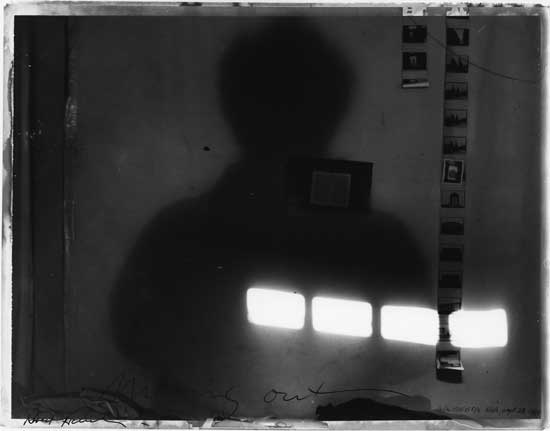

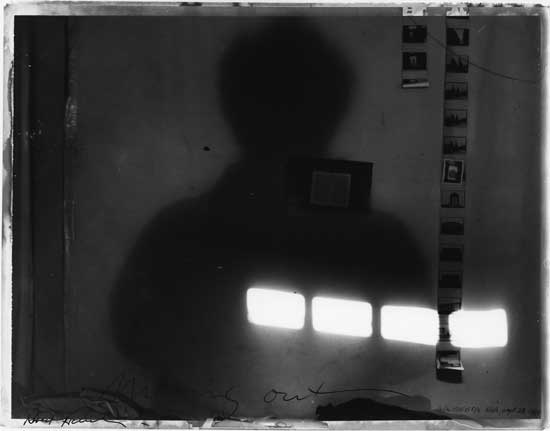

When Robert Frank died on September 9, at the age of 94, he left behind his wife, June Leaf, many friends and admirers, and countless photographers who were profoundly influenced by his work. His groundbreaking 1959 book The Americans – a work of social criticism imbued with enormous empathy – changed the course of American photography, but his films and his later, more autobiographical, photographs were deeply meaningful as well. photograph invited several photographers to comment on what Robert Frank meant to them.

ALEC SOTH: As I write this, I’m driving cross-country and am in Detroit, the location of a number of Robert Frank’s classic photographs from The Americans. No matter where I go I feel his influence. It’s like I’ve been in an imaginary conversation with him for decades. I was too in awe of Frank to seek out a real conversation. He once sat behind me at a fundraiser where I refrained from introducing myself. I didn’t want to clumsily try to express how much his work meant to me. But I’m positive I wouldn’t be here in Detroit – on the road with eyes wide open – without his having paved the way.

