At Vielmetter Los Angeles, five contemporary artists created new works or reconsidered their archives with the impact of photographer Kwame Brathwaite in mind. The subject of an overdue touring retrospective, Black Is Beautiful: The Photography of Kwame Brathwaite, which premiered at L.A.’s Skirball Cultural Center in 2019, Brathwaite was a prominent figure in the second Harlem Renaissance. Through his photographs and his work as an organizer, he is largely credited with helping popularize the “Black is Beautiful” political slogan and the corresponding movement that coalesced in August 1963, with the protest of Wigs Parisian, a white-owned beauty-supply store in Harlem.

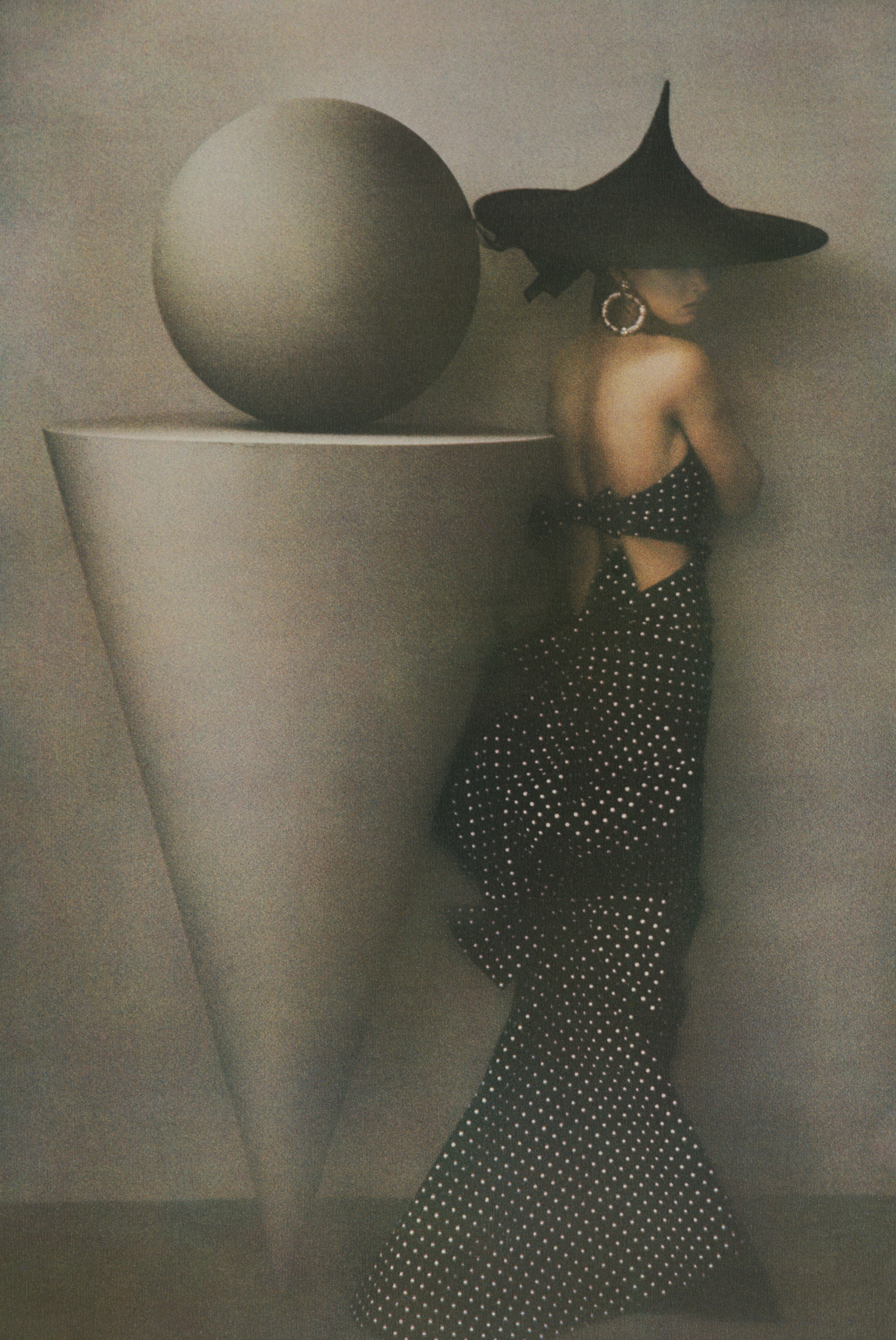

The exhibition featured five striking portraits made by Brathwaite in the 1960s and ’70s, including one of his wife, Sikolo, wearing an intricately beaded headpiece created by jewelry designer Carolee Prince. Sikolo’s image hung beside Brathwaite’s portraits of two other women, Clara Lewis Buggs and Ethel Parks, photographed in front of warm-toned studio backdrops. While the portraits are spare and technically straightforward, the trio of images seemed to preside over the room. Perhaps most directly echoing Brathwaite’s work, two similarly composed photo collages by Genevieve Gaignard hung on the opposite wall. In each work, Gaignard reimagines a vintage halftone portrait, surrounding each woman with bold floral wallpaper and affixing neat rows of beads and pearls to the panels as if they were jewelry. The portraits, which feel tender, employ a sumptuous photo-visual language that has historically been reserved for white women who fit a Eurocentric definition of beauty.

