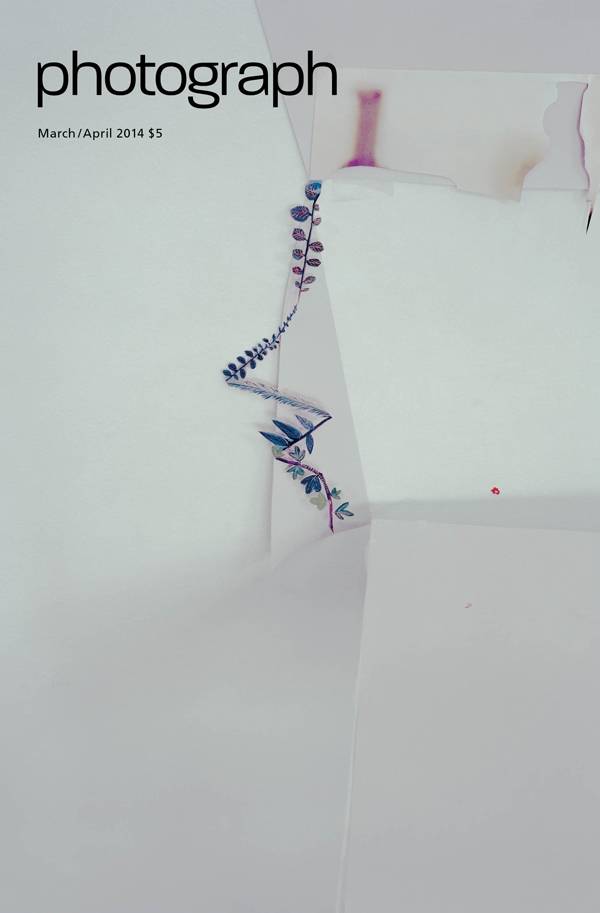

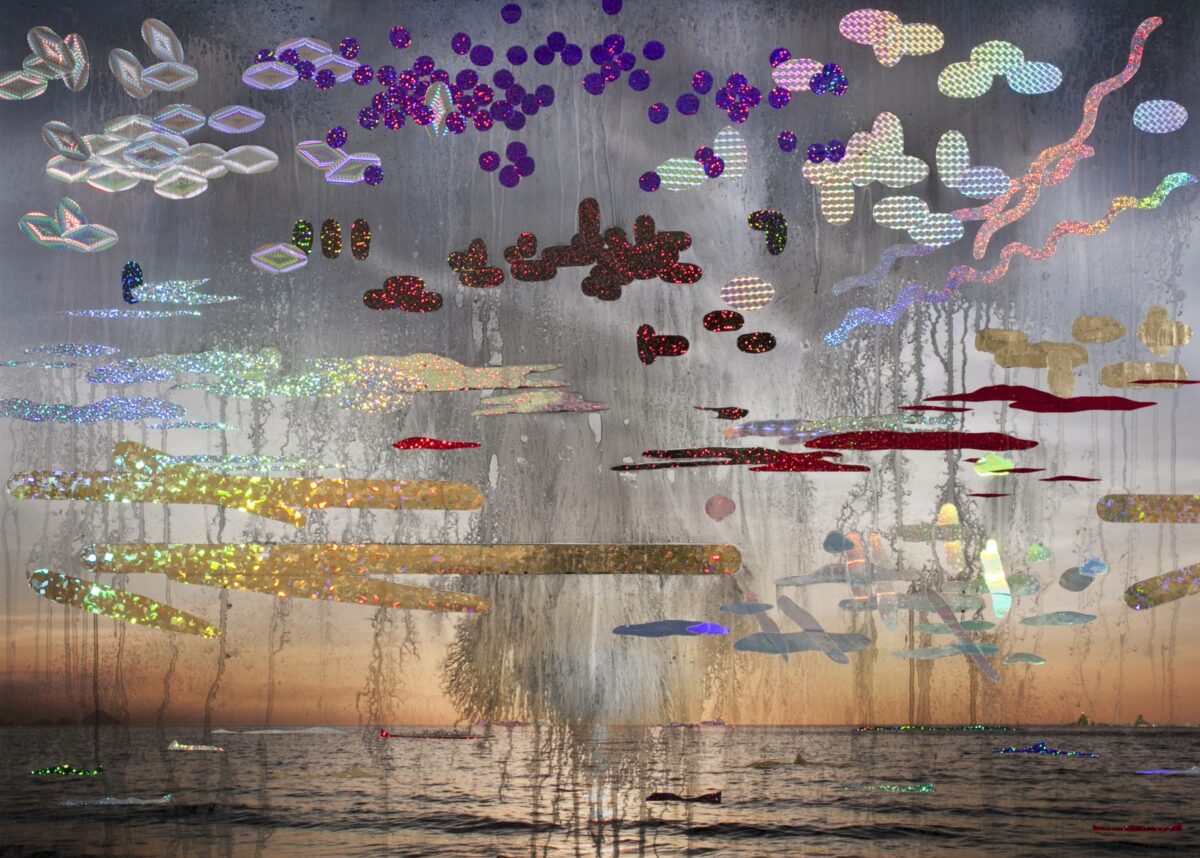

Assaf Evron’s work arrived with all its papers in order: prizes and commissions from Israel, the imprimatur of the Art Institute of Chicago, and a sheaf of art historical references, from Leon Batista Alberti and Albrecht Dürer to Robert Smithson. The installation work looked forward to a time in the near future when photographers will become sculptors and installation artists, working outside the 2D box, and backward to a time when artists were polymathic investigators, combining the study of natural science, philosophy, and optics. The pieces stood out from the wall or occupied the floor, and their connection to photographic roots felt attenuated, sometimes barely perceptible.

