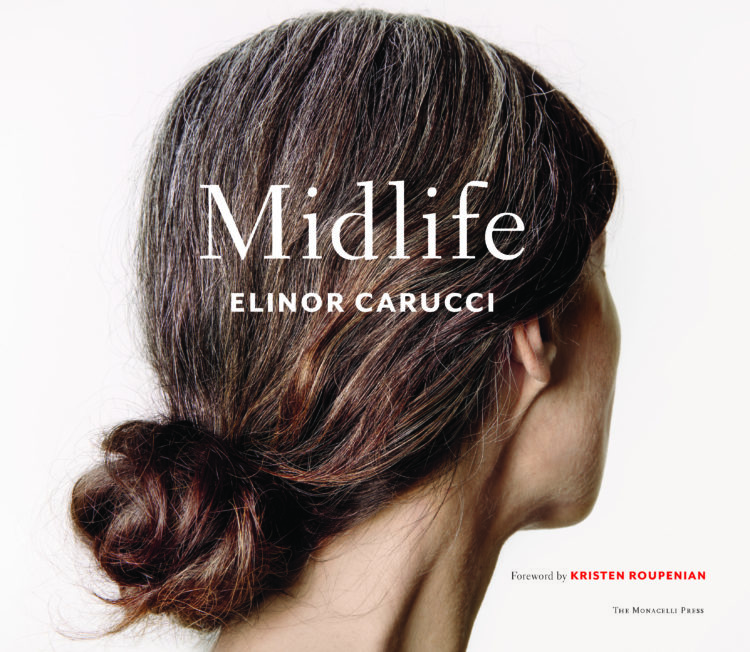

With her first book, 2002’s Closer (Chronicle Books), Elinor Carucci brought us into her life and took us into her confidence, trusting viewers to understand that a certain amount of nakedness, both physical and emotional, was no big deal in her extended family. Closer was an intimate self-portrait with a tight-knit supporting cast, including Carucci’s husband, parents, grandparents, and, from their birth, her children, fraternal twins. Her approach, a mix of cinéma verité immediacy and theatrical staging, with nods to Sally Mann and Nan Goldin, was as nervy as it was sensitive. In her introduction, Carucci wrote that “the camera was…both a way to get close, and to break free. It was a testimony to independence as well as a new way to relate.” She continues that invigorating, illuminating push and pull in her new book, Midlife (Monacelli), combining it with what she describes in the book’s afterword as “a particular, very up-close – almost scientific – way of seeing.” The result is fascinatingly forensic, especially when the subject is her own body, every wrinkle and grey hair of which she examines in near-microscopic detail. Carucci, who turned 48 this year, looks at her aging anatomy and her changing life over the last half decade with more humor than dread, but she’s frank about what she thinks of as her “losses.” She makes a list of them following a hysterectomy in 2015, memorialized in the book’s most shockingly matter-of-fact image: her uterus, looking like a mess of raw meat on a cloth-covered hospital table. If the operation represented “the final loss of youth,” she has others to tick off: “of being productive, being needed as a mother, being attractive, being visible, being relevant.”

Happily, this note of self-pity is flatly contradicted by most of the photographs here.

Carucci is a vivid presence and her family, however reluctant or disgruntled (see Mother Is Mad), is right there with her. She dealt with parenthood in a previous book (Mother, Prestel, 2013), but her children and her parents are still very much a part of the satisfactions and anxieties of her midlife chronicle. And her husband, Eran, remains a steadying force. In one of several images that hark back to Closer, the couple lay naked and side-by-side in bed, Elinor in the foreground, Eran peering at us from behind the crook of her neck. But instead of looking away, contented and abstracted, as she did in 1998, Elinor has turned her head to look out at us, too, with an expression that’s older, wiser, and slightly ironic. Life goes on. And on.

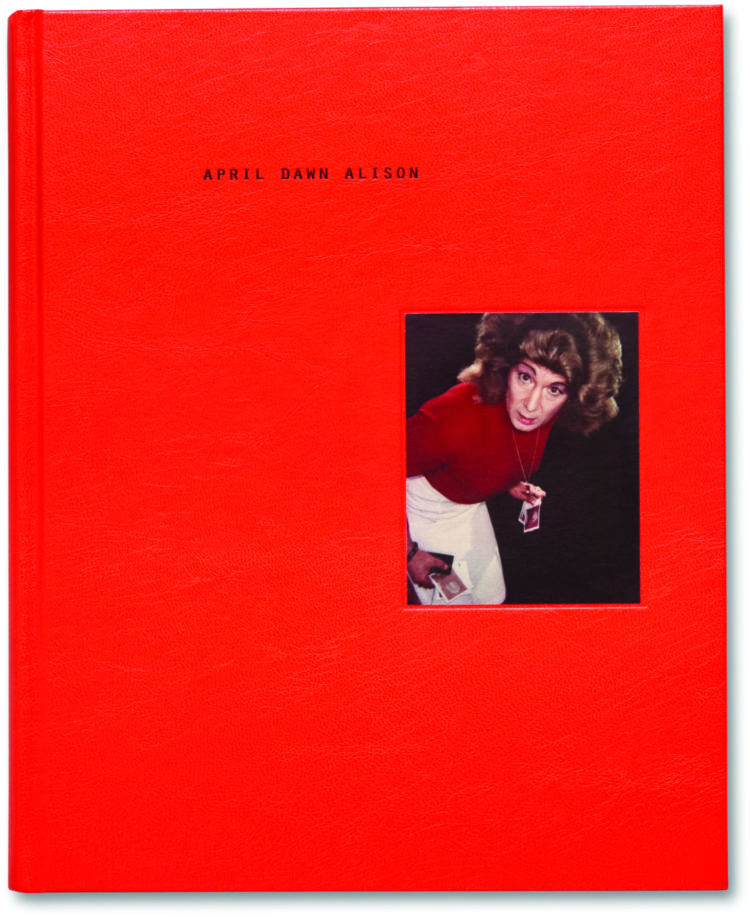

I wonder if midlife held any special terrors for April Dawn Alison, the subject of a new book from MACK. The alter ego of a cross-dressing Oakland, CA, photographer named Alan Schaefer, she seems pretty impervious – a woman who manages to exist outside of passing time. Although he slipped into her clothes regularly, Schaefer kept Alison entirely to himself. The more than 9,200 Polaroids he made of her beginning in the 1970s were only discovered after his death in 2008; more than 350 of them are here and in a show at SFMOMA through December 1. Based on this evidence, Alison had her kinks (bondage, maids’ uniforms) and a tendency toward what curator Erin O’Toole calls “manic exuberance,” yet she often acted like an ordinary housewife or businesswoman, loading the dishwasher, talking on the phone. She was not pretty (she looked like Jimmy Fallon in drag), but she was driven and spirited and would not be held back. She kicked up her heels and showed her panties. Although repressing and unleashing this rude creature over the course of three decades must have taken its toll on Schaefer, she outlives him to astonish, disturb, and tantalize us.