much less straightforward. One approach was what I had called “late photography” – the making of images in places where notable events had happened in the past, spaces of ruin and aftermath, charged with haunted memory. Simon Norfolk and Paul Seawright had not long before made their subdued images of the remnants of multiple wars in Afghanistan. Sophie Ristelhueber’s photographs of the war-torn deserts of Kuwait (Fait, 1992), not widely appreciated when first shown, were growing in stature and influence. Another approach was a kind of photograph that pointed forward in time, showing people and places in states of preparation or rehearsal for events to come. Sarah Pickering was photographing police riot-training facilities and fire-department test sites. Adam Broomberg and Oliver Chanarin documented a fake Palestinian town the Israeli army built in order to practice its future tactics of urban warfare.

These were straight images of a crooked world. It was a kind of photography in which time was layered and space – of the image and the subject matter – was both real and unreal. Its challenge to photographic representation lay less in the medium than in the increasingly deceptive surfaces of the contemporary world in front of the lens. This was not the testy and suspicious questioning of the photograph as document that had emerged from conceptual art in the 1960s and ‘70s. Peace had been made with the medium’s powers of description. It was life itself, appearance itself, that demanded closer scrutiny. What was required of photography was an honest recording of worldly deception.

More often than not, the photography was cool, slow and formal, shot on larger formats and presented as disturbingly elegant tableaux. The direct documentation of “hot” events, through images formed by the arresting effect of the quick shutter, had been sidestepped. Exposures were longer, focus was deeper, and grain – once the guarantee of authentic reportage – was replaced by endless, seamless detail. It was a kind of photographic mode the 19th century would have recognized, were it not for the mixed-up society it was describing.