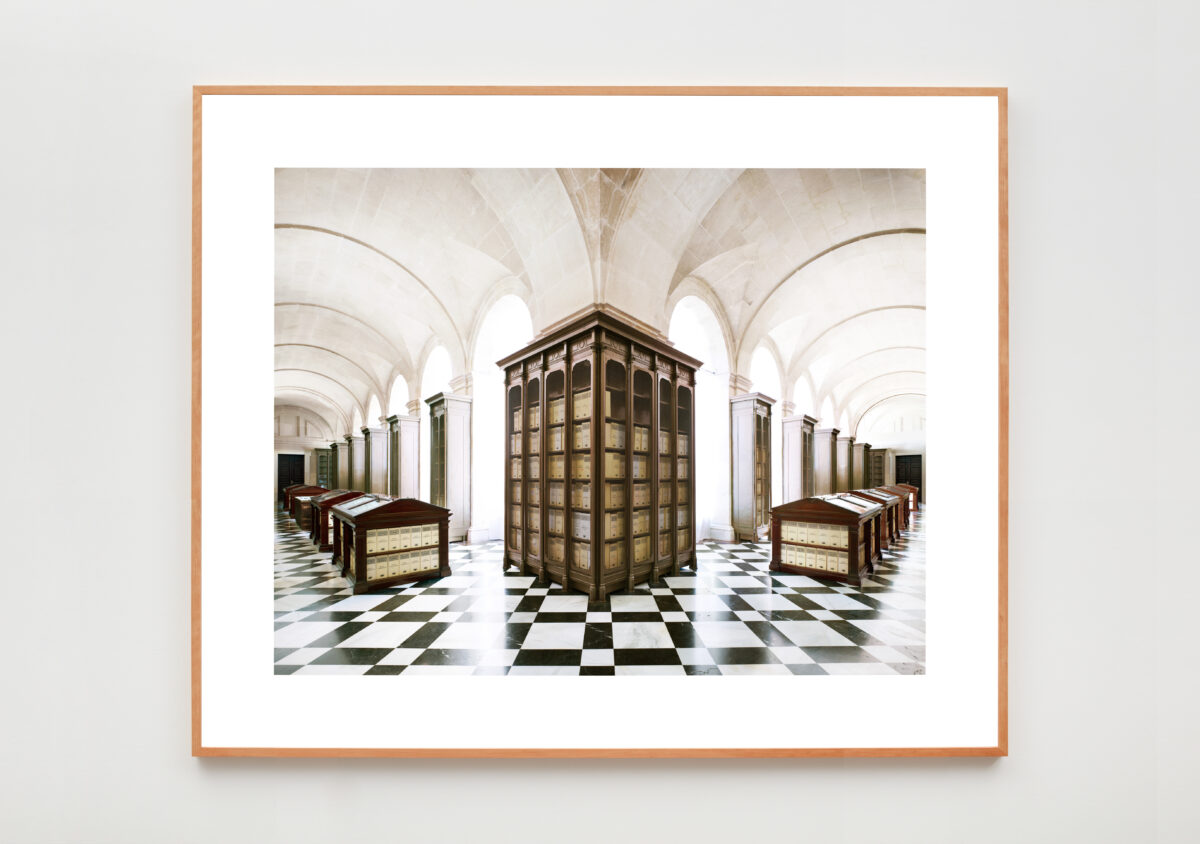

Evron’s work, on view at Andrea Meislin through May 2, focuses on perception and cognition – how do we see and how do we know what we see? At the heart of the exhibition was a sculpture composed of a photographic stand with a cantilevered arm holding a piece of glass on which was printed the picture of a rainbow. It was the reification of an illusion – a phenomenon that is purely optical, translated as a picture to a medium that is physical but transparent and reflective.

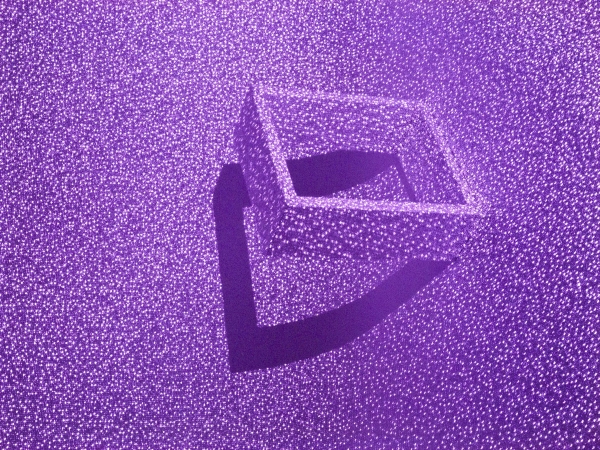

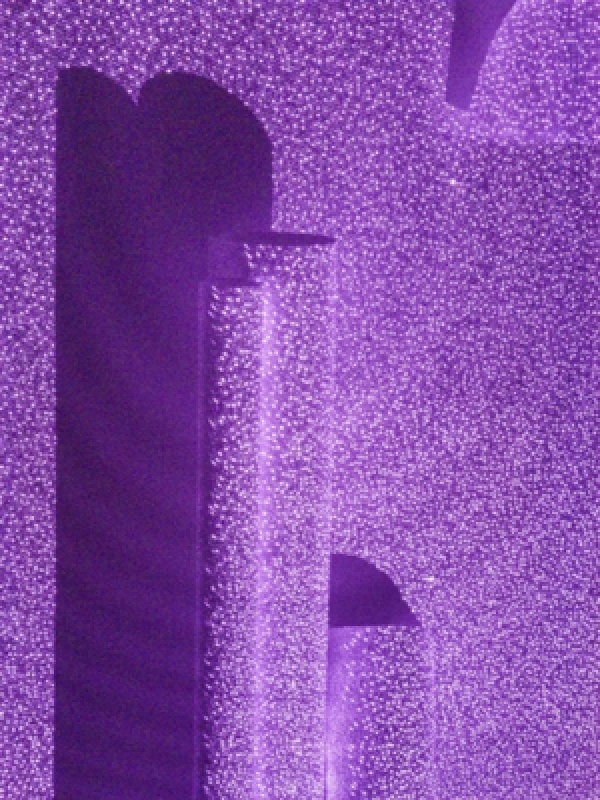

A thing was there but at its center was an illusion, a kind of nothing. The theme was reflected in other works, including wall panels that bore images created by an infrared camera that captured the mapping effects of an X-Box Kinect. In many ways this series, Visual Pyramid (After Alberti), presented the most challenges because it suggested so many things at once: design objects (they were carefully and even elaborately mounted), abstract photographs, virtual noise, pointillist drawing. A handout essay by Abigail Winograd read: “The visual simplicity of Evron’s art belies an intricate working method.” But that was not correct. Nothing was belied. Absent an explanation for each piece, there was no way to engage them substantively, a sure sign that the experience of the work lay elsewhere, in theory and in reflection. As with so many installation works in contemporary art, what you saw was what you saw, but not necessarily what you got – perhaps the perfect summation of our uncertain relation to “the real” in a digital age.