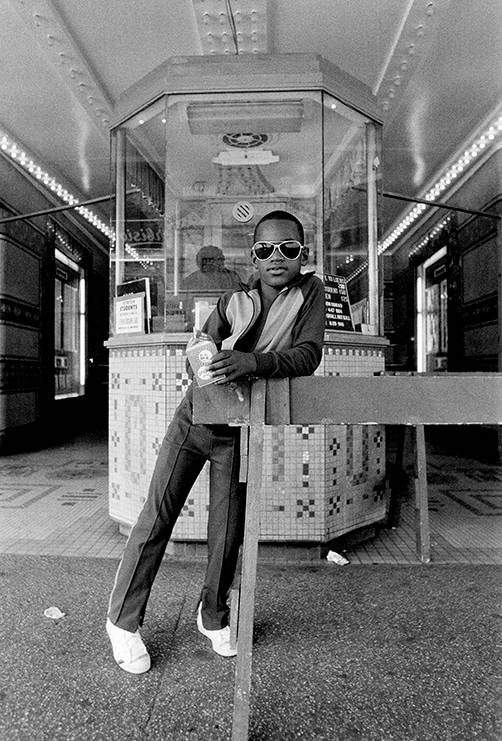

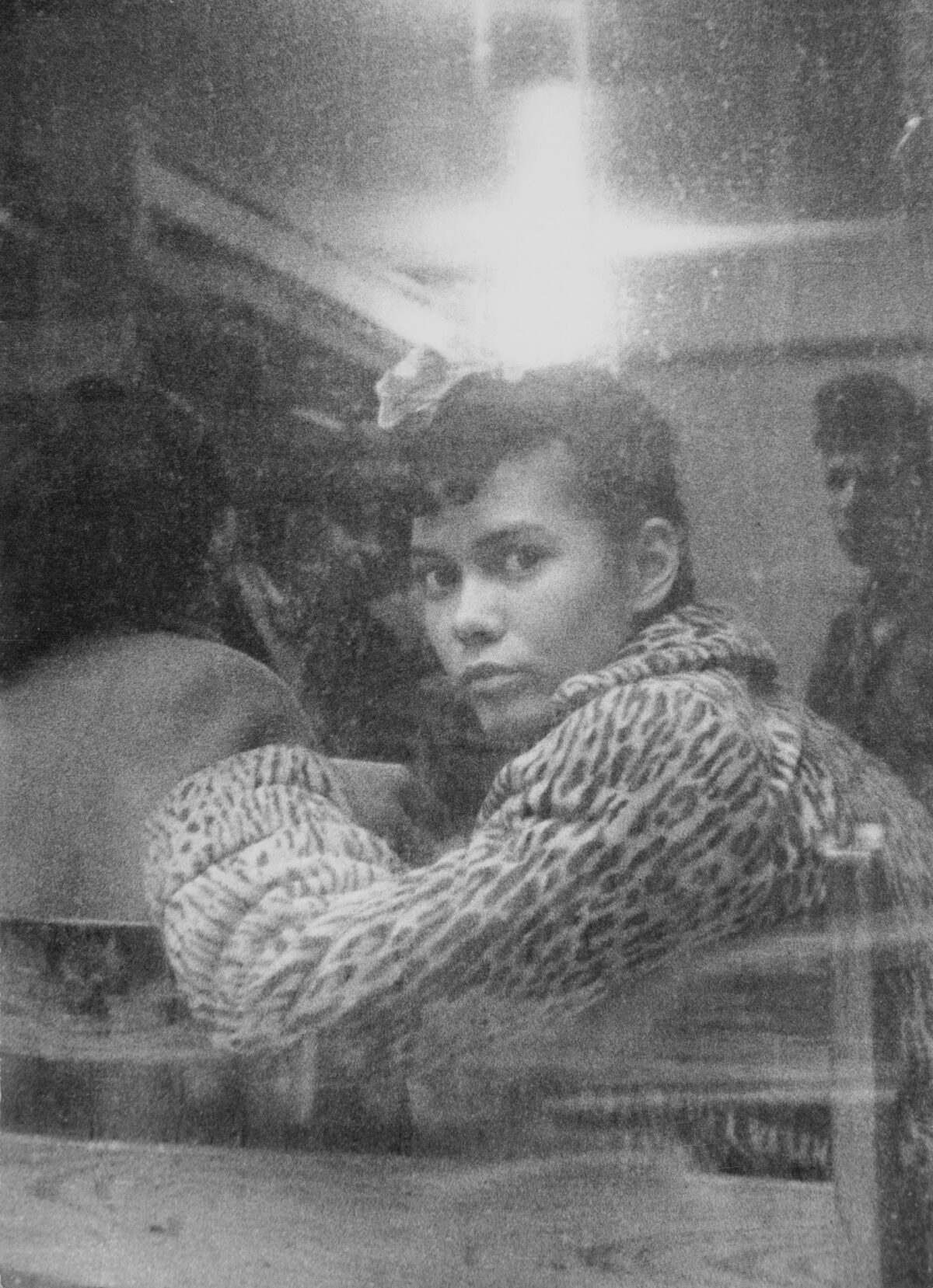

CHESTER HIGGINS: Robert Frank brought a freshness, in the 1950s, to the way Americans are seen. Mr. Frank departed from the usual power dynamics visualized by white photographers when making images of people of color; in his photographs, I saw for the first time African Americans portrayed by a white photographer in the fullness of themselves. Refreshingly, Frank’s work is free of the deep-seated cultural baggage that so often nullifies the humanity and dignity of people of color. His work confirmed for me that a photograph never lies about the photographer.

