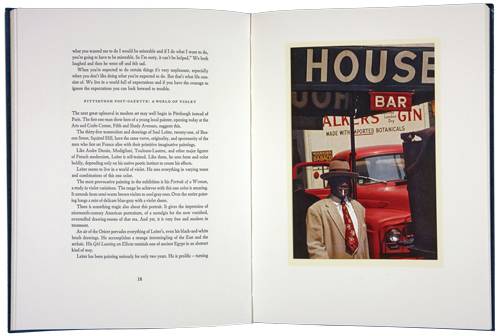

Photography, the medium that began life as unflinching witness to the world, has long delighted in flexing its muscles in unexpected ways. This vibrant show by Venetian-born, UK-based photographer Lorenzo Vitturi presses it into ever-more supple positions: allowing it to function both as discrete, collectible art object and chameleon-like supporting character actor within a larger mise-en-scene. The result is this delightful, immersive show, on view at Yossi Milo through January 10, full of juicy color and formal rhythms, even as it takes on larger issues like identity, the conceptual limitations of portraiture, and class.

Every aspect of Milo’s white-box gallery space was pressed into service here: its cement columns festooned with such raucous detritus as striped tarp, plastic vegetable packing material, a coconut resting on a homemade shelf, and powdered pigment. Vitturi’s subject matter is the open-air Dalston Ridley Road market in East London. Its vendors are primarily of Caribbean and African descent, and the market is facing the threat of gentrification. You feel him thoroughly delighted by the many sights, smells, and sounds of the place as he takes the fruits and vegetables sold there back to his studio, where he pins them into anthropomorphic positions and photographs them before their eventual decay: nubbly brown breadfruit poked with wooden hair combs; an over-ripe banana supporting limbs of pale green berries and tomatoes. In the marketplace, all good things eventually rot and come to an end, so there’s more than a bit of the Vanitas in these exuberant constructions as well the weird humor of Archimboldo.

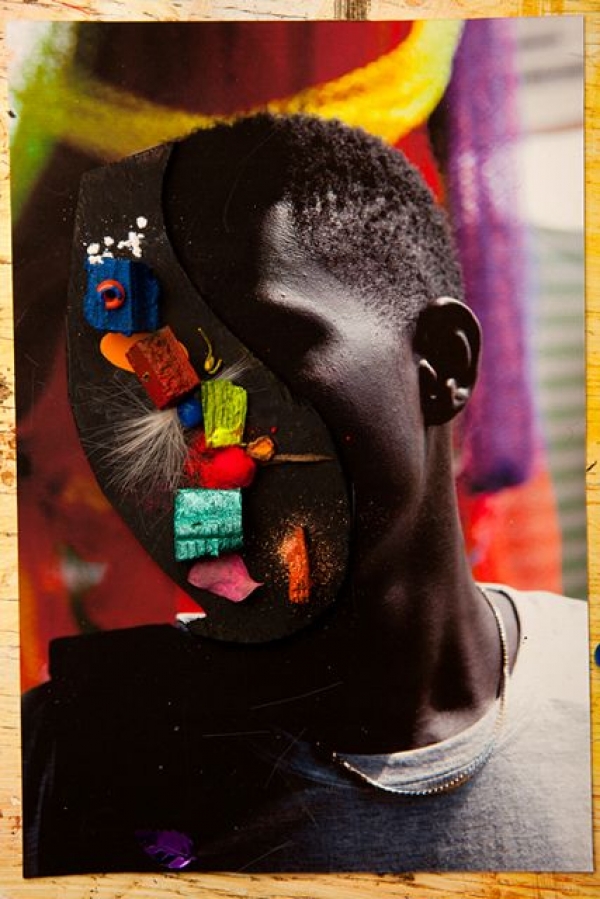

As for his more straight photographic portraits of people in the market, what the artist chooses to leave out is as interesting as what he depicts. More than 75 percent of the “portraits” here obscure their subject’s faces, blotting out one woman’s face with a dusting of bright yellow chalk; covering another man’s features with a scattering of tiny, sewing-drawer-type notions in a tutti-fruity palette. Exact identities are a mystery, but textures like clothing and jewelry and skin color are intact, forcing us to question how much we think we know about the inner life of people who come from worlds more seemingly exotic than our own.

At first, learning that Vitturi is Venetian is almost startling. One senses how deeply he must have had to earn his sitters’ trust in order to involve them in an experiment so aestheticized without exploiting them. On further consideration, Venice is a romantic island culture we’ve all visited and think we know — though we seldom befriend an indigenous resident. Co-option comes in many forms. And Vitturi certainly understands the beauty in decay.