Over the course of three years, while being closed to the public, the San Francisco Museum

of Modern Art has expanded to become double its previous size. It’s touted as the largest gallery space devoted to modern art in the country – and its renowned photography department has expanded in kind.

SFMOMA’s commitment to photography is deeply and historically rooted. From its modest beginnings in the 1930s, the Northern California location, where the f64 group worked, gave the museum an early foothold in the medium. The department has been steadfast in growing its collection and exhibition program, and in its new configuration, as the Pritzker Center for Photography, it has 15,000 square feet of gallery space (double its previous exhibition footage), a study center, new cold storage, and an interpretive gallery with its own coffee bar. With a key location near a new main entrance, the department is given a central position in the museum’s aesthetic ecology.

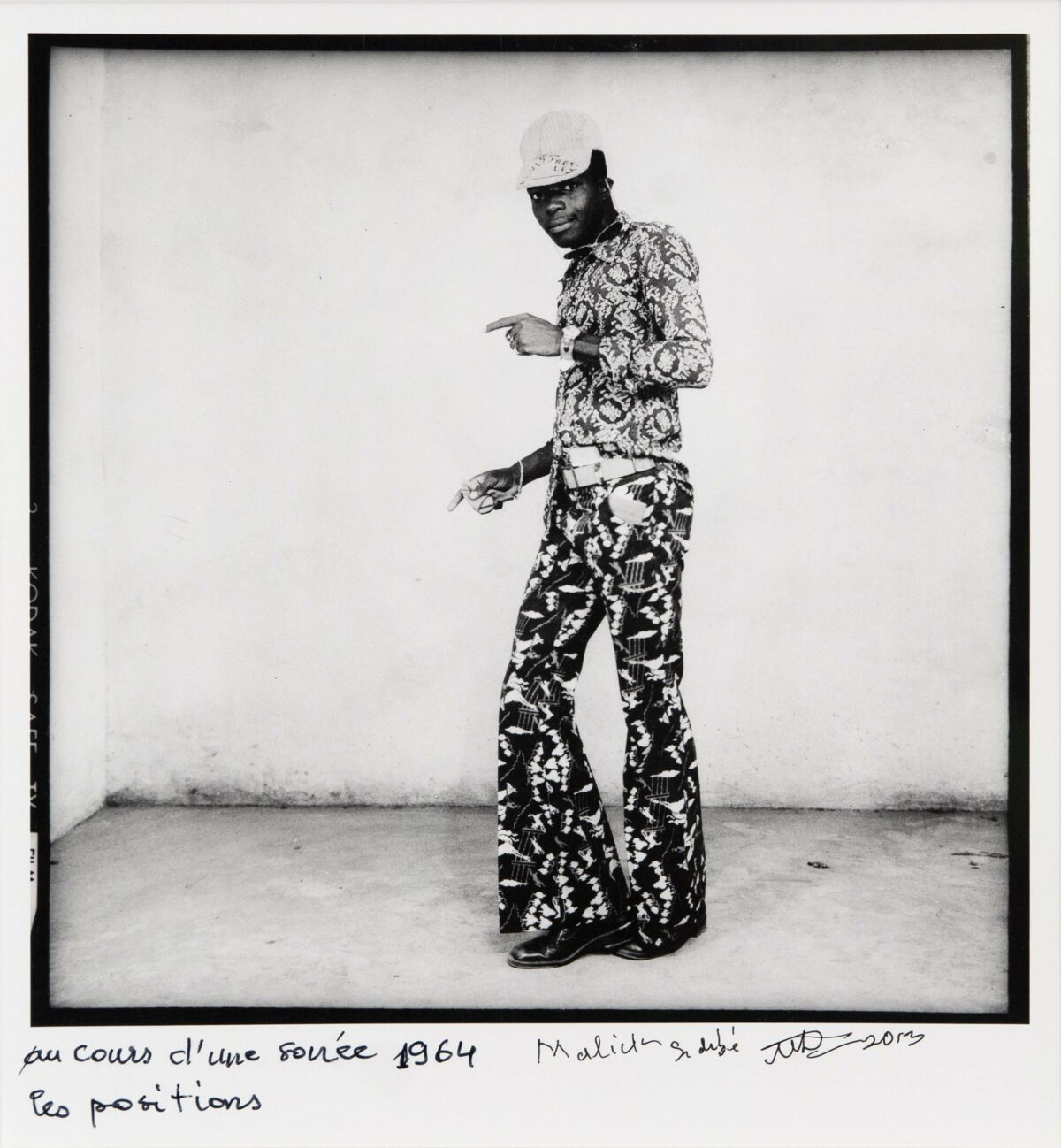

The opening shows are focused on the permanent collection, currently comprising 17,000 works. The inaugural show in the airy special exhibition galleries is California and the West, organized by Senior Curator Sandra Phillips. It is composed of recent and promised gifts and highlights the region’s role in photographic and cultural history. “The American West has been the site of extraordinary development from the time of the Gold Rush, which photography documented, to the realization that some of the land also needed to be saved from development,” says Phillips. “The works reveal the ways in which contemporary photographers either document what is happening or use the medium itself as a new field of exploration.”

