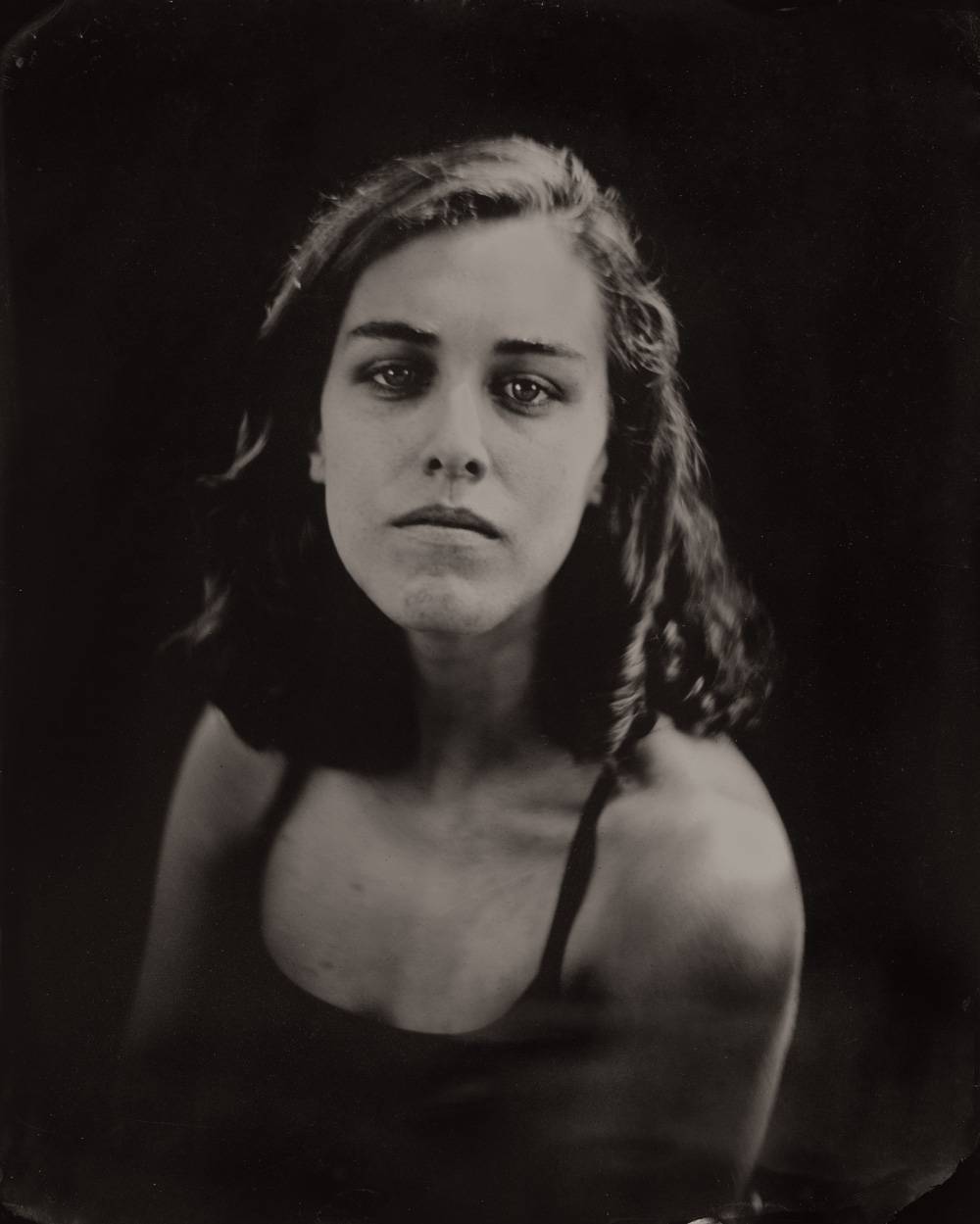

Photo by Anthony Beale

A workman from the 24 West 57th Street Gallery Building maintenance crew has just arrived, armed with a tall ladder, and Robert Anderson couldn’t be more grateful. A light’s gone out on one of Oraien Catledge’s photographs, and it needs to be replaced for opening night. (The show of socially and aesthetically affecting black-and-white images chronicling Cabbagetown, one of Atlanta’s poorest working-class zones in the 1970s, is on view through May 26.) The work gets freshly spotlit; we sit down in a slightly dimmer corner to talk—and the whole scene seems an apt metaphor for how thoroughly Anderson demurs the spotlight: “Surely there are other people you’d want to talk to besides me,” he says. “I’m not much of a self-promoter. I just like to show good work.”