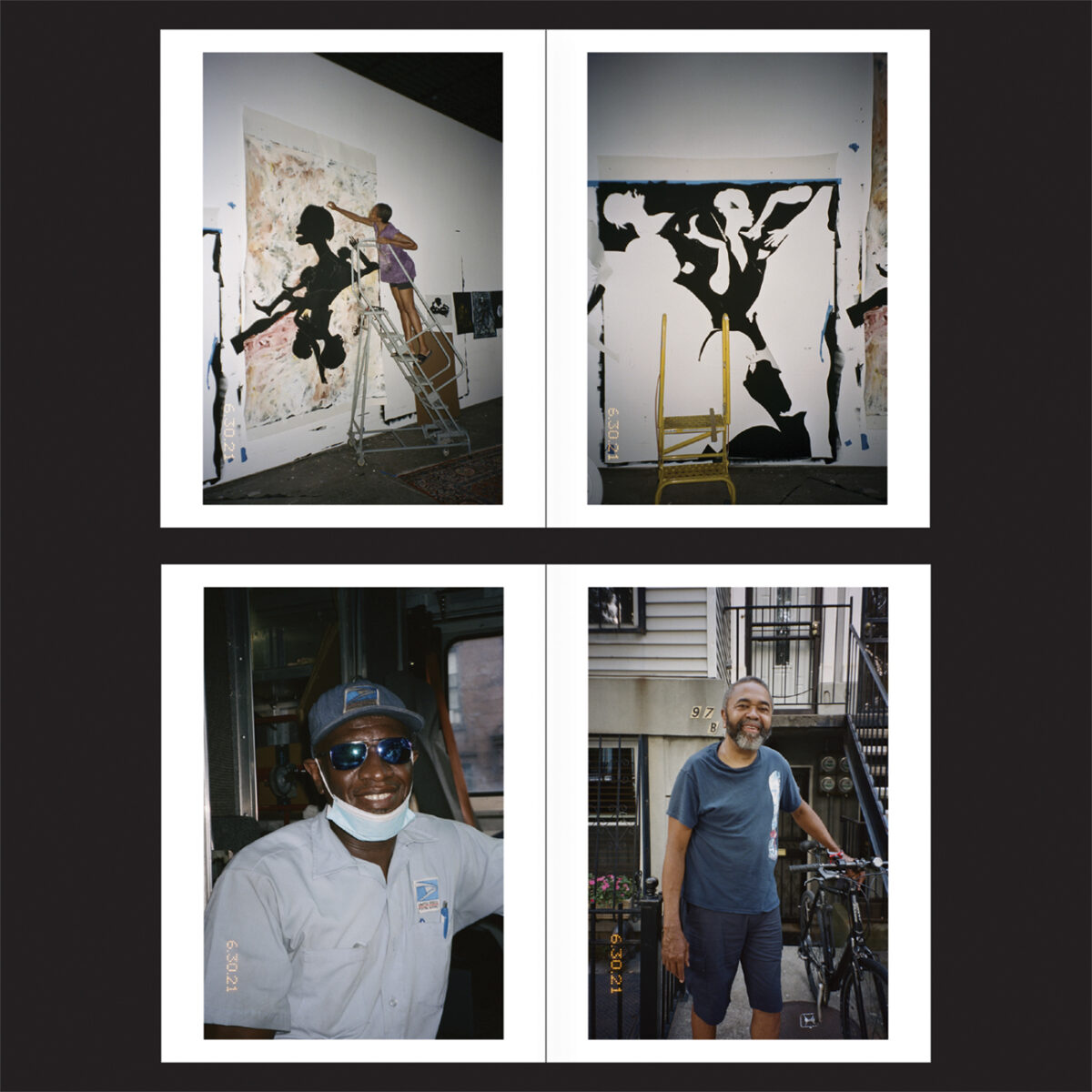

In 1956, Brathwaite and his brother, Elombe Brath (who had changed his name), founded the artist collective and social club African Jazz Art Society and Studios (AJASS), and a few years later, Grandassa Models, which centered Black women from Brathwaite’s community in Harlem. Brathwaite’s photographs worked against the pervasive whiteness of mainstream images and publications – the models in his photographs wore their hair in “natural” styles and often wore jewelry and clothing created by local Black designers. Similarly, a 2021 photograph in the show by Paul Mpagi Sepuya, Daylight Studio Model Study (0X5A2297), is an outtake from a collaboration with British fashion designer Grace Wales Bonner. Unusually (for a commission), Jerome A. Bwire and Bradley Bradshaw, the models who appear alongside Sepuya in the image, are friends of the artist, and the photographs were made in his studio – the site of much of Sepuya’s personal work. Outfitted in delicately checkered green suits from Wales Bonner’s Spring/Summer 2022 collection, two of the figures hold colorful woven fans in front of their faces. Like Brathwaite, Sepuya brings his community into the formal space of the photographic studio, creating a visual history that maps the intersection of creative lives. For Sepuya, this means centering the queer Black artists and friends who appear in his photographs – he routinely credits them by name, sometimes co-listing them as authors of the work.

