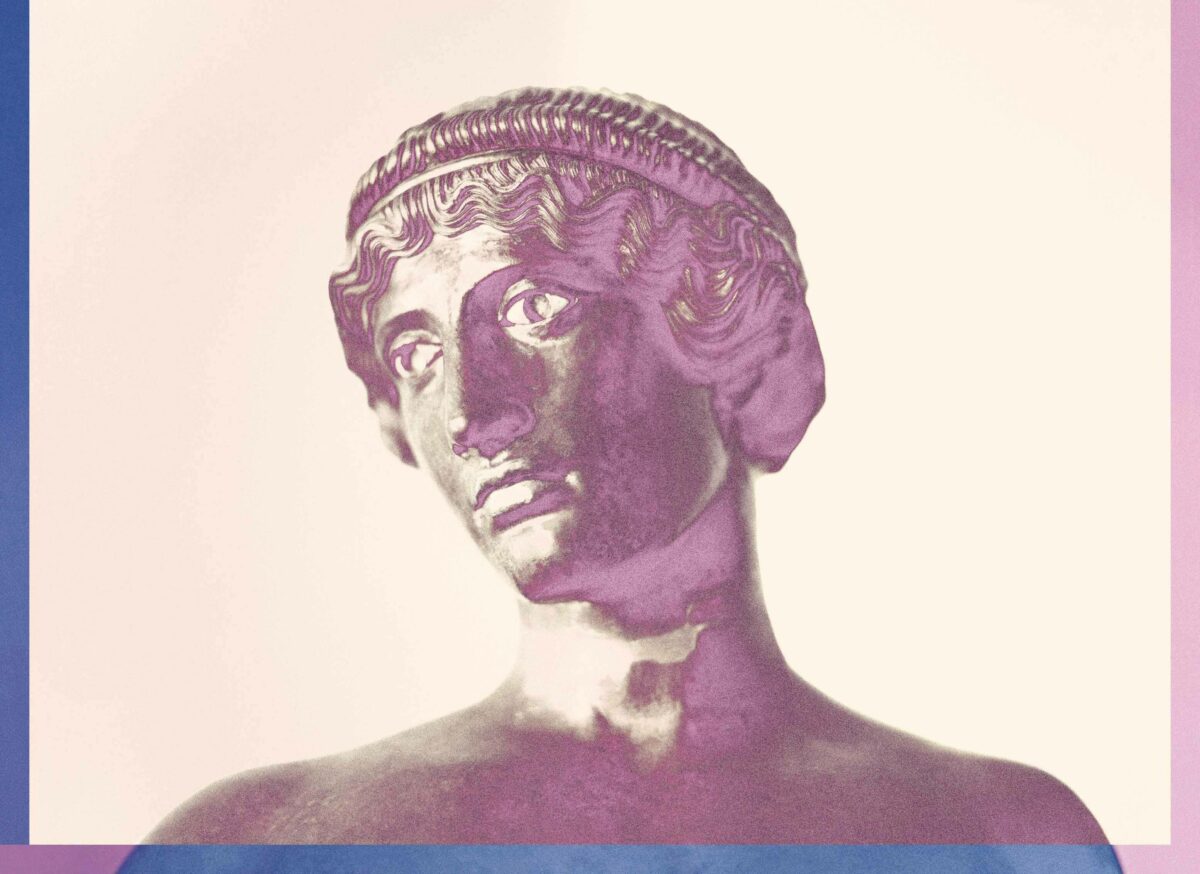

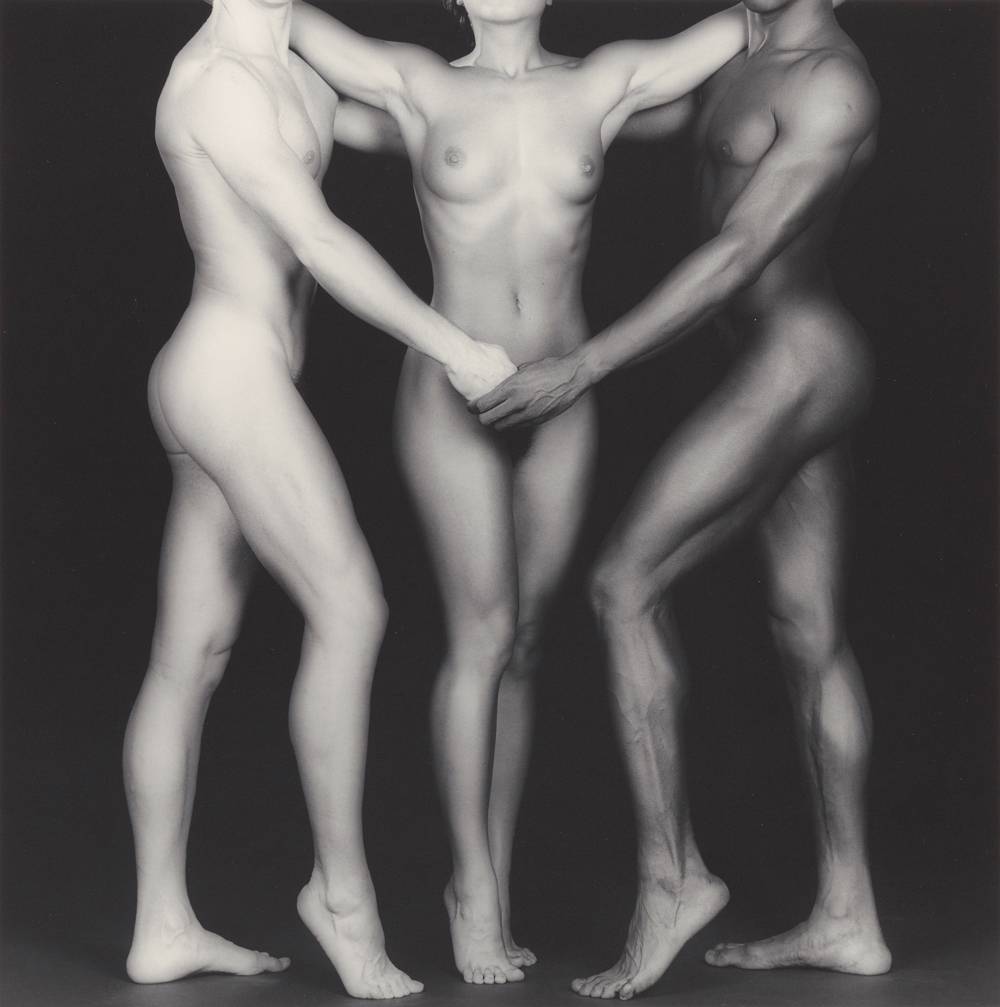

Since he joined The Morgan Library & Museum in 2012, photography curator Joel Smith has assembled a handful of thoughtful exhibitions leading viewers to think more deeply, or differently, about photographs. Beginning with Collective Invention: Photographs at Play, which was as much about the conversations between the images as it was about the individual works, Smith opened up the medium to examine alternate histories and parallel narratives. The new show, a collaboration with the George Eastman Museum, unravels it further still, drawing focus away from the idea of the photograph as a single product to consider it as a multivalent process. Sight Reading: Photography and the Legible World contemplates the way photographs have been used to inventory, to x-ray, and to persuade, among other things.