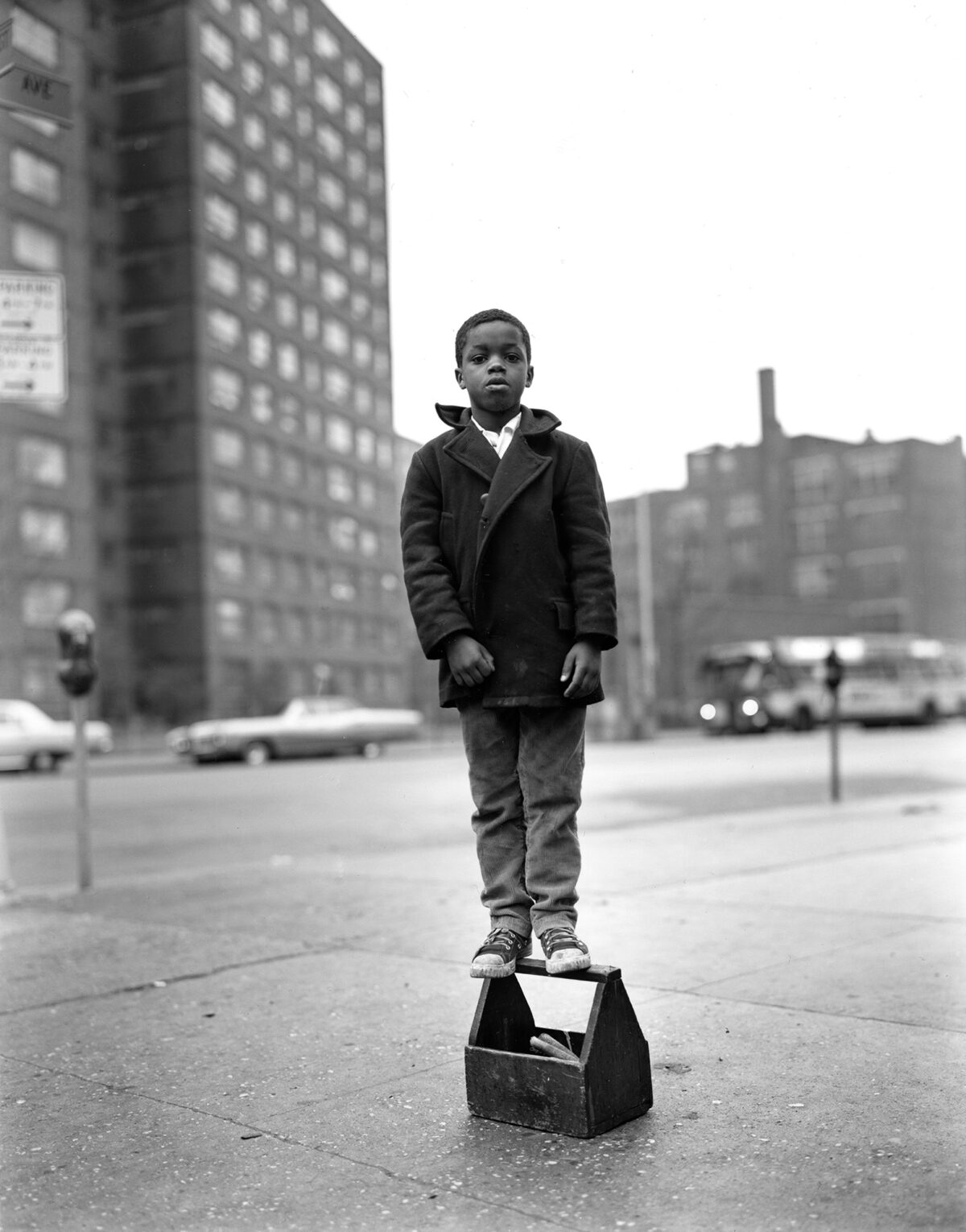

As far as I was concerned, the real key to understanding this shift (which has turned out to be long-lasting) was the work of An-My Lê. She had arrived in the United States in 1975, aged 15, as a political refugee from Saigon, Vietnam. Later she studied in the MFA program at Yale and committed herself to photography. Between 1994 and 1998 she returned several times to Vietnam, making images informed by her years of absence, by the strains of history, and by the imaginary “Vietnam” constructed by the North American culture to which she had grown accustomed. In 1999 she began to photograph Vietnam war reenactment groups in Virginia. Both projects were direct encounters with places and people, yet they were also indirect, filtered allegorically through the inevitable gauze of memory, fantasy, and ideology.