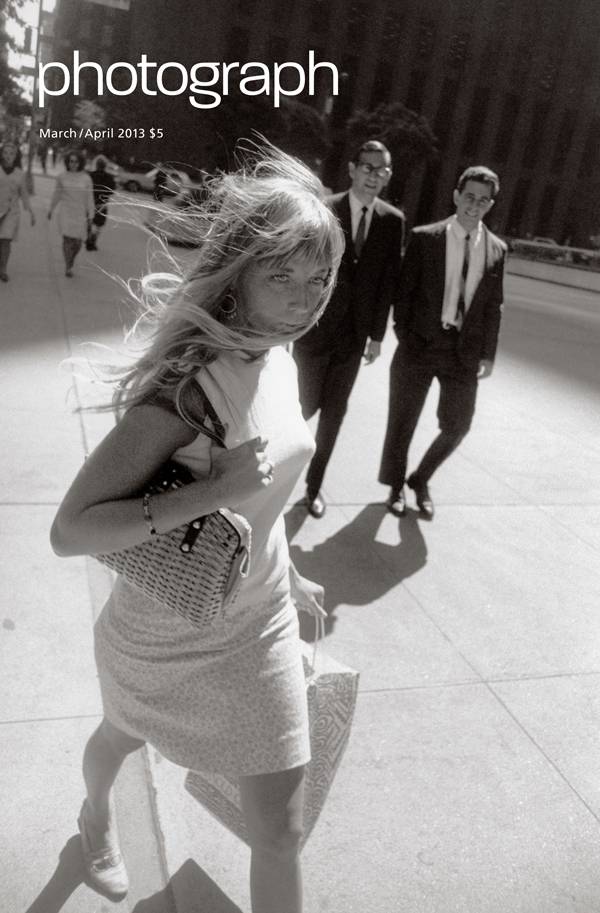

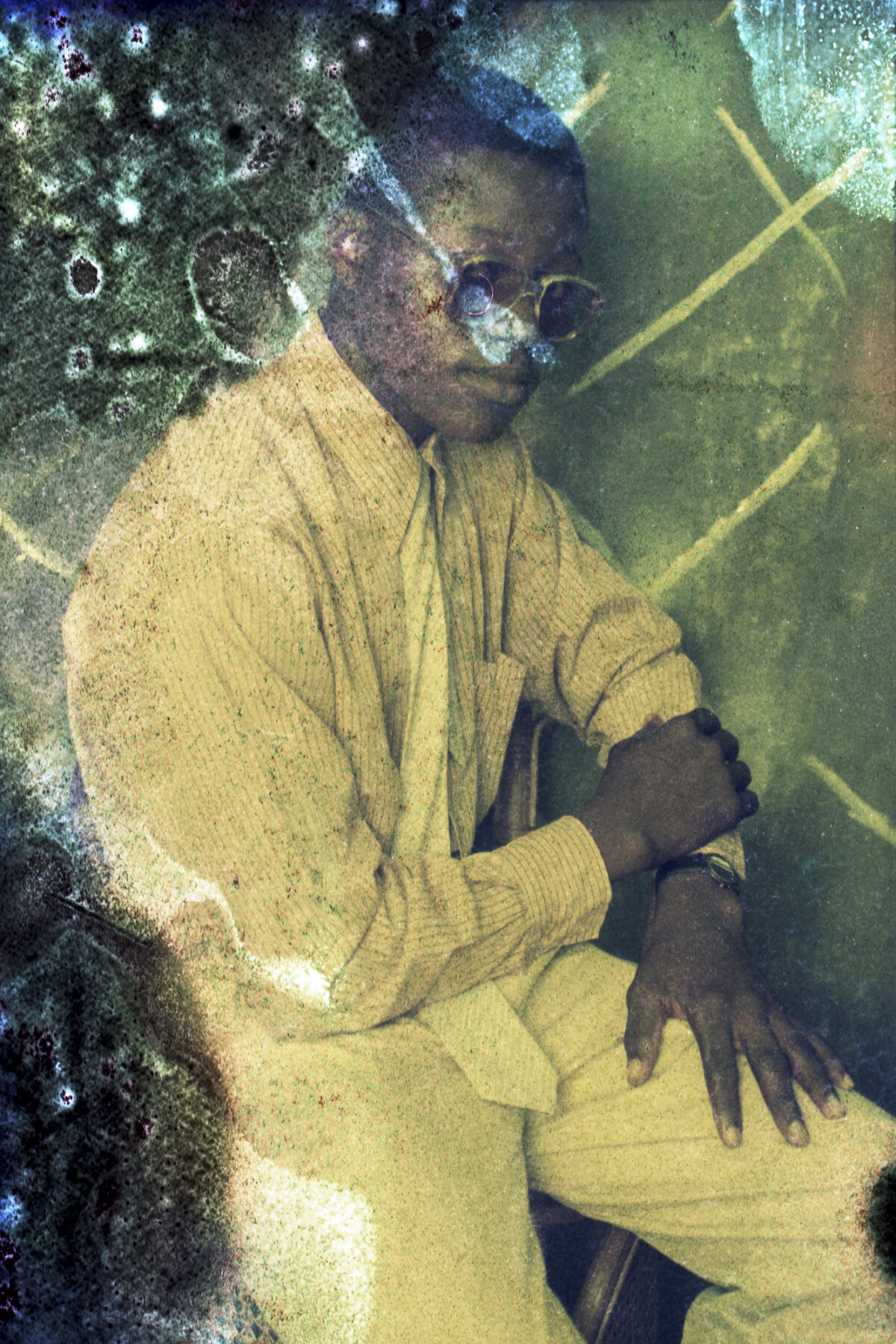

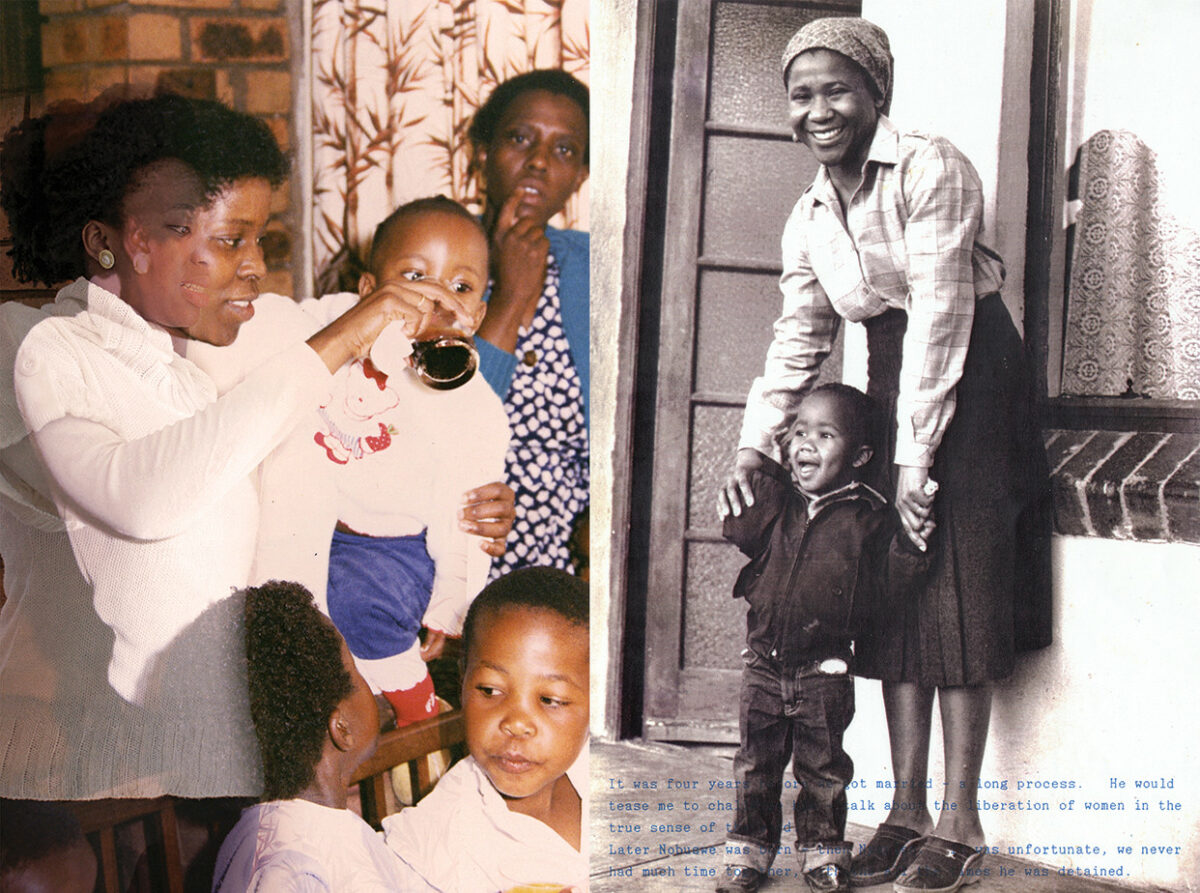

In the modestly reconfigured former photo galleries, About Time: Photography in a Moment of Change, organized by curator of photography Corey Keller, probes topical aspects of the medium. Keller traces the impetus for the show to the advent of Snapchat, the ephemeral photo-sharing platform. “[The app] made me wonder about what photography was today, and what it meant to open a photo floor at this moment in photographic history,” she says. In the course of eight galleries, the show explores themes of temporality with a mixture of historical and contemporary works – Eadweard Muybridge faces a work by Paul Graham in a thematic gallery – a strategy that the department has long employed.

That idea also seems to spill into the interpretive gallery, which occupies a space that traverses the old and new wings, making it a place to linger and learn more about the medium via interactive exhibits and museum-produced films on artists. “These provide viewers with a set of tools to talk about any photograph,” says Keller.

The opening of the Pritzker also is a turning point in other ways. Phillips, who has headed the department since 1987 and brought thousands of works into the collection, will retire soon after the museum’s May re-opening, though she’ll retain emerita status and continue to work with the institution. Whoever replaces Phillips will not only inherit the formidable foundation she has built, but also a state-of-the-art facility primed to adapt to photography’s ever-evolving future.