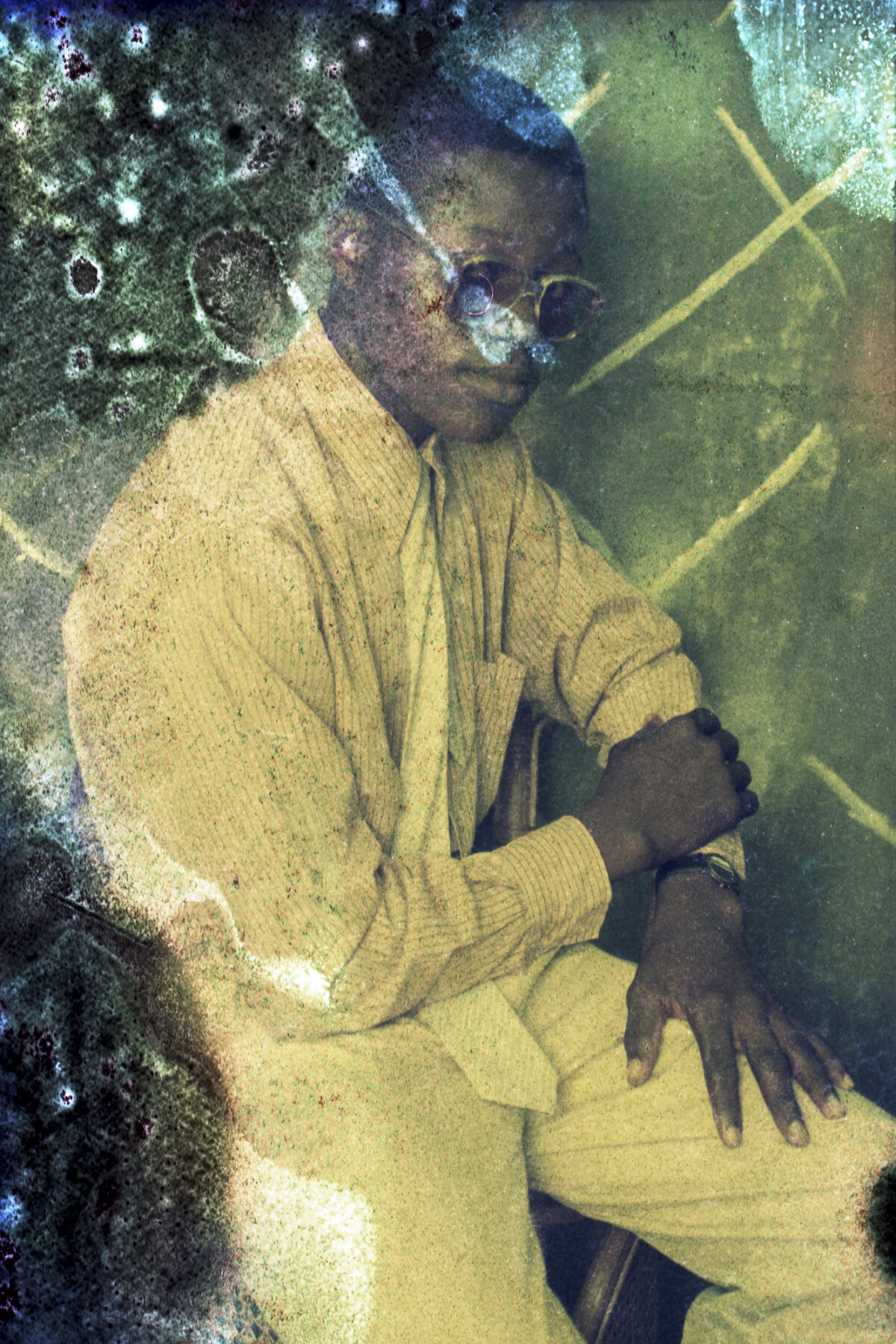

This past February, looters in Bangui, in the Central African Republic, destroyed the photography studio of Samuel Fosso, dumping negatives and prints into the street. Associated Press photographer Jerome Delay and photojournalist Marcus Bleasdale happened to notice the work scattered in the road and rescued as much of it as they could. The exhibition of Fosso’s photographs at the Walther Collection through January 17 underscores what a loss it would be if that work had been destroyed. Fosso, who was born in Cameroon, opened a photography studio in Bangui when he was all of 13-years-old. More than a dozen small vintage studio portraits are on view in the Walther Collection’s library, mounted on cardboard and displayed on bookshelves. From a photograph of a couple embracing to one of two small, smartly dressed children gazing solemnly at the camera to a young man striking a kung fu pose, they suggest a trusted photographer who enabled his subjects to perform their ideal selves for the camera. The photographs are stylish and playfully empowering.

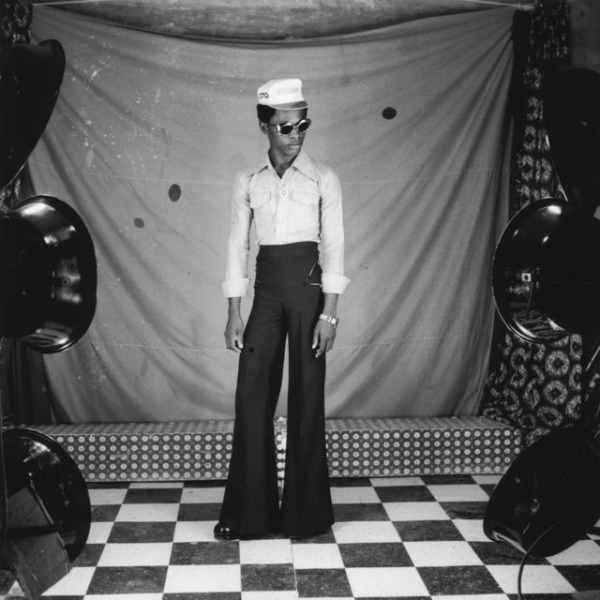

Those same elements inform Fosso’s self-portraits, which invite comparisons with studio photographers Seydou Keita and Malick Sidibé, but also with the performative self-portraits of Yasumasa Morimura, Cindy Sherman, or the Nigerian-born Ike Ude. Fosso’s black-and-white self-portraits from the 1970s show him adopting various incarnations of cool, wearing bell bottoms, a Kodak cap, and sunglasses, or, in an image that looks ahead to his African Spirits series from the late 2000s, wearing a t-shirt with the faces of Barthélemy Boganda, the first prime minister of the Central African Republic, and Jean-Bédel Bokassa, military ruler of CAR, slyly introducing iconic imagery of political figures into his work. In African Spirits (2008), Fosso recreates well-known images of Malcolm X, Angela Davis, Muhammad Ali, Kwame Nkrumah, the first president of Ghana, and others, reflecting on style versus substance and the way such images shape the public imagination.

Similar themes underscore the vibrant color photographs commissioned by the Paris department store Magasins Tati in 1997. The sharp political commentary (about class, race, and colonialism) is couched in opulent imagery. In one, he embodies a natty golfer surrounded by plastic potted plants – smartly dressed but full of fakery — in another (titled Le chef qui a vendu l’Afrique aux colons), a bejeweled, self-satisfied chief in animal skins and white plastic sunglasses. The backdrop is hung with African textiles, which feature a repeating motif of hand-held mirrors, suggesting the chief look hard at himself.