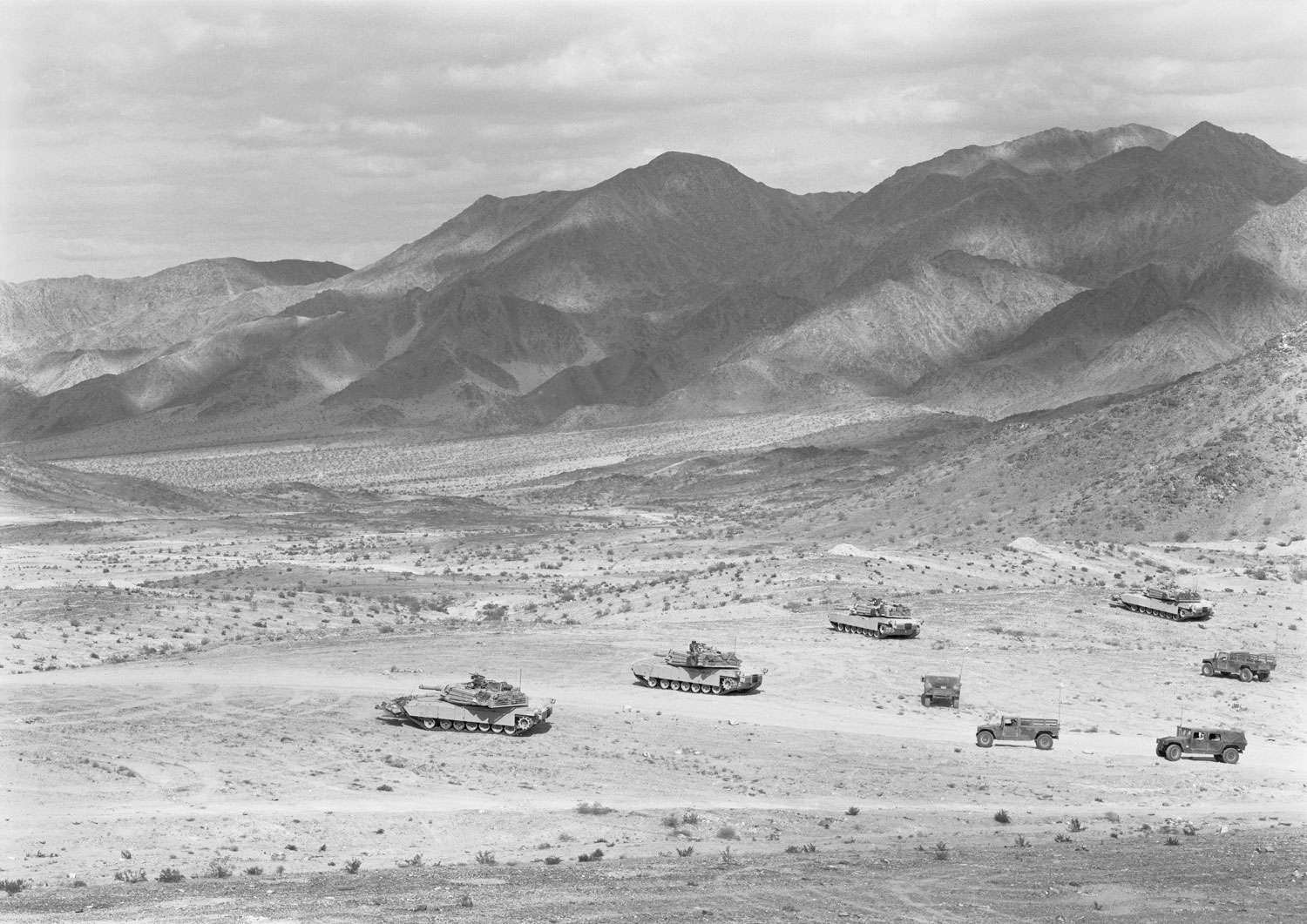

In 2005 Lê published the important book Small Wars. It brought together three related series. Viêt Nam comprised a selection of the images made on those return trips to her country of birth; Small Wars was a suite of war reenactments; and 29 Palms showed the U.S. military practicing in the California desert for combat in the Gulf. All the images were as formally and technically assured as they were conceptually complex. With rich mid-greys, the sumptuous prints seemed to extend the legacy of classic landscape photography that is still venerated in North America. There were clear echoes of the work of Robert Adams, for example. At the same time, Lê was in circumspect dialogue with a world whose surfaces were becoming increasingly difficult to decipher.

