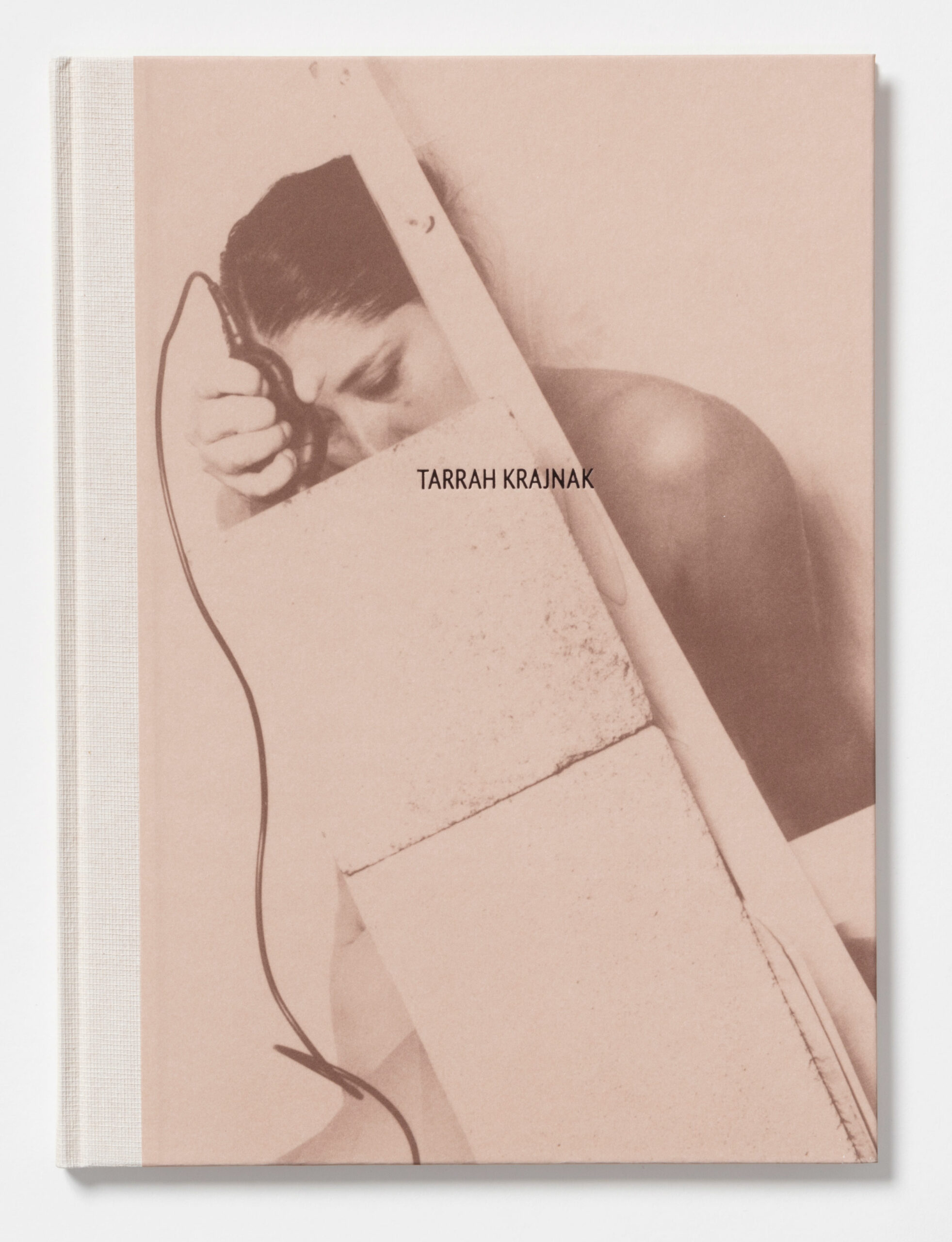

The return of Printed Matter’s New York Art Book Fair in October was a huge event for book makers and book aficionados, who came back together after three years apart like reunited lovers, excited just to be in the same space again. After two frantic, overwhelming, thoroughly enjoyable days, I carried off a stack of books I’m anxious to share, starting with a matched pair of limited editions from the Oakland-based TBW Books. Paul Mpagi Sepuya’s Orifice + Aperture continues his investigation of the studio as a stage and a subject in itself. The photographer and his models are nearly always naked but often seen only in tantalizing bits reflected in or obscured by mirrors and screens. As a result, the work is both frankly and glancingly erotic, full of titillating partial views and at least one startling reveal. Sepuya’s tripod-based camera, and other recording devices held by his subjects, are key players here – spurring, documenting, and staking out the center of the action. Sepuya won’t let us forget that a picture is being made; that doesn’t make it any less marvelous. Tarrah Krajnak’s Master Rituals II: Weston’s Nudes, in an identical (and exceedingly handsome) format, takes a similarly shrewd and clarifying approach to the mechanics of photography. Using her own body, she recreates the poses of Edward Weston’s fragmented, faceless female nudes but makes no attempt to hide the process. Her studio set-ups, including concrete blocks, plywood panels, and a trailing shutter-release cord, are just as naked as she is. Claiming a place in the canon for a woman of color, Krajnak looks right at home; she assumes she belongs there and carries on with her work: an homage and a challenge, both sharp and to the point.

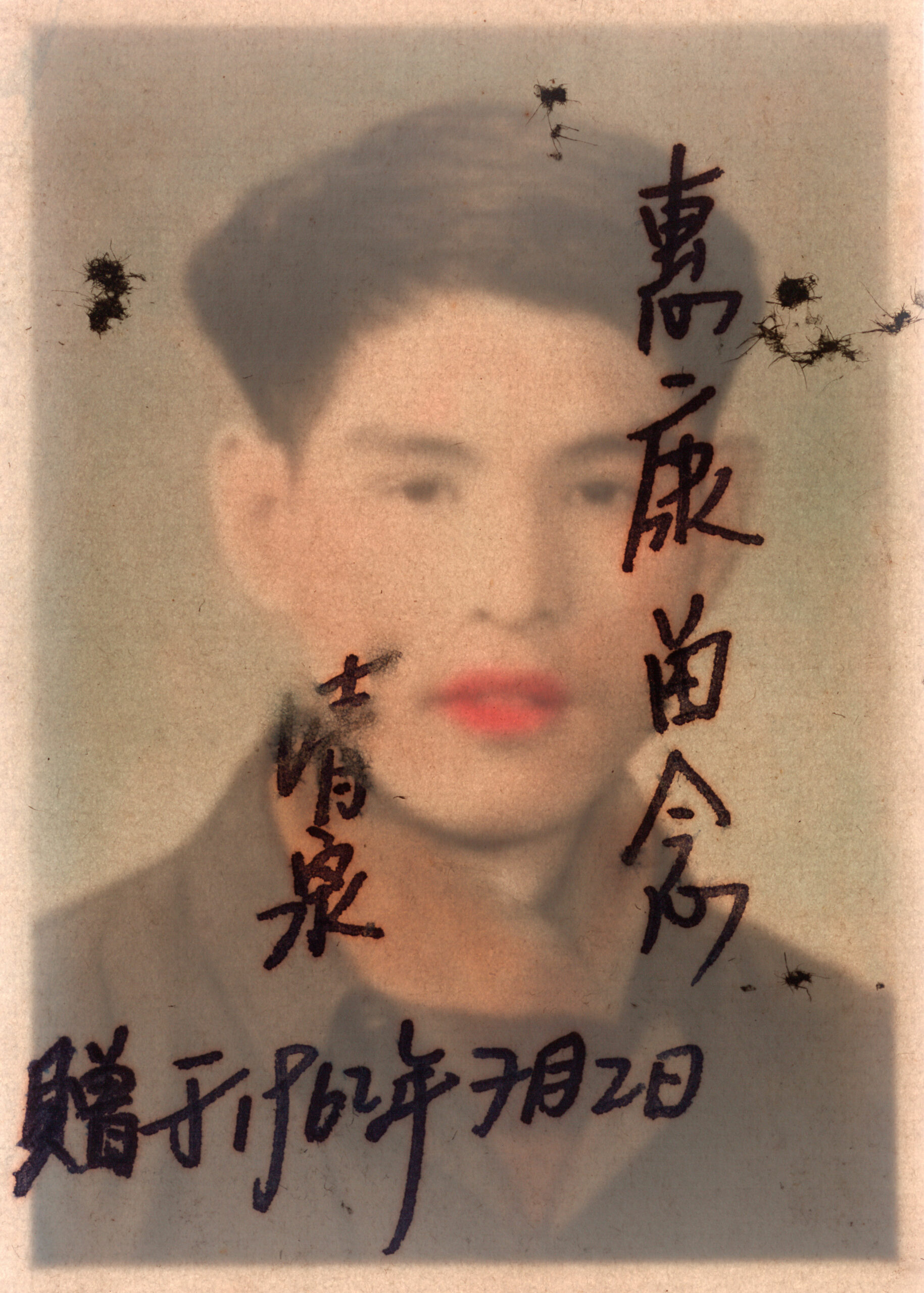

