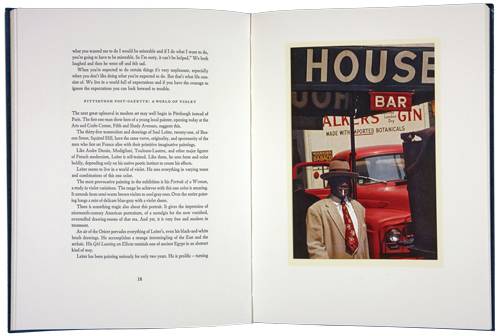

In one of my favorite portraits by West African photographer Sanlé Sory, a young man, wearing bellbottoms and white sunglasses, a fringed bag slung casually over his shoulder, casts a cool backward glance at the camera as he prepares to board a small plane, which exists only as a painted backdrop in Sory’s Burkina Faso studio. Taken in 1977, the picture is rich with possibility, full of hope and playfulness. It’s studio portrait as wish fulfillment, as curator Matthew Witkovsky puts it in the catalogue to the beguilingly titled exhibition at the Art Institute of Chicago through August 19, Volta Photo: Starring Sanlé Sory and the People of Bobo-Dioulasso in the Small but Musically Mighty Country of Burkina Faso.

Over his nearly 50-year career as a studio photographer, mainly in Bobo-Dioulasso, the second-largest city in Burkina Faso, Sory made photographs of joyful, exuberant, sexy and stylish young people, many of which celebrate the vibrant music scene there. He was the photographer for Volta Jazz, run by his cousin, and regularly photographed revelers at what he called “bush parties.” His work was little-known outside of his country until French author and record producer Florent Mazzoleni came across a number of album covers shot by Sory and organized his first exhibition, in 2013, at the Institut Français du Burkina Faso. This spring his photographs are on view not only in Chicago but in New York City as well, at Yossi Milo Gallery, which is showing Sanlé Sory: Volta Photo through June 16.

Sory’s photographs share traits with portraits by Malian photographers Malick Sidibé or Seydou Keïta (though he was not familiar with their work when he started). He offered his subjects props – a telephone, a suitcase, his own motorcycle – and various painted backdrops, including an airplane and a self-referential street scene with a sign advertising his studio, Volta Photo. Some subjects vamped for the camera, others struck a solemn pose; nearly all appear stylish and self-possessed.

Sory opened his studio in 1960, the year his country achieved independence from France, and his photographs catch a whiff of the cultural shifts occurring in the streets, the bars, and the record stores, capturing the transformation of a nation and the development of its post-colonial identity. As people moved from the village to the city, identification cards were a new necessity, and Sory stepped in to fill that need. His great gift, as Antawan Byrd puts it in the catalogue to the Art Institute show, was to “amplify” those pictures, turning the need for official portraits into an opportunity for someothing else – photographs in which the subjects took control of their own images, became the protagonists of their own stories.