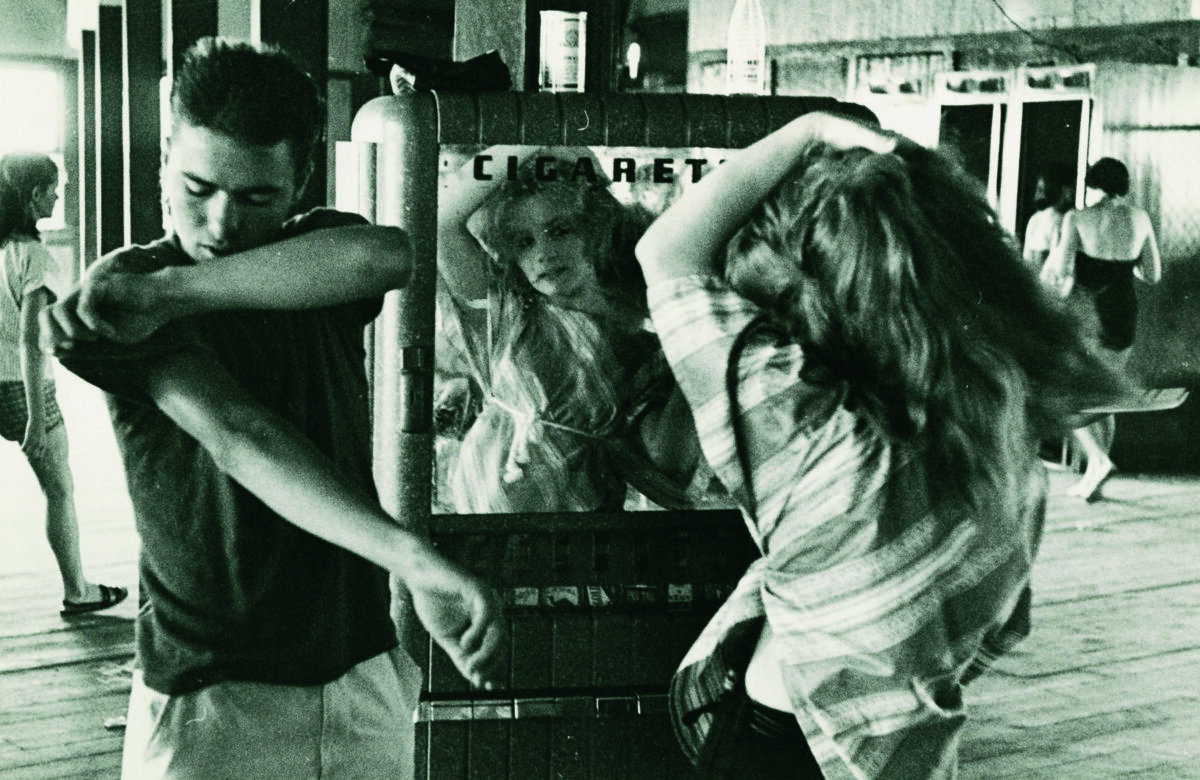

To all who saw that work, either on the page or the wall, it was obvious An-My Lê was in it for the long run. It is not uncommon for a photographic artist to establish a set of themes and visual strategies that are rich enough to be unpacked and explored over a long period of time. In the years since that trilogy, Lê’s epic, multi-part projects have extended in several directions but always circling around that nexus of history, ideology, conflict, and landscape. For many years she worked on what became Events Ashore, tracking the non-combat activities among the personnel of U.S. military ships as they moved around the globe. For those on board, a ship is home but it is transient, following paths determined by the past and present dynamics of foreign policy, just as the U.S. had been responsible for the artist’s own displacement.

Lê’s latest work, Silent General, is her most politically urgent to date, but it is no less elliptical for that. The serial photography of past projects has given way to something more fragmentary. Myriad scenes and situations are brought together. We see statues of secessionist generals Robert E. Lee and P.G.T. Beauregard that have been removed and placed in Homeland Security Storage, following a call to take down memorials related to the Confederacy. There’s an image of a fake Oval Office, surrounded by lights and staff on the set of Saturday Night Live’s ongoing parody of the Trump era (or the parody that is the Trump era). A family sits by the water under the Presidio-Ojinaga-International Bridge, along the border between Texas and Mexico. High school students protest gun violence in Washington Square Park in New York City. There are photographs of historical battle scenes being filmed by large casts and crews in the landscapes of Louisiana. Migrant workers are harvesting asparagus in Mendota, California. Lê’s visual attention is, as always, acute and generous, giving the viewer much to look at and interpret. And again, the classical poise of each knowingly “beautiful” composition is undercut by the troubling content. Moving from one image to the next, retracing Lê’s own nationwide road trip, is an invitation to consider the unspoken resonances. All these pictures connect, in that sublimely terrifying, internet-aided way in which we intuit that all the ills of the world are connected. Each image is a symptom of the U.S.’s present divisions, denials, and distortions. Each is a product of crimes and betrayals almost forgotten or erased. What interests An-My Lê are the very high stakes of that forgetting and erasure, and the need to attend to their traces. Looking the crooked world straight in the eye is her way of doing it.