Look up, near the ceiling surrounding the large, L-shaped, wooden front desk at Leica Gallery on Broadway in Greenwich Village and you’ll find the autographs of some of the greatest photojournalists and aesthetic documentarians who ever snapped a shutter: Inge Morath, Ralph Gibson, Larry Towell, David and Peter Turnley, William Albert Allard. Since Leica Gallery’s inception in 1994, the proprietors of the gallery, Jay and Rose Deutsch, have made it a tradition to ask the photographers who’ve shown with them to sign their respective exhibition posters (some 118 to date), and the sight of them hung, three-deep and cheek-by-jowl all the way up to the ceiling, makes for an impressive visual archive. Custom-built wooden bookshelves behind the desk are filled with titles that would thrill any photo-enthusiast’s heart: Sometimes Overwhelming by Arlene Gottfried; Magnum Stories; and Walker Evans: The Hungry Eye, to name a few. A glass case to the left displays some of the precision cameras and rangefinders for which Leica is famed. The latter aren’t for sale, but those selfsame signed exhibition posters (unframed) are. Just page through a binder farther back in the four-room gallery and choose the one you want for a whopping $10 ($30, perhaps, for one of the rarest). “We like to keep them affordable for all the local NYU students who stop by,” says Rose.

Leica, based in Solms, Germany, plays its role in the gallery as a kind of beneficent corporate entity, lending its name (not to mention the aesthetic imprimatur of the Leica brand), and leaving the Deutsches alone to do what they do best: craft shows packed with both academic gravitas and public appeal, not to mention their decidedly sophisticated, Gotham-inflected style. Jay and Rose have been together since 1965, soon after Jay successfully followed up on a double date the couple went on while in high school in the Bronx (“We were, of course, dating the other couple that night,” Jay recalls. “Isn’t that the way it always goes?”) They married in 1966 and lived out some pretty peripatetic years while Jay served an eight-year tour in the Army’s Medical Service Corps. In 1976 the couple came back to New York—“in a VW,” as Rose tells it, “with two children, a dog, and a cat, ready to join the family business.” That was the Deutsch’s hat-trimming concern, which went back generations on Jay’s side and included the ownership of 670 Broadway, then a factory loft building. When the hat business dissolved in 1989, the Deutsches divided up the floors and converted them into rental units, taking over one themselves on the fifth floor and opening up an art gallery called “FDR,” where they sold works on paper by contemporary and 20th-century artists.