Thomas Sauvin, a French photographer based in Beijing, has been collecting and publishing Chinese vernacular photographic material for some time now, often for London’s voracious Archive of Modern Conflict, the semi-secretive private organization dedicated mostly to the collection and preservation of vernacular photographs, which also organizes exhibitions and publishes photo books. I found two of his books at the fair and am sorry I didn’t discover more. Verso (RVB Books & Jiazazhi Press), a newsprint pamphlet in a gaudy pink and orange binder, compiles a series of generic ID photographs that have been exposed to enough light to render them transparent. The Chinese characters scrawled on their backs bleed through, creating what appear to be double exposures, ID upon ID, but intriguingly hazy and abstracted, like fading memories. 17 18 19 (Void), named after a three-centimeter tag that appears on many of the images, is even more mysterious. Its contents were salvaged from a recycling plant outside Beijing, where negatives from one of the city’s detention centers had been dumped. The images, printed in a silvery, distressed black and white, are dumb evidence, mostly of detainees’ belongings: knives, cassette tapes, coats, portable TVs, playing cards, cash. Even before you get to a short series of mug-shot profiles at the end, echoes of the maniacal documentation undertaken at concentrations camps in Germany, Cambodia, and elsewhere can’t be ignored. But Sauvin also understands the beauty of his found material; despite the corruption and inhumanity of the regimes that produced these images, his books have a haunted elegance.

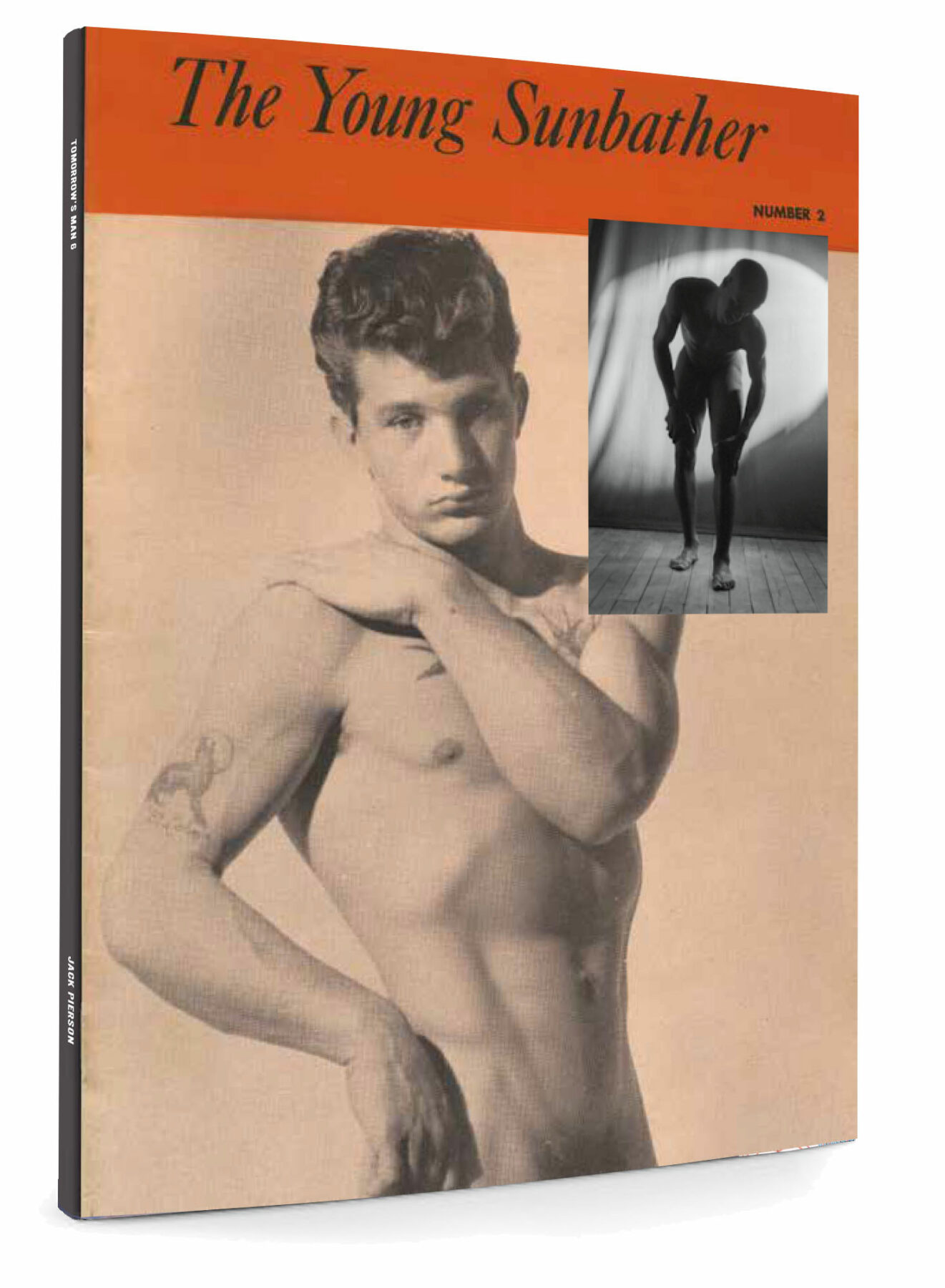

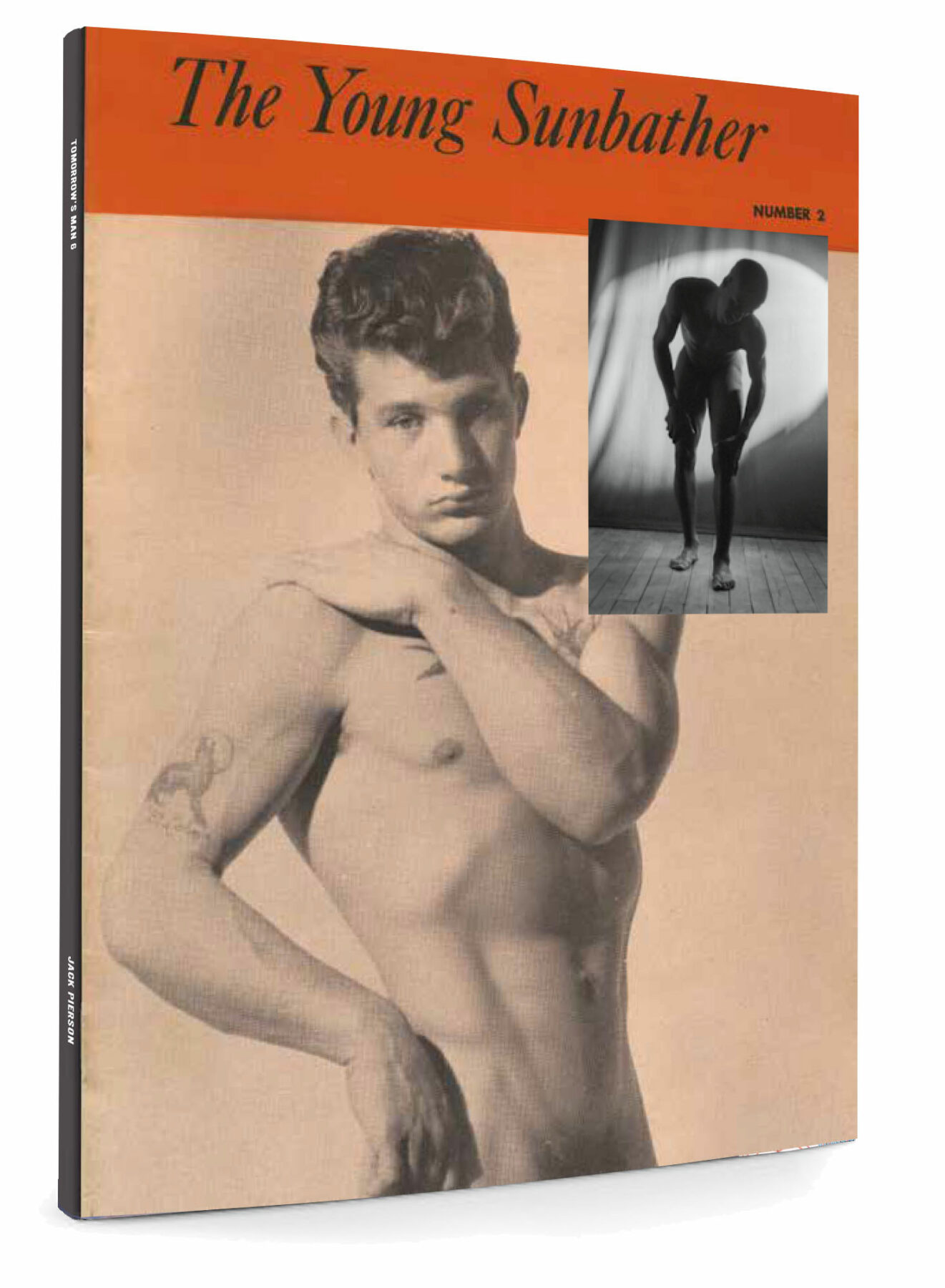

Jack Pierson’s Tomorrow’s Man 6 (Bywater Bros.), the latest entry in an increasingly lively and unpredictable series, mines very different territory. Pierson is just one of 20 contributors whose paintings, sculptures, photographs, collages, and drawings are interspersed and overlapped with a slew of appropriated material in what appears to be a horny, precocious teenager’s scrapbook. The original Tomorrow’s Man was a physique magazine from the 1950s and ’60s, so a playfully retro, post-postmodern aesthetic prevails, along with that period’s idols: Fabian, Ronnie Spector, Little Richard, the Supremes. Pierson’s point of view is the only thing that connects this wildly disparate range of work, so it’s reliably eccentric and packed with fresh discoveries – none captioned, but with a little sleuthing I figured out who made the issue’s understated black-and-white nudes: the French photographer Clement PJ Schneider.

Vince Aletti, formerly a photography critic at the Village Voice and the New Yorker, reviews photography exhibitions and books for the New Yorker’s online Photo Booth feature. His book, Issues: A History of Photography in Fashion Magazines, was published by Phaidon in 2019. The Drawer, a picture book, will come out later this fall from Self Publish, Be Happy, distributed by D.A.P.