Multimedia collage is a medium for our time. Referential, fragmentary, multitudinous, it gives the experience of globalization, interrelated crises, and the Internet a visual language. It is also an apt form for describing selfhood as the amalgamation of influence and experience, ever in flux.

But what if others saw you not as a whole made up of dynamic parts, as we all are, but as reducible to one flattened fact? The Black children depicted in Deborah Roberts’s What about us? – her first show in New York City in more than five years, and the first exhibition at Stephen Friedman’s new gallery in Tribeca – gaze back at the viewer, refusing to be reduced. Composite faces made from multiple photographs join bodies of acrylic, graphite, pastel, ink, and collaged paper. They are larger than the subjects in her previous works. A monograph, published by Radius in conjunction with the exhibition, reproduces more than 20 years of Roberts’s work alongside essays by Dawoud Bey and Ekow Eshun, and a conversation between Roberts and Sarah Elizabeth Lewis. Full of movement, colorful patterns, and complex emotion, these pastiches are what the artist has called “all children and no children.”

Their eyes hold lifetimes of being looked at without being seen. Those of the boy in I’m starting with you (2023) seem to convey an invitation and a compact – the agreement to look, not to look away. Roberts’s characteristic white background gives way here to shades of black in the background and in his shirt and skin; the boy’s dark outstretched palm fills half the canvas. Hands speak as eloquently as eyes in these works, and in Come and see (2023), the girl’s hand is an extension of her gaze. I come alone (2023) is a study of hands; gently clasped and painterly palms form a gesture that could equally express play or plea.

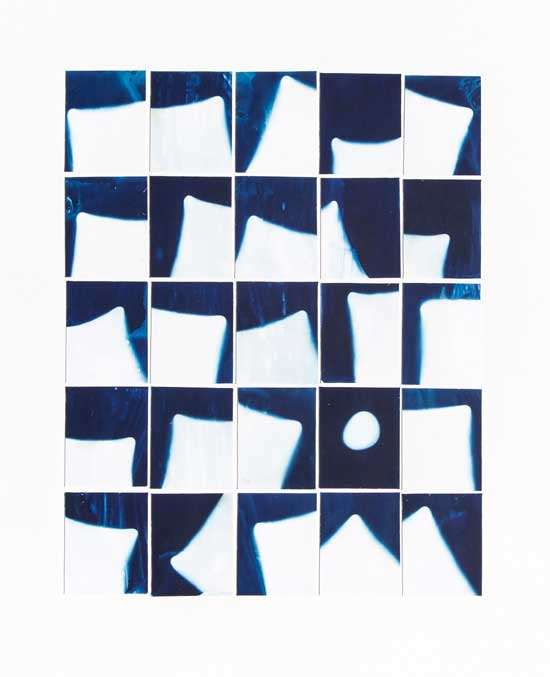

One of two particularly large works, Girl / woman forever a work in progress (2023) communicates the parallel processes of coming into oneself and making art. Blue painter’s tape remains, permanent and exposed, affixed to ample negative space. Unfinished is not a failure here, but an aesthetic. This complex work conveys that jarring, joyous disjuncture of becoming. We all deserve the freedom and safety to explore who we are without the threat of “constricted expectations and possibilities,” as Bey writes in his foreword, not to mention brutal violence. In Tomorrow, tomorrow and tomorrow (2023), a boy – doubled – runs towards his mirror image, one side dark, the other light, as if a negative of the self: one palm a raw pink, one matte black, and a brown photographic hand to bridge the two.

What Roberts has called “the adultification of Black children” is perhaps best illustrated by a boy in Adidas stripes. He takes a knowing, arms-crossed stance of a man only to be given away by his Tweety bird cap, his child’s mouth cautiously forming a half-smile. It would be a violent distortion to see a man here, but the viewer knows this boy may well be judged as such. Roberts said the work was inspired by Ralph Yarl, a sixteen year old who, when he accidentally went to the wrong home in Kansas City, was shot by an eighty-four-year-old white man. I was reminded of a question posed by Emily Raboteau in her forthcoming book Lessons for Survival: Mothering against the “Apocalypse” (Macmillan), a meditation on parenting Black children in America in the age of climate crisis, far-right ascension, and race- and gender-based violence: “When would they stop seeing him as a child and start seeing him as a problem?”