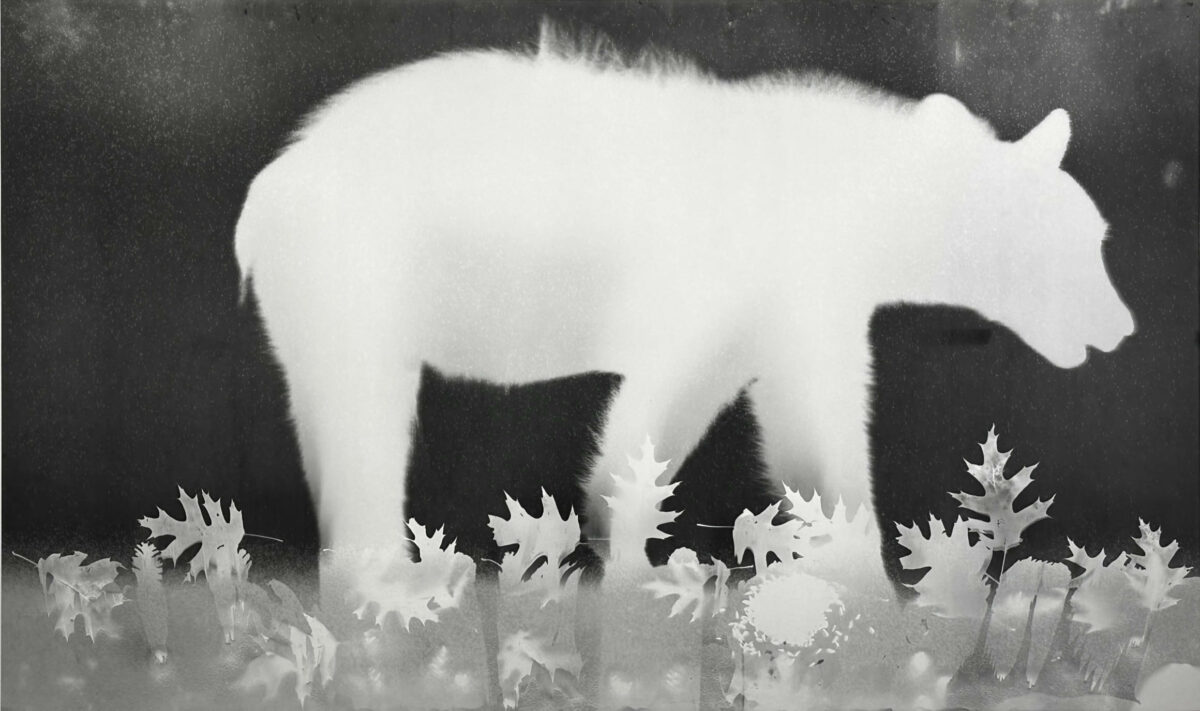

But talk we do, and in the process the vision behind the gallery—a quiet, two-room enclave of modern and contemporary photography—emerges. Anderson shows abstract photograms by Chuck Kelton; sepia-toned bridgescapes by Barbara Mensch; intense, small-scale dye-transfer prints by the late Dean Brown. All, Anderson explains, are talents many have never heard of, though they’ve built up considerable oeuvres. All are works that he would buy (and has bought) for himself. “I worked for many years in the medical world,” explains Anderson, “and I attribute my success in that field to the fact that I didn’t want the credit. My success is how well these photographers do. It isn’t me.”

Anderson is slight of frame but not retiring of presence; he works out three hours a week on his bike (a schedule “ratcheted down” from years past, when he trained for national competition races) and retains a hint of prairie twang. Born and raised in Norfolk, Nebraska, Anderson earned his medical degree at the University of Nebraska and did his residency in internal medicine with a fellowship in nephrology at the University of Colorado. In 1995, he became Meiklejohn Endowed Professor of Medicine, and in 2002 he assumed the post of Chairman of the Department of Internal Medicine —a formidable job with a $70 million endowment, a staff of 600 physicians and 150 interns and residents. Currently, he is head of the Division of Medical Humanities at the NYU Medical Center.

While he was still a young faculty member, someone gave him a camera as a present, and it pretty much changed the way he saw the world around him. As his interest in the medium grew, he began to buy work, and by the 1980s had amassed a small collection. He familiarized himself with the gallery scenes on the West Coast and in Santa Fe and befriended local practitioners. Retirement came in 2010—and with it the realization that he had the means to start a gallery. Anderson created a business plan, hired a consultant, got a framer and graphic designer, and realized his ambition to open a gallery in New York. “I came to New York in April 2010 and basically wore out two pairs of shoes looking at various spaces and seeing how much they cost. Somebody said try 57th Street.”

Today his stable is small but well defined: 50 percent are over the age of 40 and all are as dedicated to their vocation as Anderson is to his. At the gallery he is a dedicated, and welcoming, presence. “Thanks for coming in, folks,” he says as a couple of tourists enter the room. “If you have any questions let me know. I’m not ignoring you.”