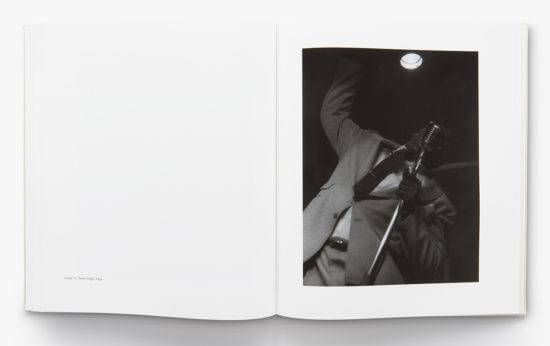

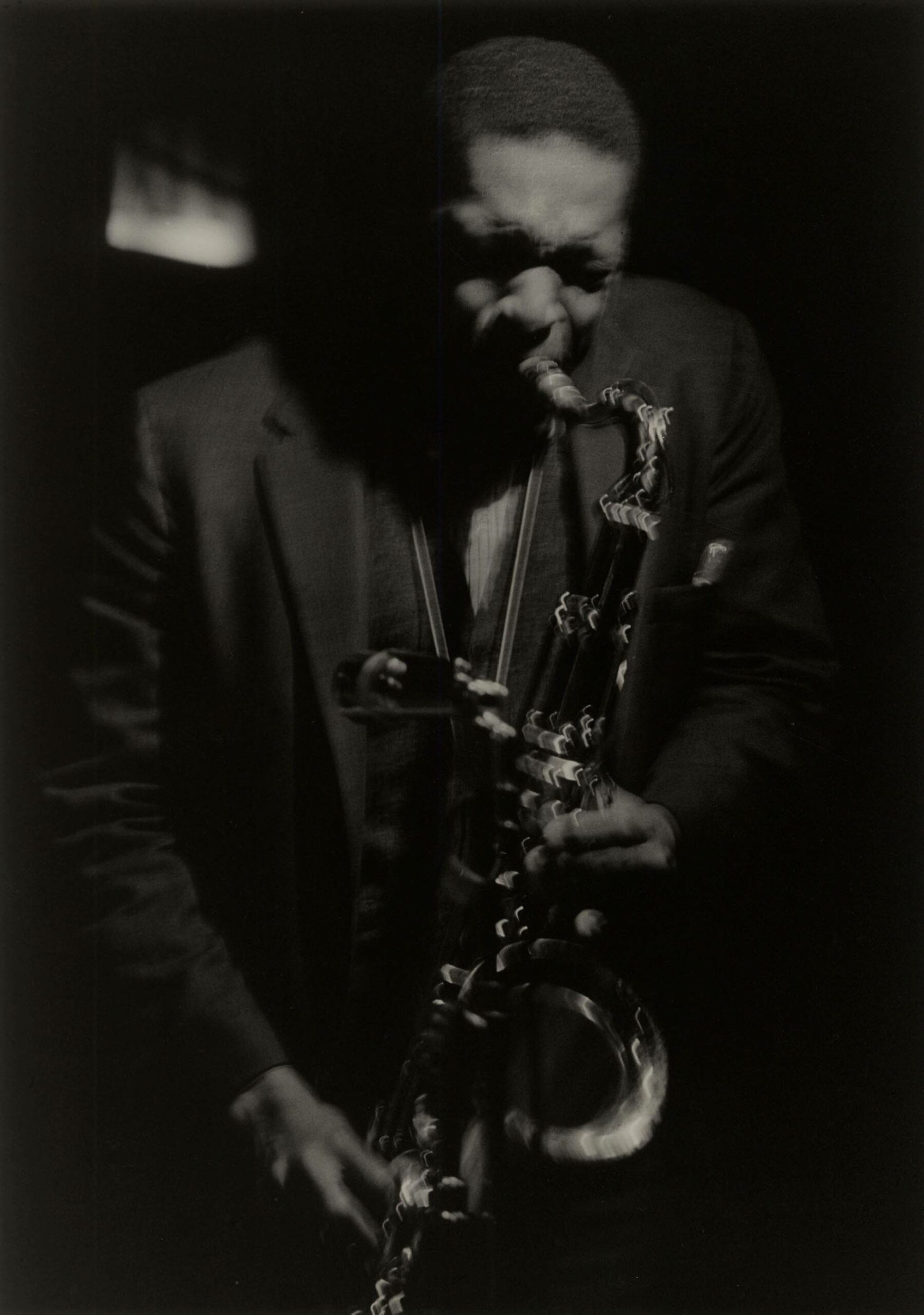

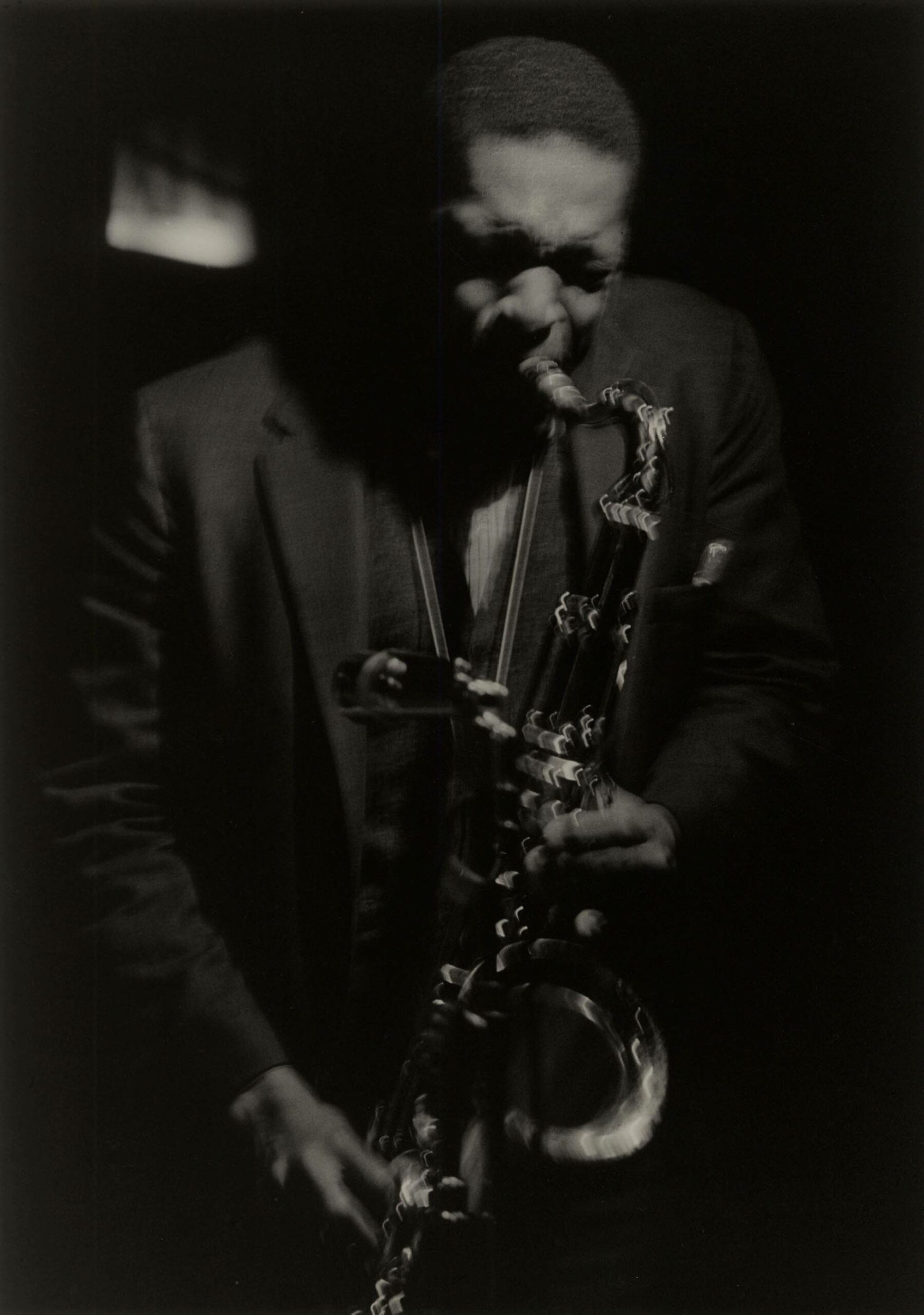

David Zwirner Gallery offers two opportunities to explore the work of photographer Roy DeCarava this fall, on view through October 26. Together they constituted a museum-quality retrospective, the most important presentation since the Museum of Modern Art’s 1996 exhibition. Zwirner’s uptown location presented DeCarava’s photographs of the jazz milieu, most of them well known by now from his published volume (reprinted in a new edition from the gallery) the sound i saw. These are wonderful pictures – moody, intense, and laden with nostalgia. At least a dozen are among the best portraits ever made of musicians at work (or artists, for that matter).

