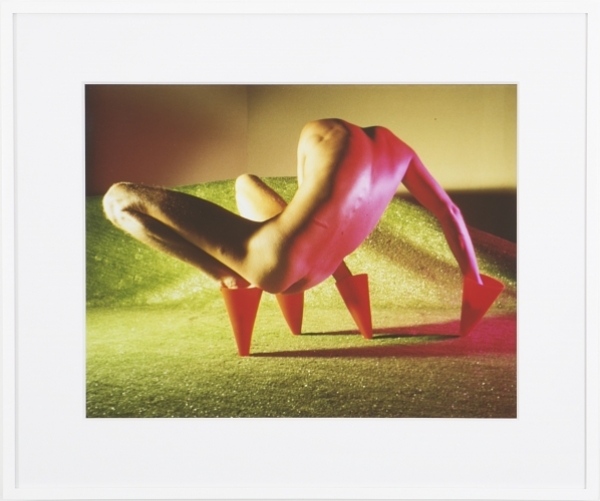

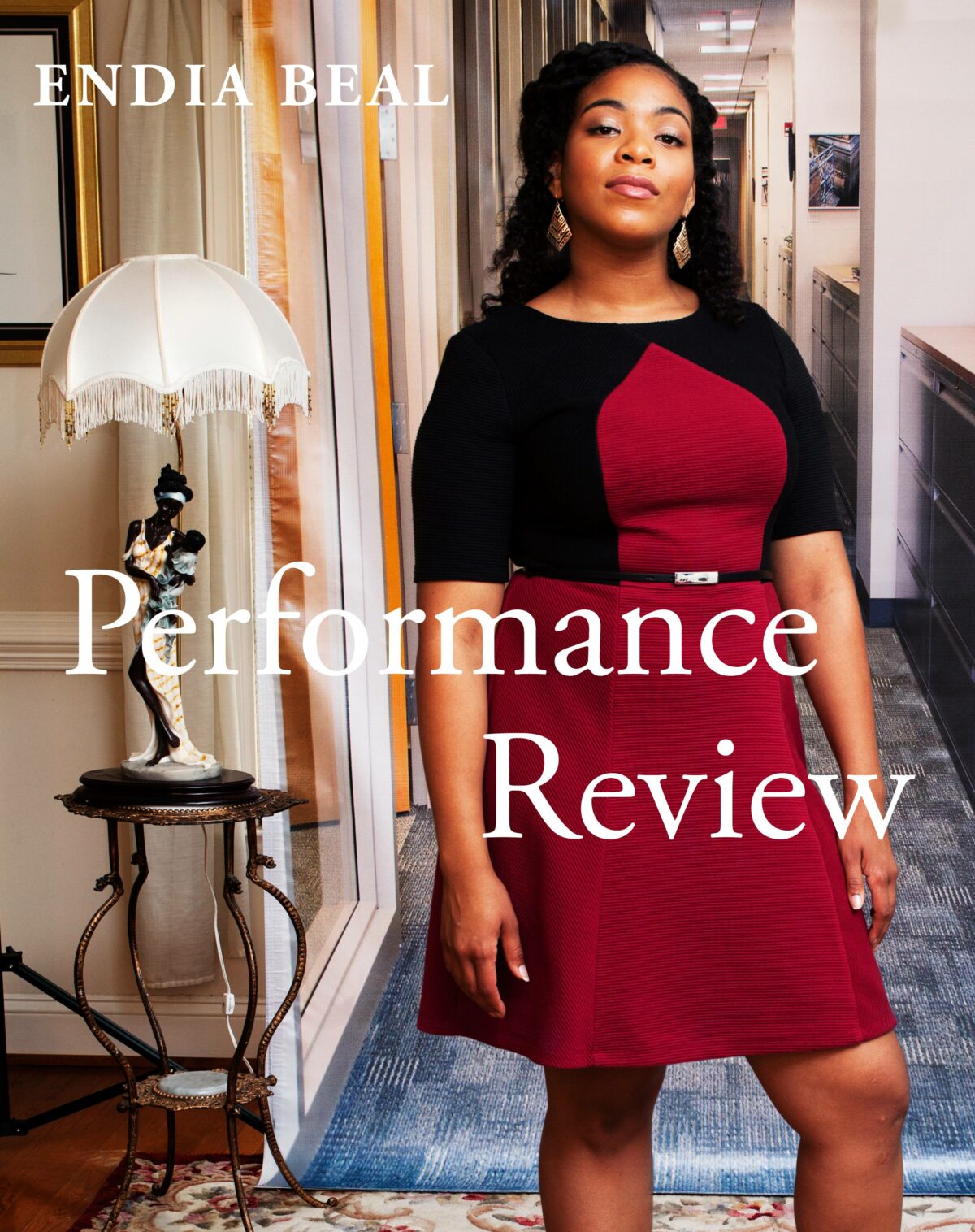

A putative member of the so-called “Pictures” generation – a group of photographically inclined artists identified as conceptual at the end of the 1970s – Laurie Simmons has produced work over four decades that is more diverse and elusive than any label. She is perhaps best known for her work in miniature, photographing constructed environments and tableaux with a distinctly feminist take – an approach that inspired her daughter Lena Dunham’s first film, Tiny Furniture. More recently, Simmons has embraced both human-scale portraiture and filmmaking. Her work was on view earlier this spring at Salon 94; another body of work is at Mary Boone through July 27. In October, the survey exhibition Laurie Simmons: Big Camera/Little Camera opens at the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth in Texas.

Lyle Rexer: I had a chance to go back and look at some of your earlier work, especially the series Early Black and White and the color interiors, and it struck me that something fundamental was missing from discussions of your work, namely, your interest in photography as photography. I see you trying out all kinds of strategies to see what cameras do to the things they capture. You appear as an artist of photography, not just an artist using photography, if you know what I mean.

Laurie Simmons: I am glad you picked up on that. I should say that I walked out of my introductory undergraduate photo class at art school, so when I finally began to make pictures, I realized I had to teach myself photography. That’s when I began to indulge the photo geek in me. I would have said at the time that those black-and-white pictures were almost abstract. I couldn’t face the content. I wanted to confuse the eye, to make people think of