When a person sees me for the first time, they will notice that I am very creative fashion-wise and personality-wise. I seem girly (which I am), but little do people know I also do “guy” things like skateboard and aggressive in-line. Even though I’m a talkative person, I do take time to listen to others. I am known to give great advice and I always look at the bigger picture and think critically toward every situation. Because of that I think psychology would be a great field for me in the future. When people first see me they think I’m very quiet and sometimes a little intimidating because I look serious (because I think a lot), but once I get to know people, I can be a lot of fun. My bubbly attitude wins people over. —Ziarra

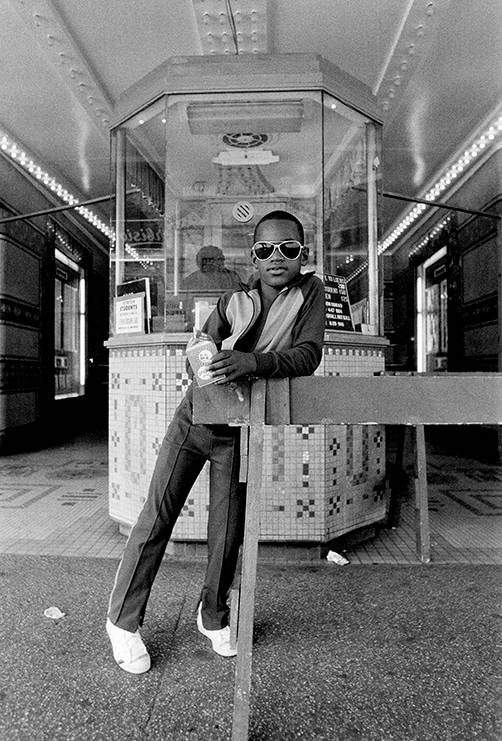

Every photographer is haunted by what lies outside the frame, by the dense reality that flows around the picture and mocks its spurious, truncated truth. The portraitist Dawoud Bey is especially sensitive to that “other information,” as he calls it. Can a single image tell us if a person has a family or has lost a loved one, if he loves playing the baritone horn or she can speak four languages? In the case of teenagers, who are just starting out in life and may not yet have registered disappointments and successes, a portrait may tell us even less. Bey wanted the portraits he was taking to tell us more, so he conceived the project Class Pictures, on view at the Aperture Gallery in Chelsea from January 10 to February 28 and published in a new Aperture book. Each image is presented with a text written by his subject: composed, importantly, before the picture is taken. “Hopefully,” says Bey, “the two add up to something more complex than either of them would be alone.” Yet perhaps Bey places too little trust in the intuition of the photographer and his 4 x 5-in. view camera. Is it so surprising that Ziarra, who looks at us with enormous, penetrating eyes, yet half hidden behind her hair, should insist, in her text, on the difference between what you see and what you get—an outgoing person who is also reflective, a serious person who is also fun to be with? Bey has placed her by a row of lockers, with one lock prominent in the foreground. Can the metaphor be only a happy accident? “The pictures are staged but with a credible narrative of personhood,” he says. “I want the viewer to be left with a seemingly unmediated experience of another human being.” These class pictures are, after all, complex artistic collaborations between seer and seen. That is what interested Diana Edkins, Aperture’s director of exhibitions. “There is not an element of Dawoud’s images that he is not aware of,” she says, “and what’s around the subjects is just as important as how they present themselves in revealing something of who they are.” Teenagers have become Bey’s signature subject over the last two decades, and Edkins’s remark hints at what drives the artist. His young people come from schools in seven different cities and from a variety of backgrounds. In every case, they defy categorization and, of course, the stereotypes that go with them. “Neither race, class, nor gender explain or situate the individual,” he says. As for those who make up the genus American teenager, Bey has done them the greatest possible service, taking them seriously without patronizing or promoting them. In this, he follows the line of August Sander, cataloguer of 1920s German society, who sought to reconcile the particularity of the individual with the typicality of the group. Photography may conceal truth by framing the world, but it resists falsehood by drawing our attention to the visible. For Bey, that is the medium’s saving grace. We create categories, but the camera confounds them.