Seventy-fifth Street between Lexington and Third is a pretty sedate residential block on Manhattan’s Upper East Side. Yet it’s there—nestled between century-old townhouses—that you’ll find Tom Gitterman’s new photo gallery. It’s a decidedly more homey setting than the windswept, industrial blocks of Chelsea. And if Gitterman looks particularly comfortable in his surroundings, there’s no accident in that. “I also live here,” the New York native confides, pushing open an unassuming sliding door, “How else could I afford all this?” He hasn’t finished speaking the words, and voila, revealed for inspection are a queen-sized bed, overstuffed pillows, a pair of teddy bears, the clutter of clothing. On the other side of the room’s threshold is your typical white exhibition space, spotless to the point of being pristine.

“Ask me anything, I’m an open book,” says Gitterman as an assistant serves us a perfect espresso, made in a full-service kitchen hidden somewhere behind another spotless wall. He is 37, boyish, bearded, with blue eyes to match his blue shirt. His voice can get very soft at times—usually right before a spontaneous laugh. Though many would consider him one of the freshest faces among photo dealers, Gitterman has been working in the business for quite a while. Most recently he’d been dealing out of his former West Village apartment. But he really made his name running Gallery 292, and later the Howard Greenberg Gallery in SoHo—directing the space, shaping the shows, and making good contacts of clients and artists. Greenberg was a kind of mentor to him for eight years, and a four-year stint at Zabriskie Gallery when he was fresh out of college didn’t hurt either. It was Zabriskie’s strong presence in Paris that gave Gitterman a French connection, one that years later informed his inaugural show—the heretofore undiscovered life’s work of a master Paris photographer named Jean Moral (1906–99).

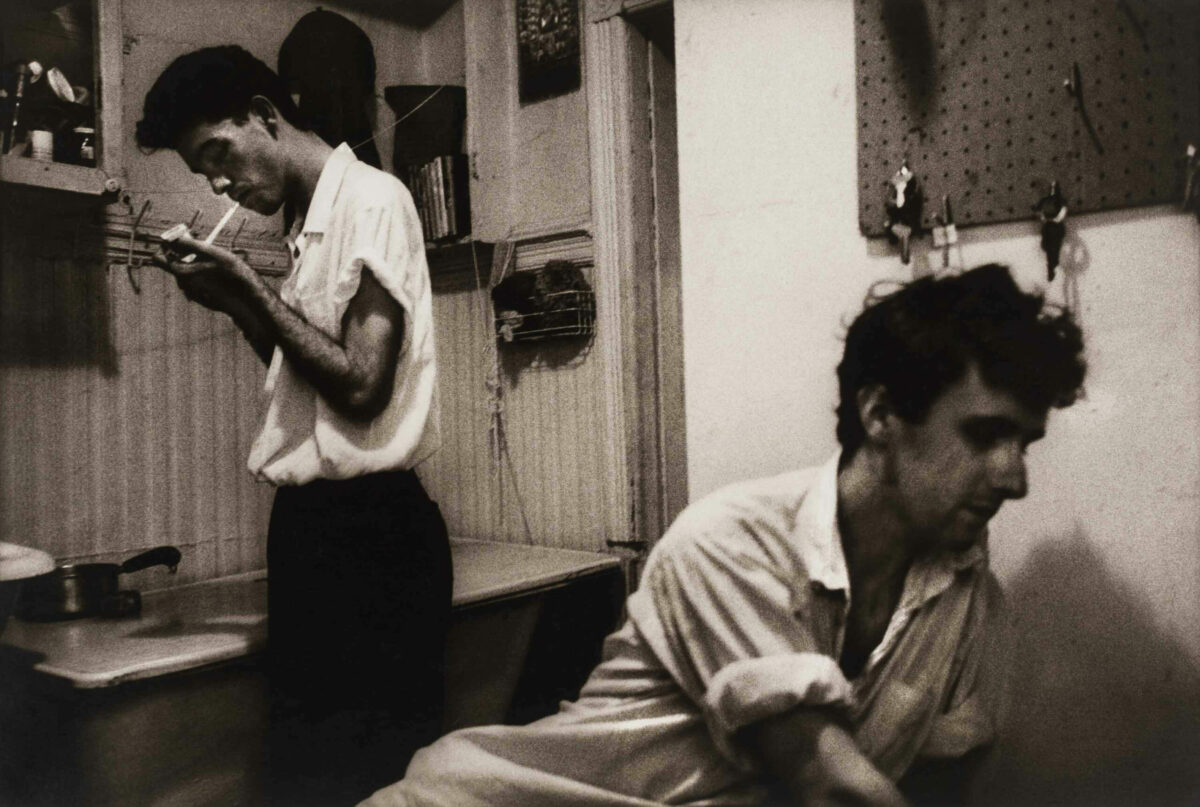

Moral nicely epitomizes at least the first half of what seems to be Gitterman’s raison d’être as a gallerist: vintage work that is somehow fresh or undiscovered. As for the contemporary work, it too must be fresh, but also of a photographic quality that, as Gitterman puts it, “broadens my perspective of traditional dialogues with the medium.” This translates—much to his credit—into contemporary artists both new and mid-career. Joshua Lutz, for instance, is a 29-year-old former student of Stephen Shore who got his solo debut at Gitterman’s last summer. Was Gitterman taking a chance showing an unknown? Yes, he admits. But, in his mind, Lutz’s urban landscapes were of such undeniably high quality that it seemed almost ridiculous not to. Roswell Angier is head of the photo department at Tufts, and until Gitterman showed his photo documents from the ’70s of strippers and other denizens of Boston’s tough Navy port area last month, they had been languishing in obscurity. This spring, look for the work of Pratt and ICP professor Allen Frame—another mid-career Gitterman “find.” “Whether it’s secondary market work or work I exhibit, it all has to be of the same quality, really,” says Gitterman. “I’m not so arrogant as to think that I don’t need to make a name for myself. I want to show artists who aren’t associated with other galleries. I’d like my gallery to be a destination spot.” The doorbell rings. A couple of elderly ladies passing by the front window decide to stop for a look. Gitterman greets them warmly as he makes short work of removing the coffee cups and clearing the table. “Let me know if you have any questions,” he says. “Make yourself at home.”