parts of the rooms as real, even as I messed around with them – tilting the walls and finding odd perspectives. I was inspired by Gordon Matta-Clark’s photos of the abandoned buildings he sliced in half. I was actually inspired by all the pictures that documented conceptual art actions. At that time, in the art world, there was pressure to position oneself. I had to indicate that I was conversant with the more academic or conceptual aspects of picture making.

LR: The idea of using a doll house, and more generally miniatures – does that have something to do with a fascination with childhood?

LS: As a child I was never very interested in playing with dolls or dollhouses. In my 20s I used the spaces of the dollhouse to learn about shooting pictures. I was very nervous about being called out for not knowing the craft of photography so in a sense I was continuously practicing.

LR: More recently, especially in the show at Salon 94, you have left the “tiny furniture” behind and turned to human portraiture. In comparison, the portraits seem more…

LS: Serious?

LR: I was going to say more intense, confrontational, darker. Maybe it’s the scale.

LS: I think there is plenty of darkness in my earlier work. The series Clothes Make the Man has a very dark side – maybe not so obvious at first.

LR: Ventriloquist dummies with vaguely obscene thought balloons – it’s a perfectly negative caricature of hypersexualized male mental life. Is that how you felt at the time?

LS: It’s hard to reconstruct what I was thinking, but it was probably my attempt to imagine what was going on in men’s heads, which I had always wondered about. Some critics hated it, The New York Times especially. The writer thought it was reductive and simplistic, which it was. It was really disconcerting to see everyone just shut down in front of that work.