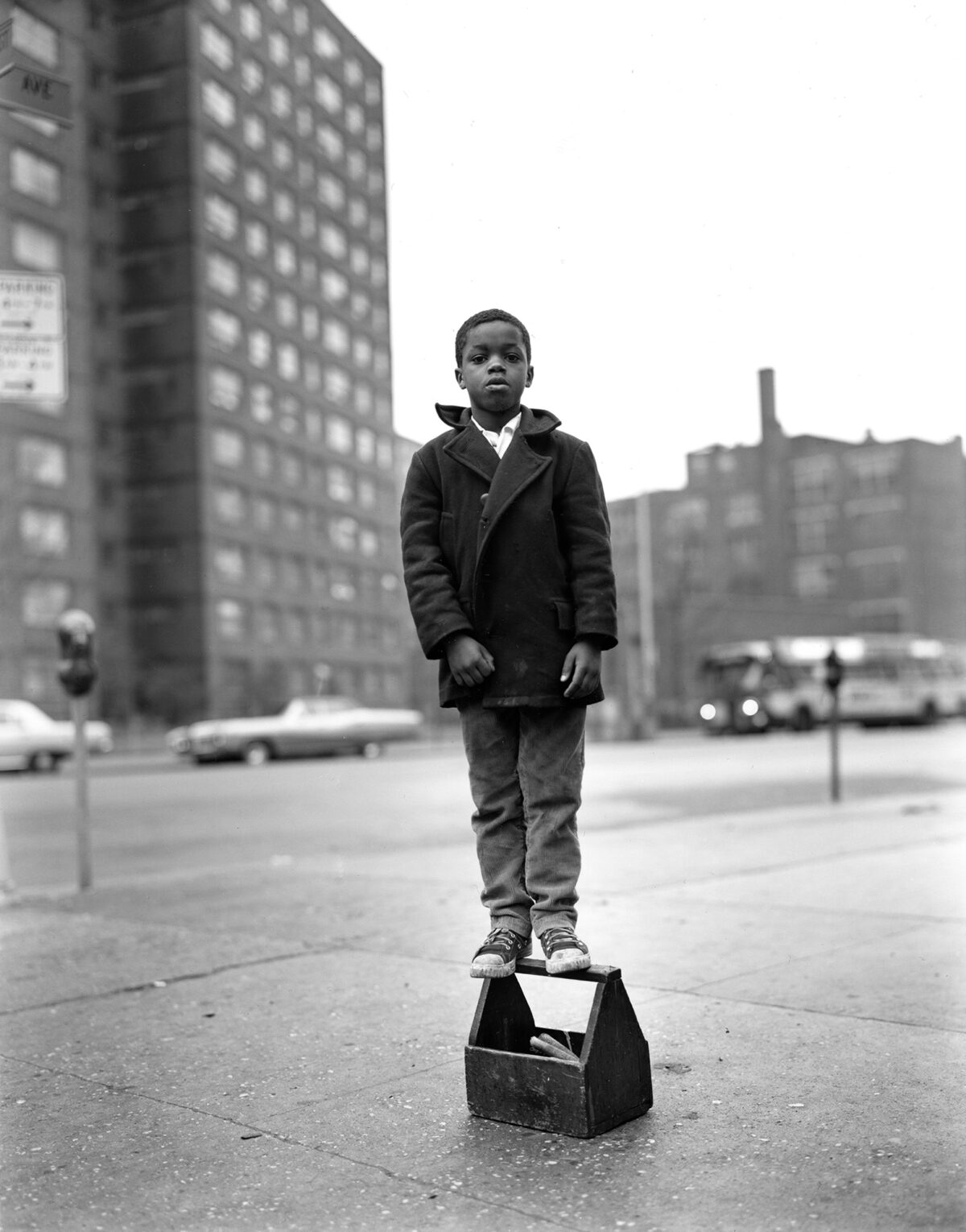

The selection at the Chelsea gallery, titled Light Break, was another story. Curated by the late photographer’s wife, the art historian Sherry Turner DeCarava, the selection of vintage prints from the DeCarava archive took a positioned stance. Her DeCarava is a dyed-in-the-wool formalist and a creature of the darkroom, a master of the architecture of the black-and-white image, seeing every situation as an occasion to compose – just like the great jazz musicians he loved to photograph. The chronicler of the Harlem streets, the collaborator with poet Langston Hughes on The Sweet Flypaper of Life, the premier thematizer (along with Gordon Parks) of American racial identity here recedes in the face of broader expressive preoccupations: the solitude of individuals, the luminosity of specific moments, and the revelatory power of darkness. In his titles, DeCarava emphasized the formalism of his seeing. An apparitional image of an automobile in profile, for example, is titled simply White Car and Dots, 1961, those dots being points of reflected light. Catsup Bottles, Table and Coat, 1952, betrays its deepest affiliation with the tradition of still life painting, right up through Giorgio Morandi. This is the DeCarava who opened a pioneering photo gallery in 1955 to champion photography as a modern art, not as a form of social engagement. His aesthetic attention to the darkroom print was further emphasized by his decision to shoot most of his photographs in low light. His most autobiographical picture, Hallway, 1953, is so dark it is more imagined than seen, and that was the point of an expressive art. DeCarava’s prints are an exploration of midtones. In the vast white spaces of Zwirner, they first seemed overwhelmed, but their darkness took dominion everywhere. Visitors peered into the rectangles of dim light, waiting for their eyes to adjust. You could have heard a pin drop.

In a time preoccupied with the relativity of all experience, especially identity, contemporary theorists will ignore the deeper possibility, not voiced by the photographer, that race is inscribed in the very tone of each print. They will likely label this show depoliticized. Meanwhile, a younger generation of photographers, working their way past nostalgia and seeking to understand what might still be communicated through black-and-white photography, will begin here, just at the boundary where light ends and dark begins.