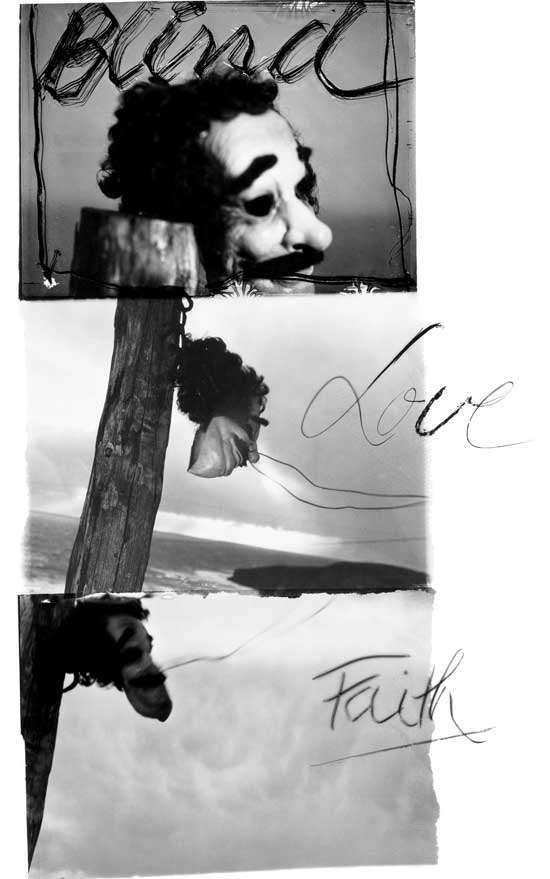

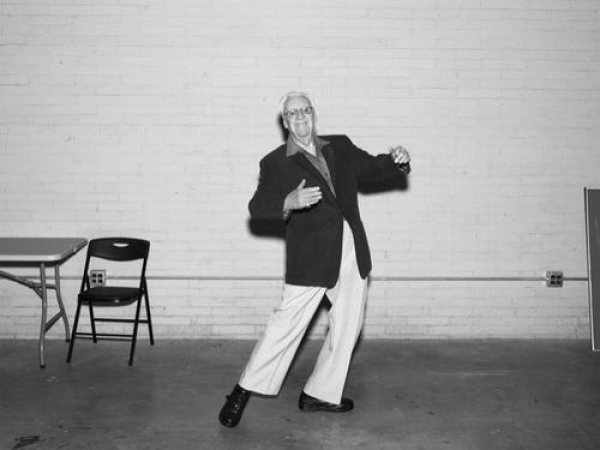

DAWOUD BEY: Robert Frank had the audacity to change the way photographs were made. Using a small handheld camera, he came to America from Switzerland and saw an America that the country itself did not always want to see. His piercing vision, critical mind, and razor sharp reflexes found him over and over again visualizing a place of social turmoil and tension, and occasionally poetic beauty. Photographs were not made, read, or thought about the same way after Robert Frank’s The Americans was published. It constituted a new beginning, a new and more incisively improvisational way of using the small camera in the streets to talk about the social world around us. If that was all he did, his profound place in the history of this medium would be secure. But, like the best and most ambitious artists, Frank was always looking for his next expressive mode, having no interest in turning into his own oldies show. His later works and films show a restlessness and ambition that any artist or photographer should pay serious attention to, as they suggest very powerfully that there always has to be a “next thing” in the creative and expressive process. Through his big heart and his brilliant mind and eye, Robert Frank created an enduring and indelible path. We would do well as artists to consider following him.

CURRAN HATLEBERG: I saw The Americans for the first time in Colorado, when I had just failed out of college. It was a passing glance, really. As I paged through the book, the snow fell heavily outside. The pictures left little impression on my mind at first. Then, I stopped on a photograph of a woman. Beaufort, South Carolina. She sits surrounded by fields, laughing. It is deep summer, and the sun almost rests on her shoulder as it sets. I paused. Then, I closed the book – late for work – and I didn’t open it again for years. Though it’s not my favorite of Frank’s pictures now, it was the first that held my attention, and I wonder what it was that mesmerized me all those years ago. The ease of her posture? The heat of summer trapped in the frame as the snow piled up? I think about that picture now – everything that makes it so good, so perfect – and I wonder, what did I think about it then? Was I contemplating that woman’s carefree laughter as I hurried to work? Maybe. Or maybe I was just worrying about the time and ice collecting on the road.

WENDY EWALD: In 1959, Robert Frank photographed the Gratiot Drive-In theater on the outskirts of Detroit. I was eight years old. In the sixties, when I was a teenager, I would take the bus downtown to a movie in Detroit. Then came the Rebellion of ’67. The next summer I volunteered to work in a settlement house near Gratiot, a wide street that ran from the suburbs to the inner city. I went to a movie theater on Gratiot with some friends. Within minutes a fight broke out; the next day, the theater was shut down. I realized that Gratiot was no longer a place where I could be, as it had been for Frank. The only time I met Frank was at a symposium. I was 22 and determined to be a photographer. I’d seen Frank’s photographs and their rawness frightened me. He talked about leaving photography and becoming a filmmaker. I asked him if he was addicted to the struggle and pain of change. He kindly said it was an interesting question. It took me years to understand and relate to Frank’s role as an outsider with a keen, poetic eye. When I look at The Americans it brings me back to a Detroit I lived in. The Gratiot Drive-In and its clusters of parked cars must have seemed exotic to Frank. He could see then what I would understand only in retrospect, 50 years later.

RALPH GIBSON: I met Robert in 1967 at Max’s Kansas City Bar. I asked him to look at my work and he invited me to his apartment the next day. As I was leaving, he said that he wasn’t doing photography any longer but could use some help with his film Me and My Brother…Our friendship had begun. He said, “I might fall flat on my face with this film but at least I am trying to do something original.”

A few months later I was in his car with him driving up Park Avenue. I was complaining about being in love with a girl who definitely was out of my league financially. He said, “The way I see it is you have two choices. You could become successful quite soon commercially or you could do like me and become an artist.” And turning to me he continued, “and you really only have one choice.”

With those words, I stopped showing up at Magnum and abandoned commercial photography.

Thanks forever, Robert.