LR: I bet. I’m sure you heard, “Men don’t really think like that,” except that in the age of Weinstein and Trump, it seems clear that they do, and there are some pretty terrible consequences. So it makes great sense to bring this work back, and now it really does have an edge. But I want to get back to the portraits. Here again, I don’t think critics are talking enough about these portraits as photography and what we expect from that genre, especially now when so many people are making portrait-ish photographs.

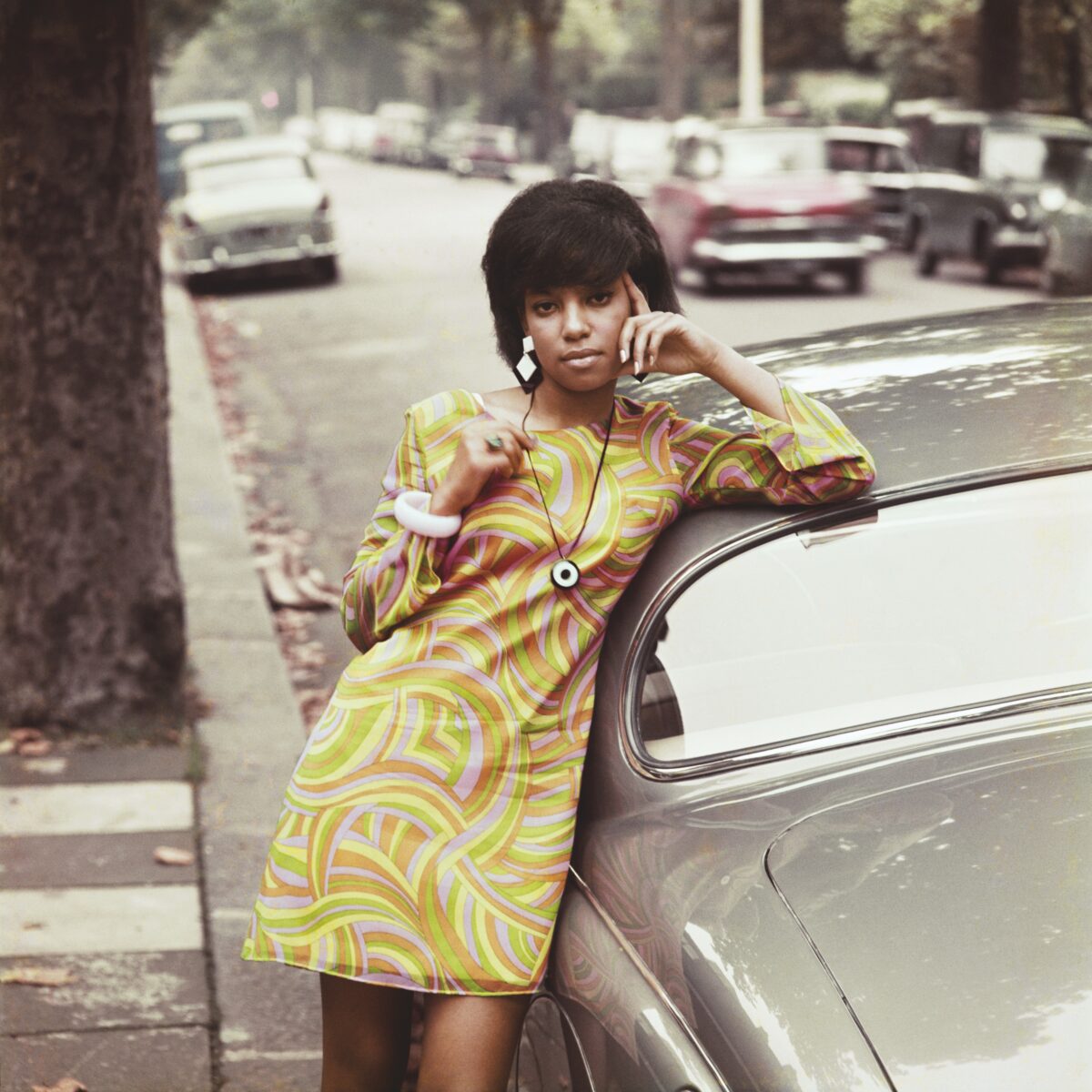

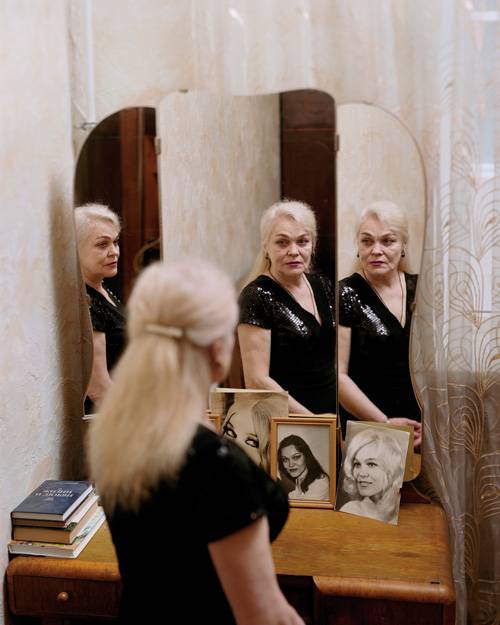

LS: I felt that to do something worth looking at in a familiar genre like portraiture I needed an excuse – a way in – to maybe desecrate it, to challenge it. I don’t want to offer a straight-up view of another person’s reality. I want to distract people as well as myself. So in the series More New I had the models’ and subjects’ bodies painted in a trompe l’oeil effect to deceive viewers. In How We See, I painted on the closed eyelids of fashion models. I’ve managed to stay inspired by continuously going down the rabbit hole of the internet, looking at make-up videos and the elaborate selfie culture and its conventions and all the strategies of digital correction and enhancement. When I started in photography I used to say that all photographs are pretense and lies. With selfies we are seeing a whole new level of pretense and lie. That excites me.

LR: I know you were inspired to shoot human subjects in part by your encounters in Japan with cosplay and anatomical love dolls, but it seems to me the way to portraiture was really opened in that collaboration you did with the artist Allan McCollum, where you photographed hand-painted miniature figures in extreme close-up.

