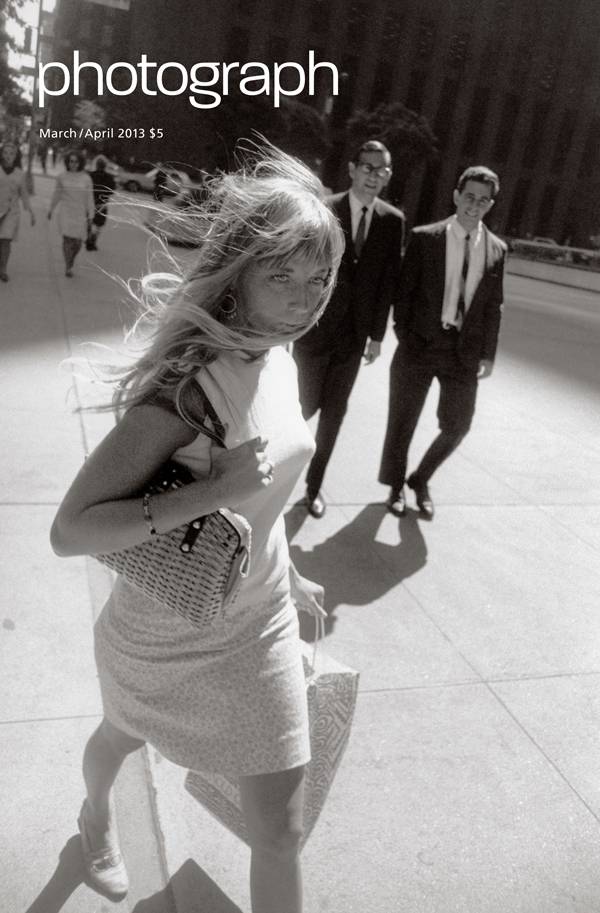

For Garry Winogrand, where the sidewalk ended, infinity began. The Winogrand we know by reputation, the prowler with a camera who changed the nature of street photography from political tendentiousness to risky improvisation, is based on a comparative handful of the many thousands of pictures he made. They are typified by the image on the cover,New York, from 1965. It’s a product of serendipity and determined pursuit on the streets of Manhattan. Winogrand, often accompanied by photographer friends such as Joel Meyerowitz and Tod Papageorge, would stake out territory in midtown and track situations as they unfolded, waiting for a picture to come together – for the woman in the summer dress to come in range and the camera to collect her and the two suited men in its frame. His best pictures walk a line between chaos and immanence, chance and structure. But such pictures don’t tell anything like the whole story. When Winogrand died in 1984, he left behind a mountain of some 300,000 unpublished – and mostly unseen – images, on thousands of rolls of unprocessed film, not to mention thousands of unedited contact sheets. Only a comparative handful of these works have ever been published or even printed. The San Francisco Museum of Modern Art is rectifying that enormous gap with what must be seen as the first true Winogrand retrospective (March 9-June 2), a presentation of more than 300 images organized by the photographer Leo Rubinfien (a friend of Winogrand’s), SFMOMA assistant curator Erin O’Toole, and Sarah Greenough, curator from the National Gallery of Art. Many of the images are profoundly unsettling, as only a photograph by Winogrand, the perpetual voyeur, can be. Yet they seem to court chaos and flaunt technical rules more flagrantly than anything the photographer ever published. That’s partly because Winogrand himself changed, shooting ever more compulsively, so that by the end of his life he barely looked where the camera was pointing. Giving up the sidewalk after he moved West in the 1970s, he shot frequently from the front seat of his car. And as Rubinfien points out, “The ratio of good pictures to bad or casual ones inevitably went down.” This explains why John Szarkowski, who championed Winogrand early on, dismissed most of the late work. But it also raises the question of whose Winogrand we actually see at SFMOMA. The curators who sifted the vast archive chose the unseen works from unedited contact sheets and directed the printing, all without input from the artist. Over the decades since his death, a number of critics have insisted that such a liberty never be taken. Yet the Winogrand who emerges at SFMOMA is the artist we know, only more extreme. In the curators’ selection, the true and impossible nature of his quest stands starkly revealed: to gather every possible image a camera might witness and thereby confirm the reality of the world.

Categories