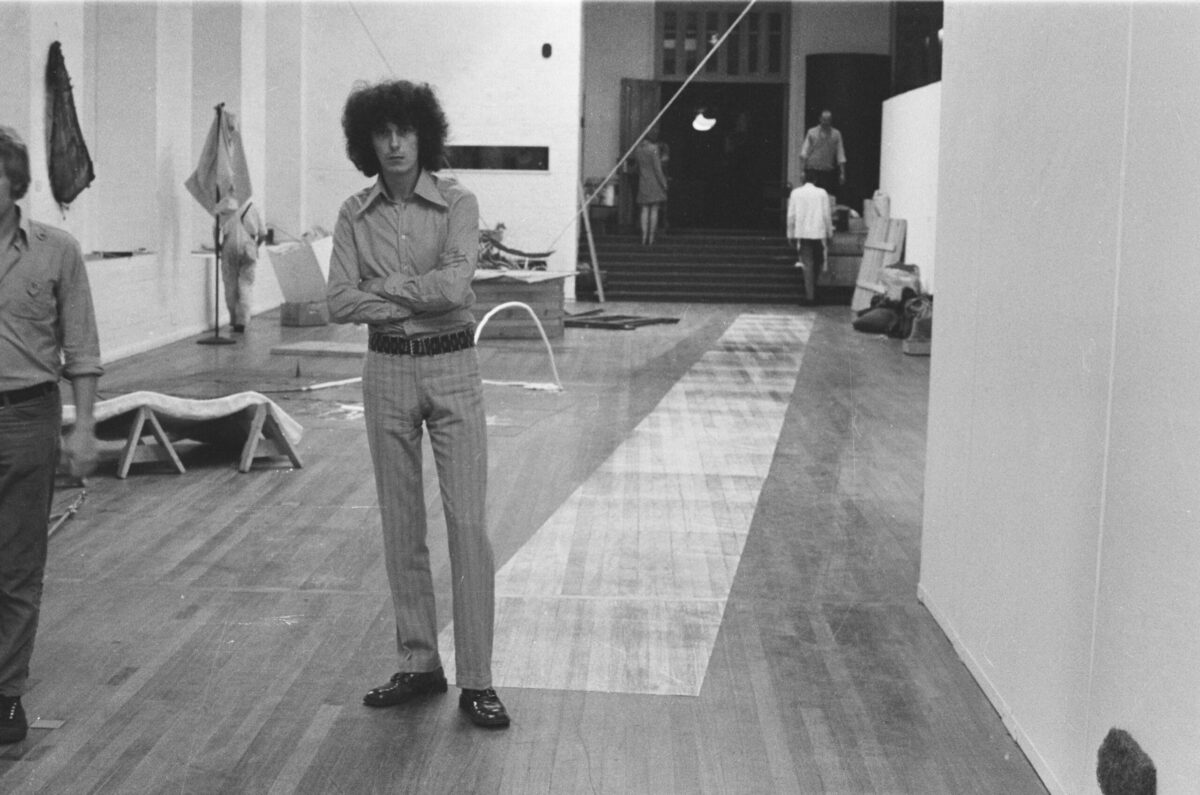

On view through May 30, the show contextualizes more than 80 photographs into nine separate sections (Crafting a Message, The Legible Object, Empire of Signs, for example). For those who have the sense that great images emerge, fully formed and incorruptible, out of the minds of great photographers, it is enlightening to see Lewis Hine’s multiple variations on his iconic image of the mechanic working on a steam pump. The image has been riffed on so many times (including on an album cover for the band Rush) that it’s easy to forget that Hine riffed on it first, printing and cropping it dozens of different ways to convey his message about the importance of labor.

