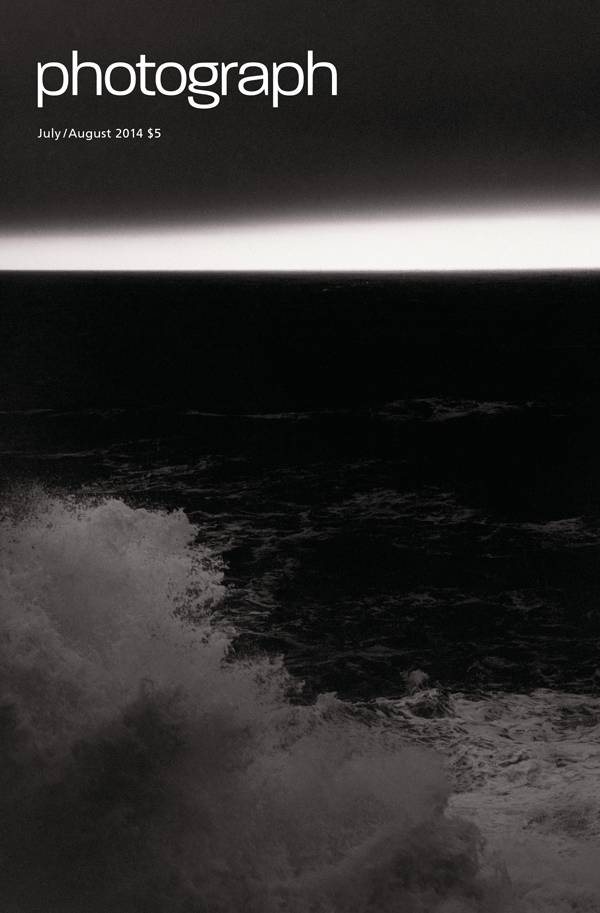

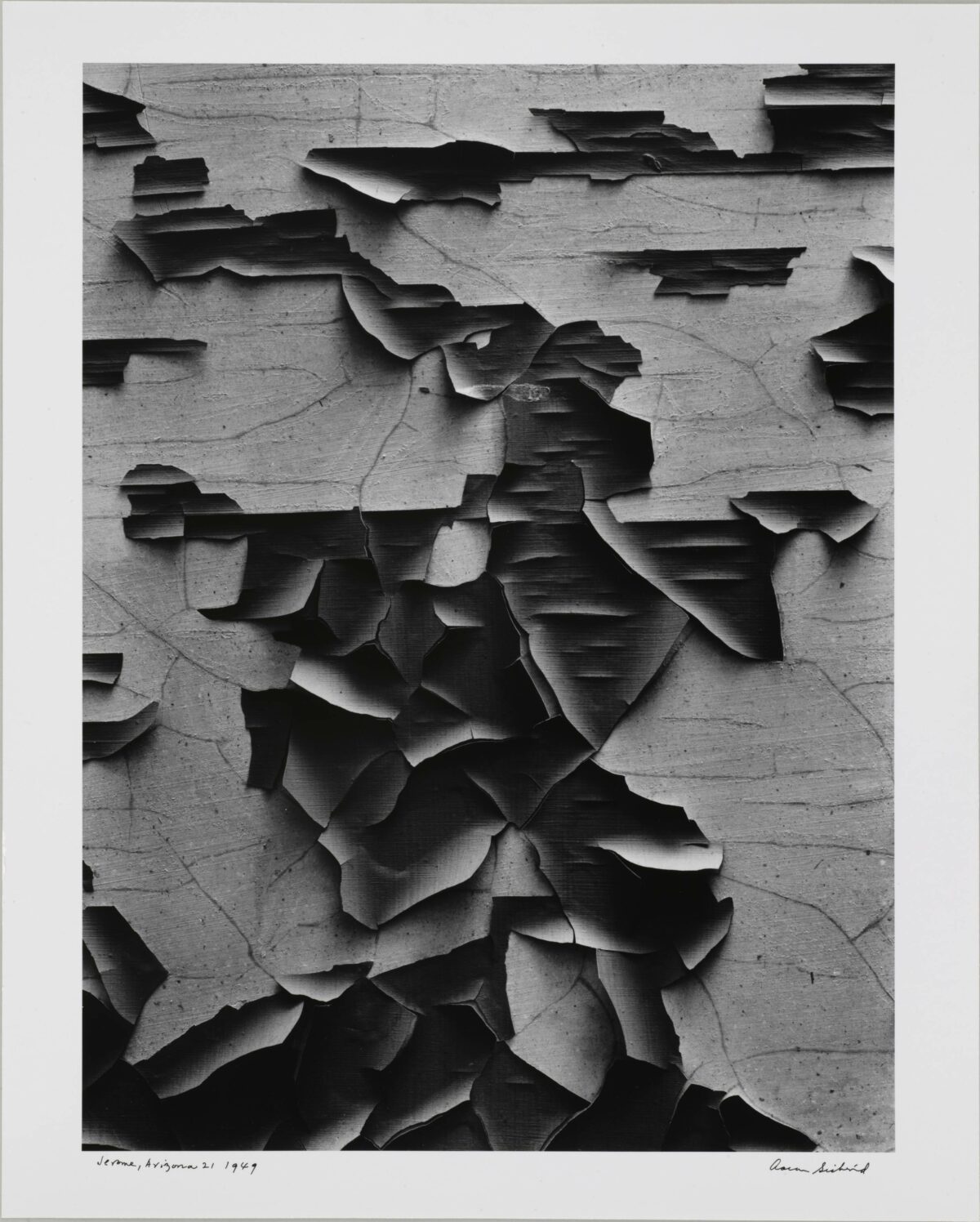

“After such knowledge, what forgiveness?” wrote T.S. Eliot inGerontion. The words ring harshly true in the case of Minor White, one of the best-known and most-ignored American photographers of the last century. Most ignored? The co-founder of Aperture magazine, a catalyst for photo programs on two coasts, one of the greatest photo teachers ever, with an influence through a vast network of students too elaborate to be charted – ignored? Ignored because the vision of photography White championed, a spiritualized, transcendental idea of photographic form, originating deep in the soul of the photographer, has been disparaged and deconstructed over the last four decades by critics and photographers. We know too much about a diverse world to accept the windy universalizing, they say. Too much freight for pictures of water (like our cover, Shore Acres State Park, Oregon), rocks, and winter ice to carry. Yet the J. Paul Getty Museum, with the first true White retrospective (July 8-October 19), is making a committed rejoinder. Paul Martineau, who curated the exhibition, advises us to put aside the metaphysics and look again at the mood and texture of the images, and not be afraid to embrace the notion of visual poetry. “In a time when we are bombarded with images, Minor’s photographs encourage us to take the time to look and allow ourselves to be moved,” he says. And whatever the photos’ intended meanings, in Martineau’s estimation they continue to do what White hoped they would: provoke associations, expand