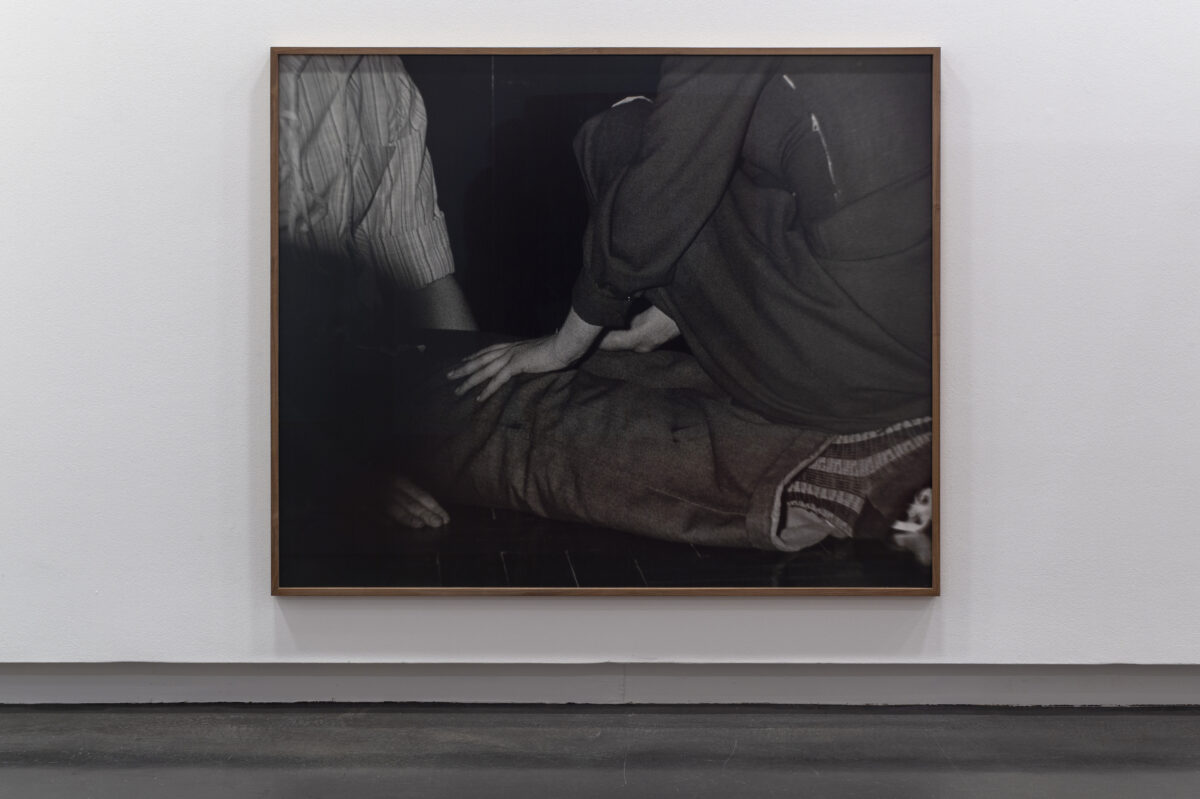

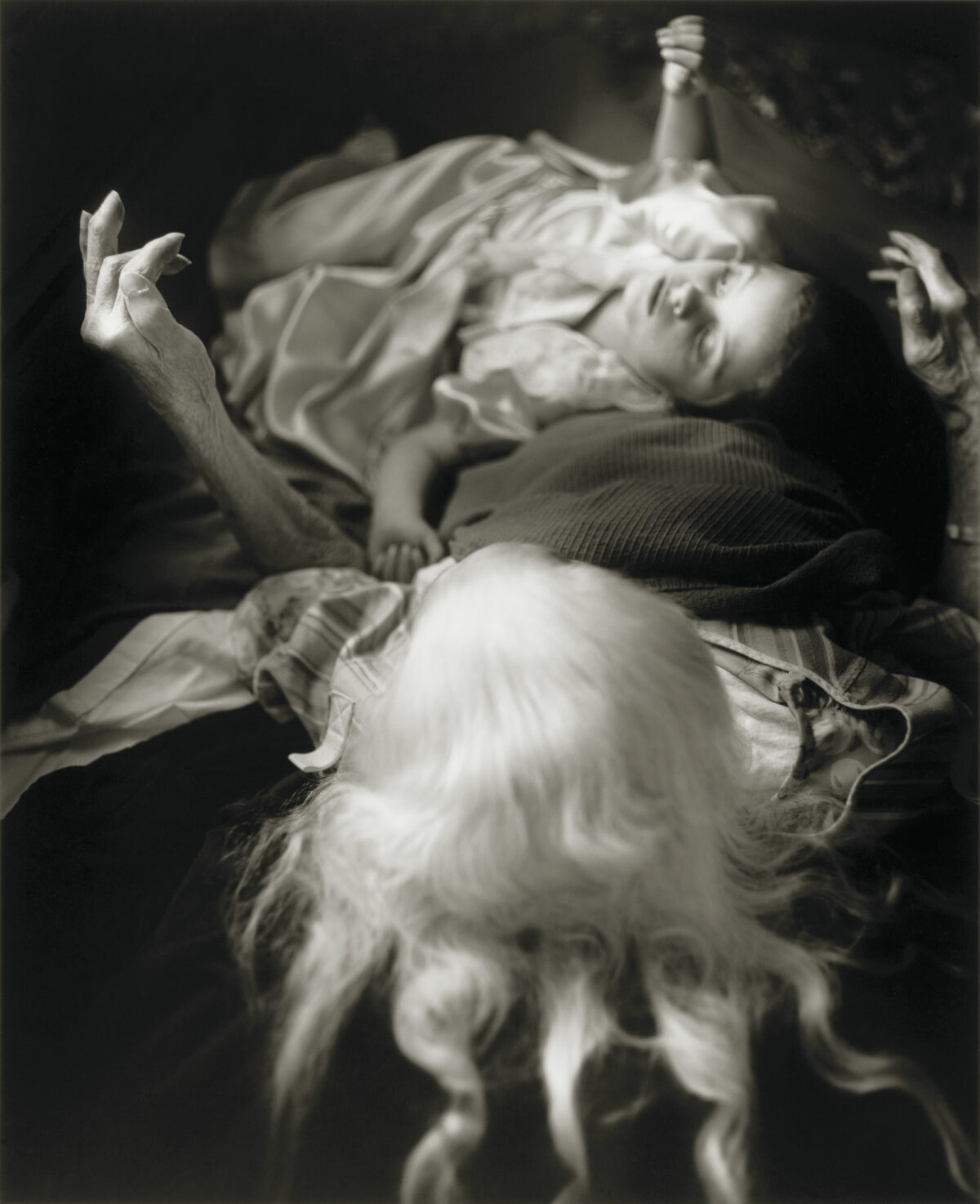

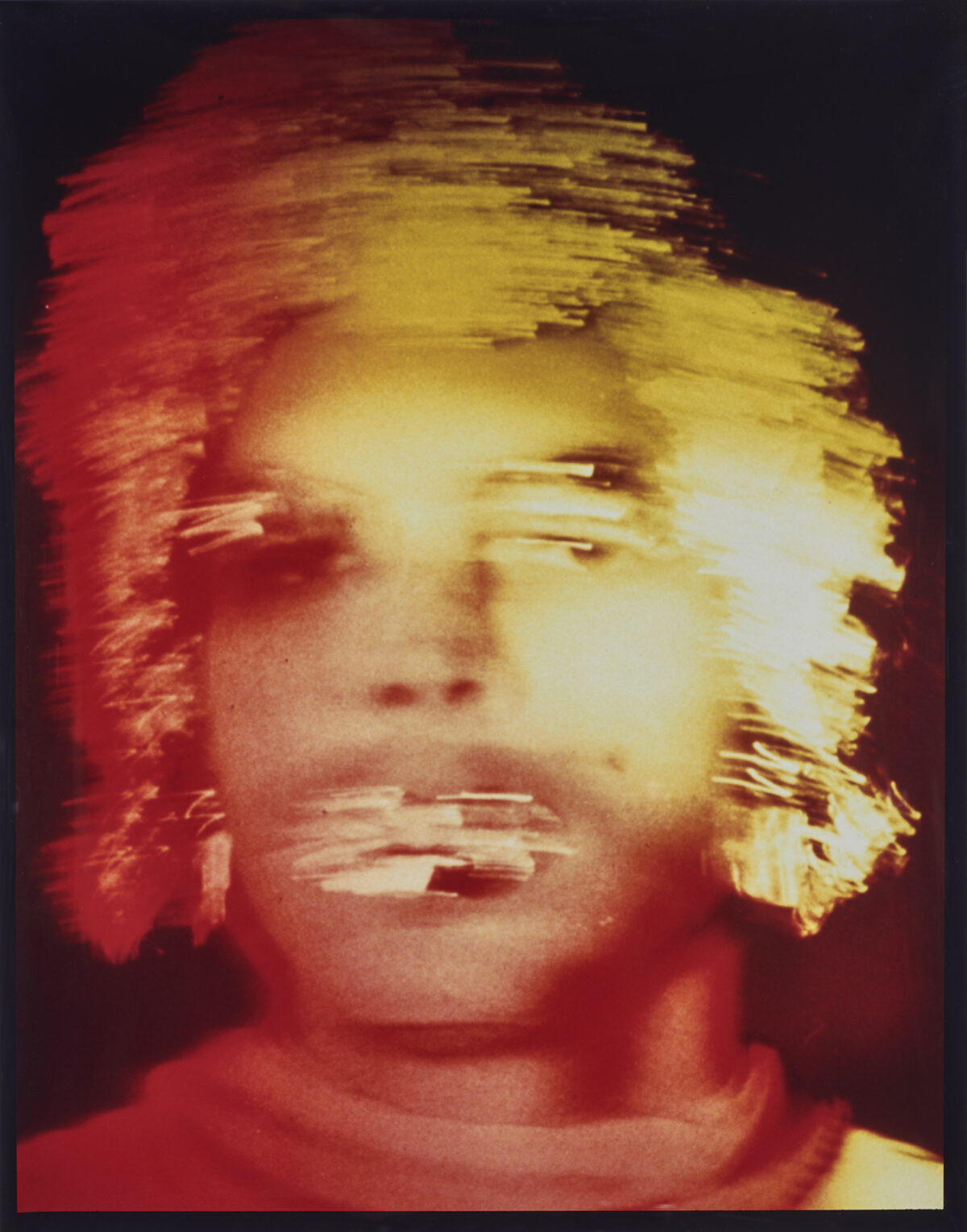

Moving to the United States after the fall of Communism, Polish artist Piotr Uklánski found a timely muse in the shape of Eastman Kodak’s The Joy of Photography, a how-to guide that coincidentally indexes the popular American taste of the era. In his 1997–2007 series of the same title, Uklánski plundered the book’s clichéd imagery en route to a tongue-in-cheek exploration of the medium and its meanings. Multiple entries in the series—in which the artist remade stock scenes for the camera—form the backbone of this flawed but fascinating survey of his photographic oeuvre.

Aspects of the exhibition, on view at the Met through August 16, feel constrained: The Nazis (1998), Uklánski’s unforgettable rogues gallery of uniformed bad guys from cinema and TV, is shown in an abbreviated version. There’s also a lapse in thematic logic in the shape of an elephantine fiber art sculpture, Untitled (Story of the Eye) (2013), the only non-photographic work in this section of the show. Gratifyingly, though, Fatal Attraction also includes two additional components housed in separate spaces in the Met, the first being an array of works selected by the artist from the museum’s collection. Plainly, Uklánski got carried away. He picked out works by everyone from Lucas Cranach to Laurie Simmons, articulating the intersection of corporeal beauty and horror, but the abundance of works overwhelms the space.

The second, more successfully sited addition to Fatal Attraction’s main display is suspended overhead in the museum’s entrance hall. Uklánski’s Untitled (Solidarnosc) (2007) is a pair of large photographic banners. One depicts three thousand Polish soldiers arranged into the shape of the logo of the pioneering non-Communist labor union; the second shows the same scene, shot in the Gdansk shipyard where Solidarity was founded, but as the participants begin to drift away from their places and the logo starts to dissolve. It’s a pointed critique of personal-political groupthink that gains immediacy from its bustling context.