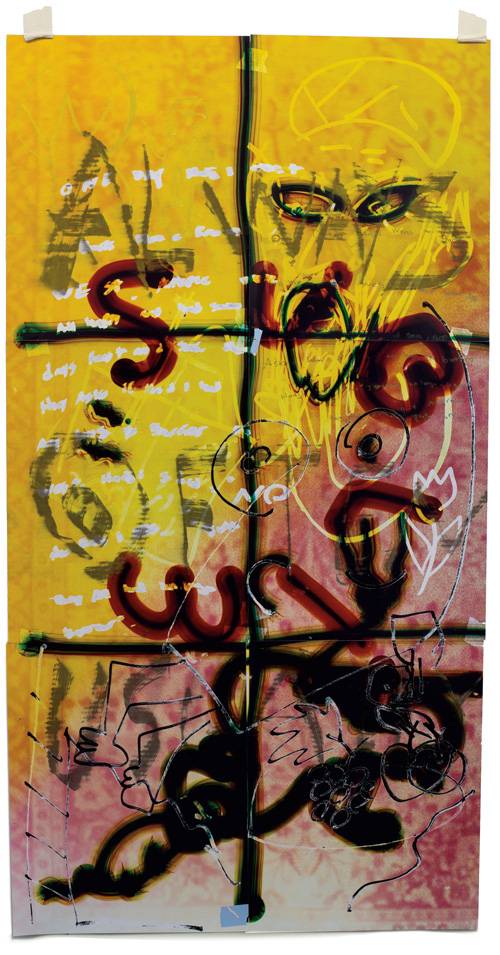

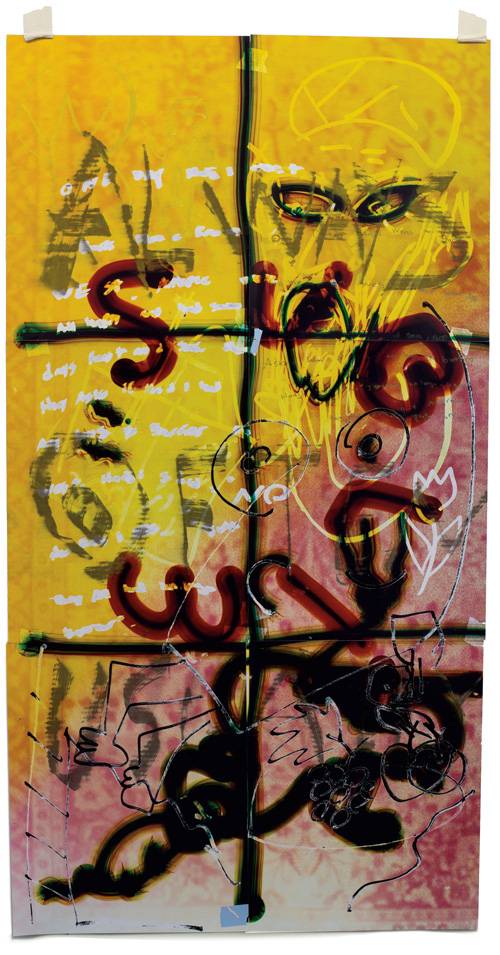

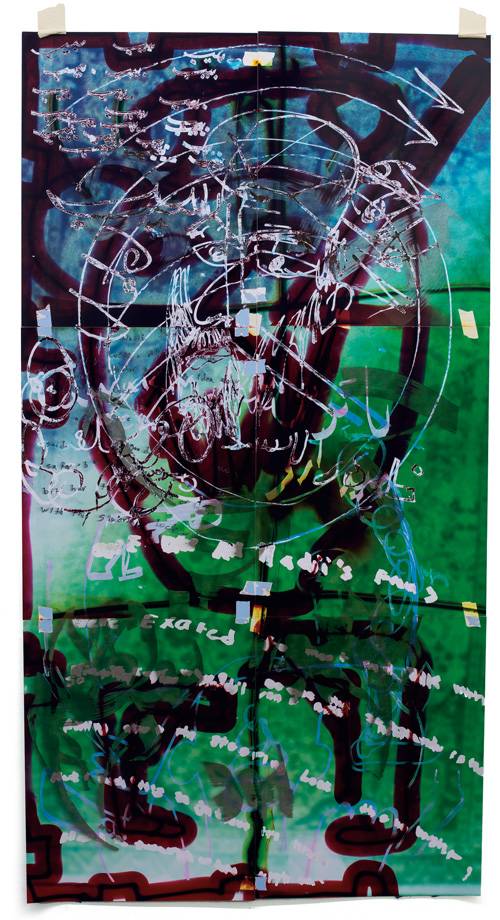

Iranian artist Hadi Fallahpisheh brings a complex layering of conceptual content to his abstract, experimental photographs. With their gestural swaths of bright color and scrawled graffiti-like texts, his camera-less photograms read like contemporary paintings with a raucous surface, but they also mimic prayer rugs. They are the same size as formal prayer rugs, 60 x 32 inches, and their base layer is a projected pattern appropriated from examples of prayer rugs that Fallahpisheh found on the internet. The texts that the artist scribbles across the image’s surface also tell a joke, the butt of which is a simpleminded fictional character named Hadji whose nonsensical sayings and actions portray him as a fool.

Hadji, of course, is close to the artist’s own name, Hadi. It is also the word used to refer respectfully to a Muslim elder – it derives from the name used for people who have successfully made the pilgrimage to Mecca (Hajj). And it has come to be used pejoratively, according to the artist, by people referring to Iraqis, Arabs, Afghanis, or Middle Eastern people in general. That the joke is on Hadji is part of the artist’s critical comment on the assumptions made about Middle Eastern cultural identity. He subverts exoticization by lodging a nonsensical, earthy buffoon in the middle of the work, owning a crude stereotype in order to embed the illogic of absurdity. Coming from Tehran to the U.S. in 2014, Fallahpisheh studied at the International Center of Photography and has just completed his MFA at Bard. He recently showed his prayer rug photograms in Berlin at GNYP Gallery.

In earlier photographs of urban situations, he created edgy fictions with noirish narrative texts. His photograms were a sudden departure into a kind of darkroom performance and painterly abstraction. After taping together six smaller pieces of photo paper to constitute the large-scale image, he moves around the composition to write the Hadji texts, wielding a marker and a flashlight to inscribe gestural marks, all in the short time needed to make the exposure. The texts are sometimes legible, sometimes not; they include misspellings, and some words feel “lost in translation,” but they appear clearly in the checklist as titles, such as these:

Sublime One day Hadji went back home from the west, people partied and danced for one week, then asked if Hadji had any language barrier in the west? Hadji thought for couple of minutes and said: “No, I was fine and had no problem, but they all had language barrier.” Then people laughed.

Turning Wheel Lock One day Hadji bought a Steering Wheel Lock for his car. All the people gathered together and excitedly asked what is Hadji’s idea about this new product? Hadji thought for a couple of minutes, and said: “It’s a very good product, I really like it and feel much safer, but honestly it’s a little bit hard to turn right or left while driving with this product.” Then every one laughed.

Although acknowledging the influence of painters like Basquiat and Cy Twombly (and the joke paintings of Richard Prince), Fallahpisheh says his sense of abstraction resides more in content than form, pointing to the metaphorical parable found in a 13th-century poem by Rumi, “The Elephant in the Dark,” which tells how different men, led into a dark room to touch an elephant, draw different conclusions about their encounter based on their limited individual perspectives. The telling abstraction in his work is the use of irony in creating a character like Hadji.