consciousness, “and get the imagination going.” Shore Acres is a remarkable photographic object, a study in impossible light that becomes more paradoxical, more photographic, the longer we look. It’s a suggestion about nature rather than a picture of it. Such a defense is not new. White’s acolytes and defenders have pointed to the open-ended abstractness of his imagery and the subtle richness of his prints. What is new is the exhibition’s revelation of the energetic source of this expressiveness. White was a gay man, closeted by choice and necessity, firmly believing that his sexual longing could and should be channeled in more universal directions. Martineau has chosen to display for the first time the complete seriesThe Temptation of St. Anthony Is Mirrors, White’s 1948 celebration of his student Tom Murphy. The appeal to the senses is anything but abstract, and it exposes White as a sensualist of the eye, whose spiritualizing of his subjects was compensatory but also ecstatic. White was anguished about his sexual feelings, and the anguish comes through in the famous allegorical series Steely the Barb of Infinity, which includes Shore Acres, begun after a disastrous relationship in 1960. The pictures are symbolic, but they are felt metaphors, inviting viewers not simply to read them but plunge into them, to immerse themselves in the bodily sensations of desire, pain, and renunciation. White’s lesson is not that the universe is One, but that everything has a body (including photographs), and the body is where spirit, imagination, world, and desire meet.

Categories