If the photogram is ordinarily associated with a shadowy ephemerality, San Francisco artist Klea McKenna’s approach to the form invests it with a physical heft more often linked to printmaking, or even sculpture. While the making of a photogram entails, by definition, contact between object and light-sensitive support, McKenna’s “photographic reliefs” incorporate tactile impressions of her subjects, a criss-crossing of shallow dips and ridges produced by rubbing and accentuated visually in the darkroom. It’s an effective tweak to a simple method that provides the artist with a usefully direct way to represent both natural phenomena and, in her most recent work, fabrics and used-clothing articles infused with cultural-historical significance.

McKenna, the daughter of “renegade ethnobotanists” Kathleen Harrison and Terence McKenna, was raised to be comfortable around untamed nature, so it’s no surprise that the earlier works on display in this, her New York solo debut (on view through November 10), focus on the patterns of forest life. Two entries from the Automatic Earth series depict cross sections of trees, their internal rings like concentric ripples on the surface of a lake. And a trio from the same year’s Web Studies shows the webs of orb-weaver spiders glittering with accumulated raindrops. In one, the fleeting impression of a departing arachnid is visible as a pallid, ghost-like smear. It’s worth knowing that these works were made partly in situ, dense foliage acting as a kind of outdoor darkroom.

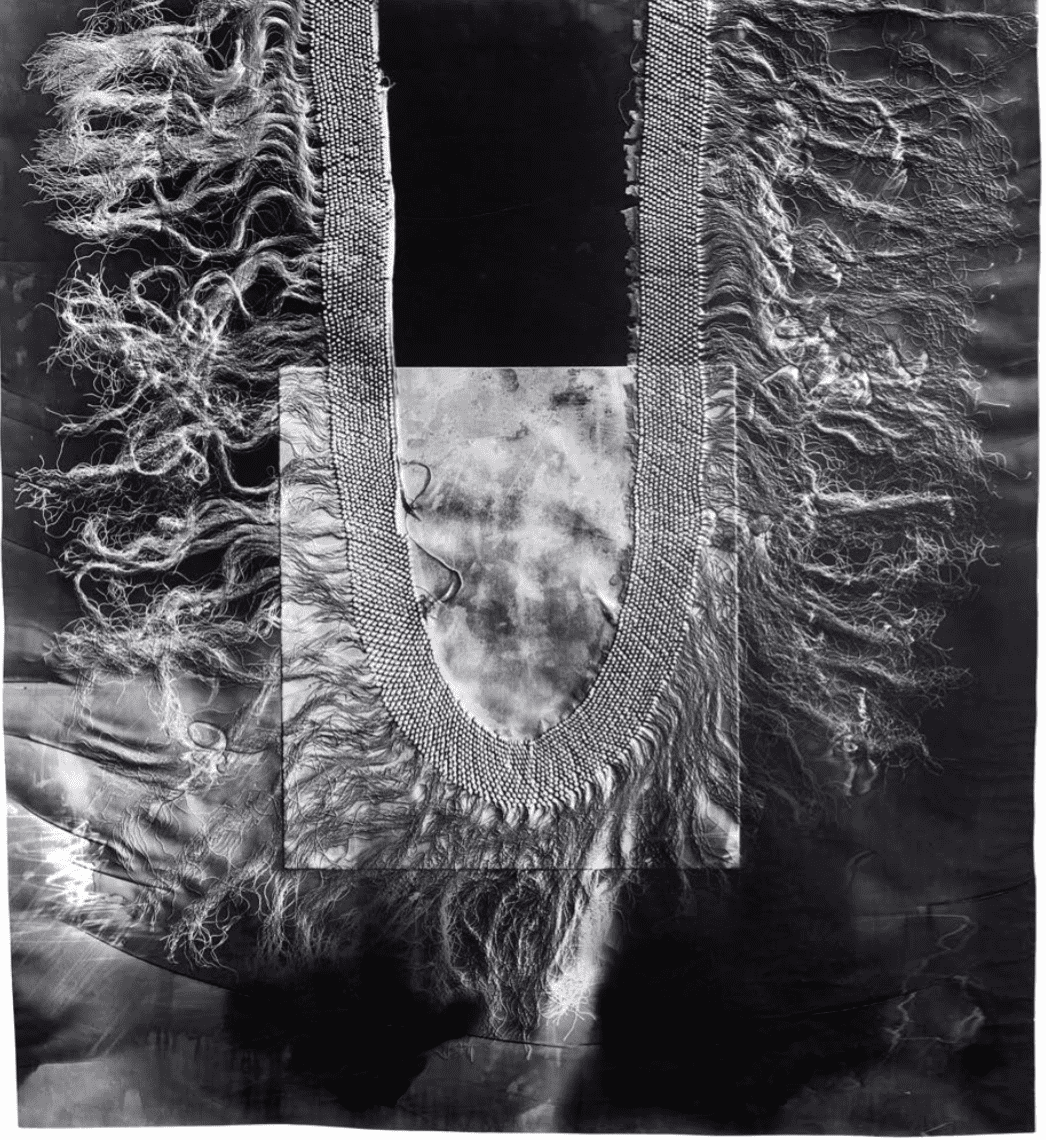

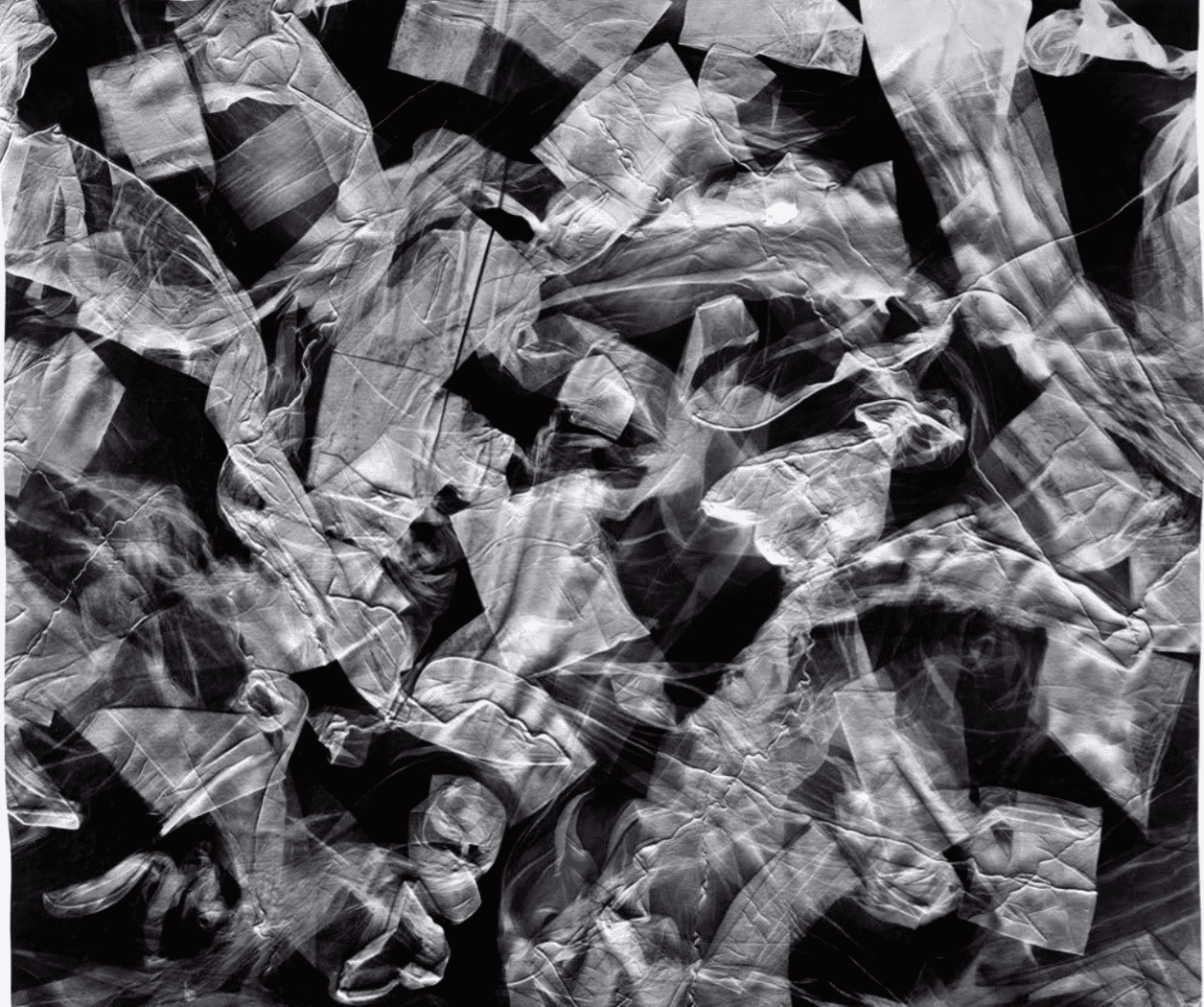

In her Generation series, McKenna redirects her lens toward the human realm, depicting textiles transformed by wear and tear into haunting records of women’s experiences – narratives removed from McKenna’s own by the specificities of time and place but united with it in other ways. La China Poblana (1), 2018, for example, embodies a fascinating intersection of cultural identities in its depiction of an old skirt encrusted with sequins. This traditional garment tells the story of Rajasthani woman who, in the late 1600s, was kidnapped, sold into slavery, and taken to the Mexican city of Puebla, where she eventually married a wealthy merchant. And in Paint Me Bare (3), 2018, a tangle of 1960s-vintage nylon stockings evokes a different but similarly multilayered story, in which a garment embodies both technological innovation and the stubborn persistence of archaic gender roles.