LS: Yes, that really is true, and I love that you remember those pictures from 1985. Actual Photographs, we called them, and we shot them with a super magnifying camera. We got tiny HO train figures from Germany and worked out strategies of portraiture with them. But of course, at that level of magnification, the hand painting, which looks vaguely realistic to the naked eye, becomes grotesque – the approximation of a face. But the more we shot, the more the figures began to take on distinct personalities.

LR: As if they were actual people – and not just actual photographs.

LS: But that is what photographs do to inanimate likenesses – dolls, dummies, figurines. They imbue them with life.

LR: Your feature film My Art strikes me as your most decisive and certainly riskiest change. Whatever we think of the film, its personal nature is unmistakable. Given the boldness of your daughter and her success, I am tempted to say: what took you so long?

LS: I sometimes ask myself the same question, since I had been moving toward time-based narratives since I started taking pictures. I think we take risks to stay interested, to raise the bar. If you’re vaguely embarrassed, it usually indicates that you are on to something new that might actually be something worth fighting for. In 2006, I made The Music of Regret, a film musical in three acts, a kind of animation in real time with plastic dolls and puppets and the Alvin Ailey dancers, and it turned into my film school. I learned so much from working with cinematographer Ed Lachman and Meryl Streep. The film world is a kind of scary place for me. You have to remember the world of photography was wide open to women in the 1970s and ‘80s – little more than 100 years old and ready to be colonized. The film world, like painting and sculpture in the art world, felt very male dominated. It had a Keep Out sign.

LR: I assume you will continue to make photographs but will you ever go back to the little world?

LS: I have a box of stuff in my house, all kinds of plastic figures and objects and sculptures that I’ve continued to gather along the way. It has a label that says: To Be Photographed. But I increasingly doubt I’ll get to doing it.