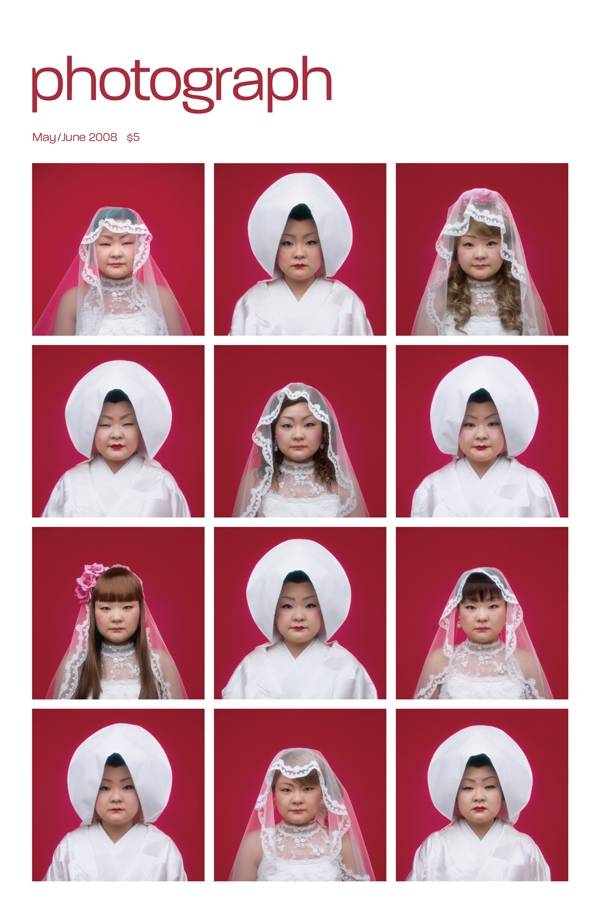

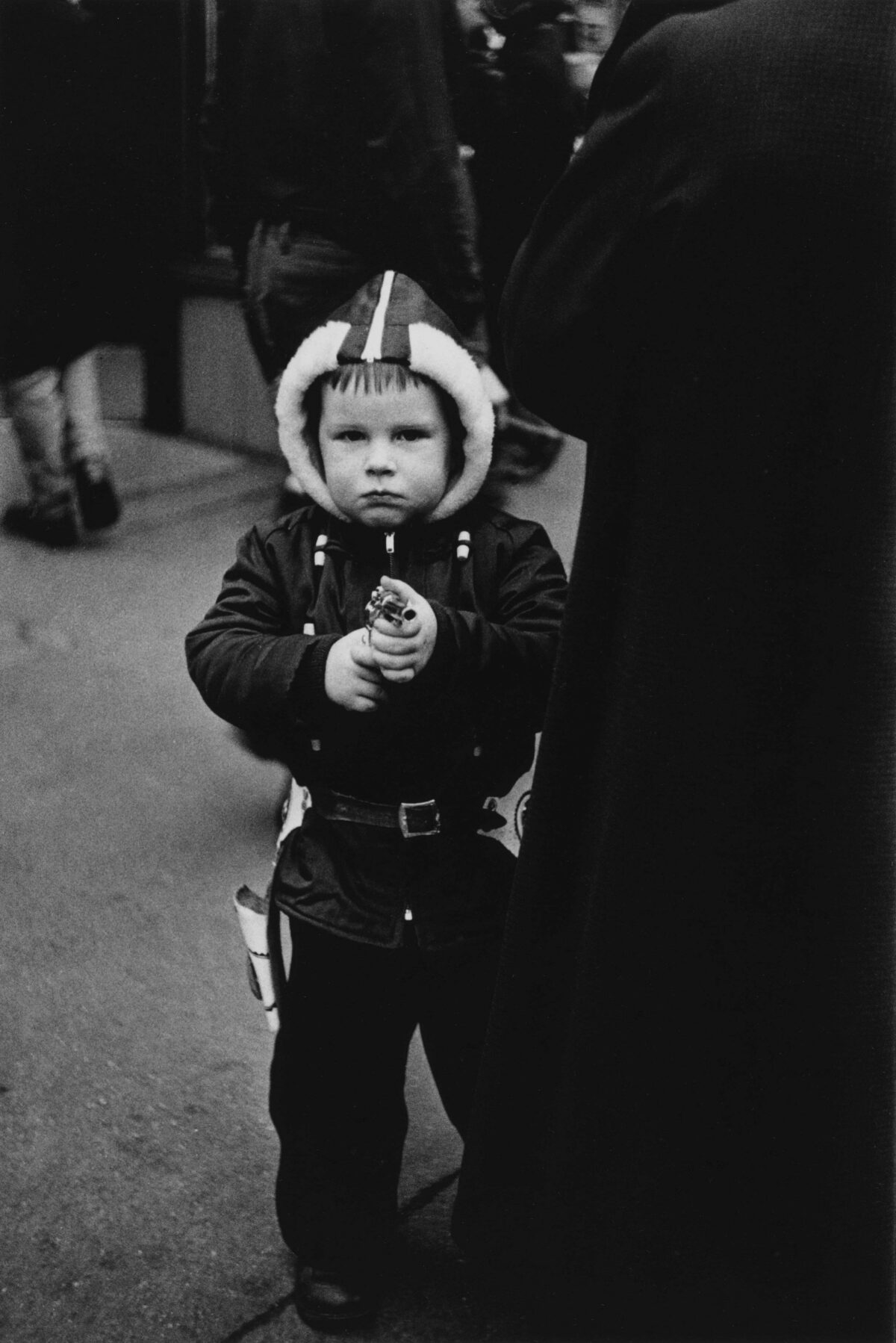

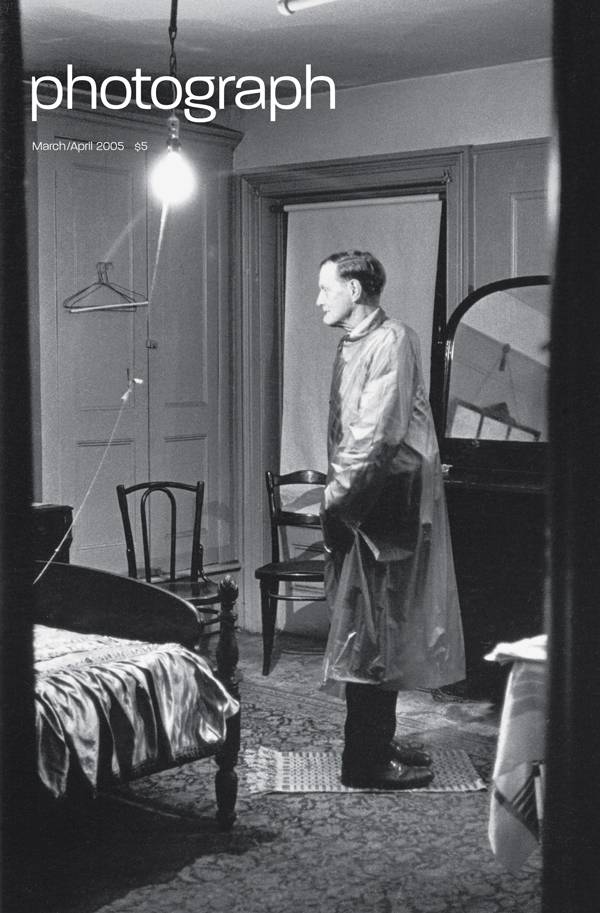

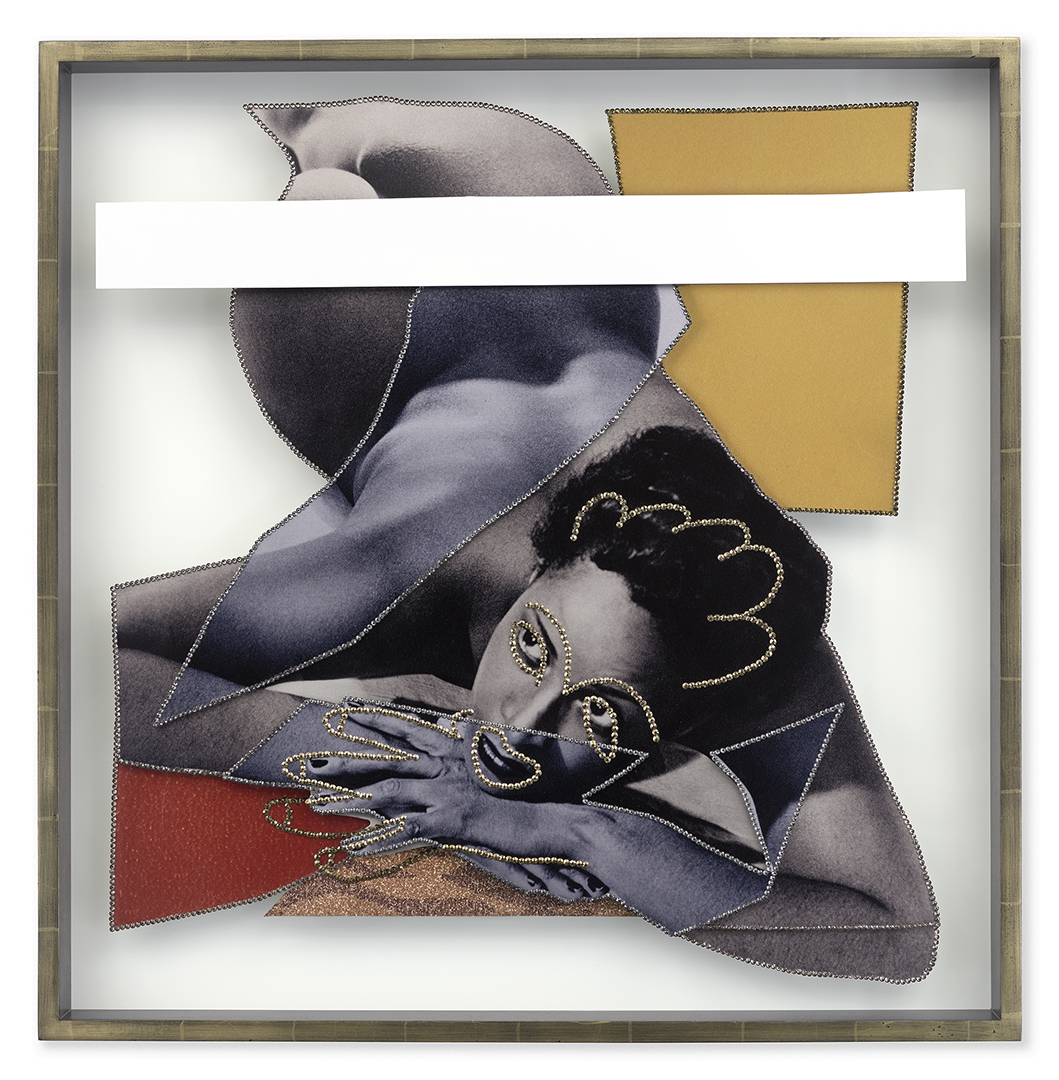

In 1994, Jay approached Leica, which at that point had one gallery at its German corporate offices, about entering into an association. The focus of the gallery would be on images either taken with a Leica, or by Leica-favoring practitioners. The company accepted, and the rest is history: solo exhibitions by masters who have used the camera’s near-silent shutter release to capture intimate moments in the halls of power; shows with larger themes like Aging in America by Ed Kashi, Saturday Night Sunday Morning, with its candid glimpses of African-American lives, curated by Deborah Willis, or a recent show, Anton Kratochvil’sMoscow Nights, 2007, images of Russian nightclubs. “People often stand at the door and jokingly ask me, ‘I have a Canon, may I enter?’” Jay says. “We say, everyone’s welcome. Whatever paintbrush you use.”