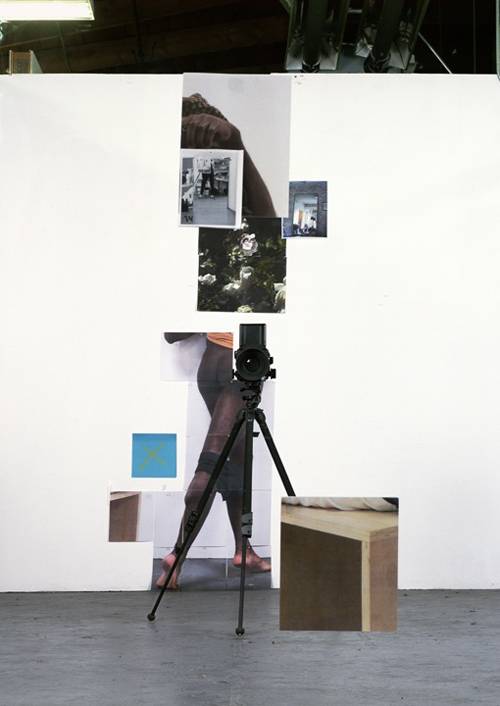

Three nearly identical 2006 photographs by Rodney McMillian, on view in a smaller room off the main gallery, initially appeared incongruent with the rest of the works on view, but they offered a helpful key to the exhibition. Each is a stark image of a plaster bust of an anonymous, suited white man purchased by the artist in an antiques store. The bust has been painted black; its chipped surface is glossy like wet coal tar. Though the man was once apparently important enough to warrant the fabrication of the bust, the decaying object in the photograph is not only unremarkable but unrecognizable – a hollow monument to perceived greatness or political pageantry. In McMillian’s simple gesture of retrieving the bust from obscurity by photographing it, he undermines the authority of the original object. Rather than cementing in stone the legacy of a particular man, McMillian creates multiples, reinforcing the notion of photography as a medium capable of upending ideas about value and legacy.

Like Braithwaite, Sepuya, Gaignard, and McMillian work against photography’s extractive legacy, in which white men used their cameras to further harmful stereotypes, expand their colonial prospects, and otherwise reinforce systems of power. Instead, they sustain photography’s parallel legacy as a mechanism of collective agency and liberation.