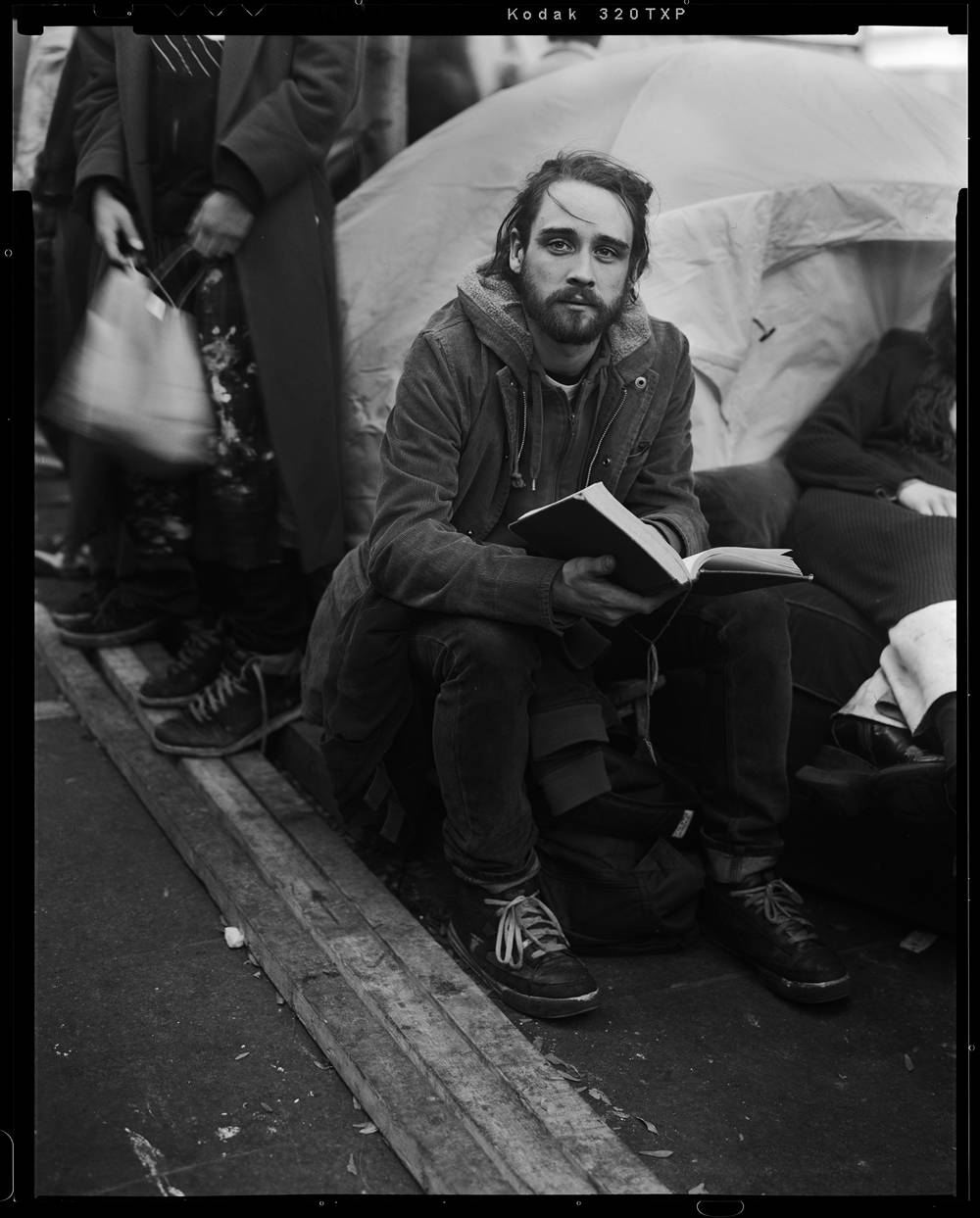

There are great examples of signage on view, like Ferenc Berko’s 1946 black-and-white photograph from Ralwapindi, India, of a man surrounded by Hulk-sized sets of false teeth; and works that amplify the effects of technology, like Jonathan Lewis’s pixelated Beatles album covers, which read like colorful geometric abstractions. Together, the works on view lead us to ponder the way a photograph works – as art, advertisement, diagnostic tool, scientific method, and self-expression. In this age of the selfie, a collection of snapshots, dating from the 1920s to the 1960s, many with delicate scalloped edges, strikes a nostalgic note. Each has a brief handwritten declaration in the margin: “me.” From soldiers sending self-portraits home to a group of young women at a party, beaming into the camera, they all demand recognition, then as now: here I am.