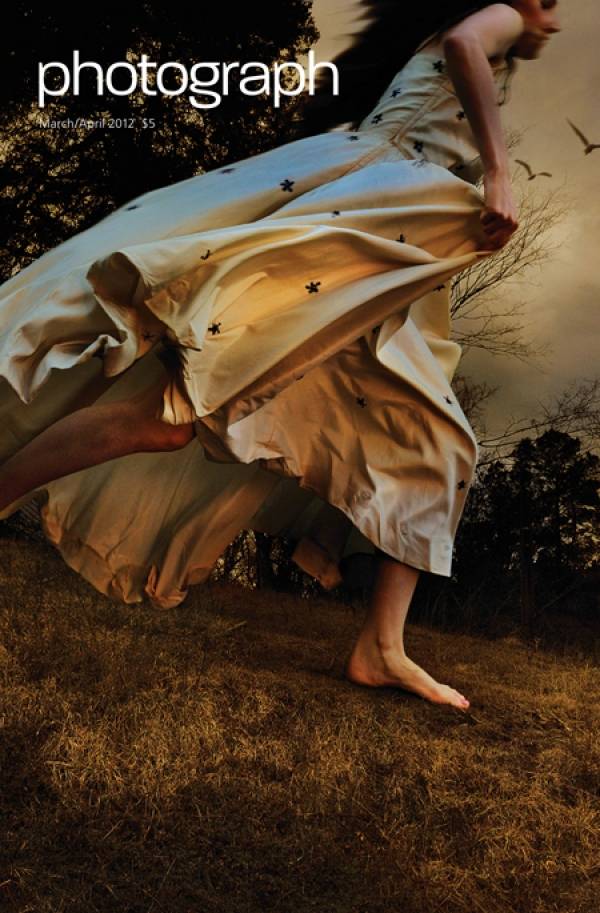

In an ongoing project, photographer John Cyr is creating an elegy for the darkroom, a series of images of dented developing trays of famous photographers. All but gone now are the toxic fumes and the alchemical formulae, cramped, red-lit basement chambers, caches of paper in the refrigerator and elaborate notebooks of mistakes and successes. “Photoshop is the new darkroom, and layering and filters have replaced dodging and burning,” says Mark Pinsukanjana, co-owner with Bryan Yedinak of Modernbook Gallery in San Francisco. A primary case in point is the work of Tom Chambers, who has 29 prints on view at the gallery through June 2. The gallery has also published a new book of his work, Entropic Kingdom. Chambers has made the darkroom into a lightroom through digital software. And he has eliminated the kitchen table—that place where Hannah Hoch put together her collages by cutting and pasting with a knife and a little glue. Chambers uses the computer as a device to liberate camera images from their contexts and redeploy them in tableaus and stories of spiritual, political and environmental import. The cover image, Winged Migration, 2009, is made of photographs Chambers took and then digitally stitched together. It seems to gesture toward documentary reality, toward an unfolding event of environmental disruption, the confrontation of birds and people or their collective flight in the face of…what? Yet it more strongly evokes Alfred Hitchcock’s film The Birds and the landscapes and figures of painter Andrew Wyeth. Likewise for Chambers, Mexican ex-votos, the early Renaissance frescoes of Taddeo Gaddi and Giotto, and the psychological landscape of dreams have all served as models and inspiration. Pinsukanjana refers to surrealism in discussing Chambers’s work, but the precedent for his digital staging of symbolist tableaus occurs much earlier, in the Victorian set pieces of Julia Margaret Cameron and Lewis Carroll, among others. Their models were the words of poets like Tennyson and the images of painters such as Burne-Jones, and their exploitation of photography’s mute witness before its subjects elevated the status of legend and metaphor to that of fact. The broad adoption of a more realistic or “objective” approach to photography after World War I

banished such fantasies, but Chambers’s work reveals above all that our expectations for photography are shifting. Photographs themselves are artifacts, not evidence; their umbilical relation to an antecedent reality can never be assumed. One picture of one instant in one world seems an intolerable prohibition when we ourselves live in many worlds simultaneously, all of them symbolically intricate. In Chambers’s digital chamber, many pictures/moments/worlds are convened to make one image in a time of no time, and the camera, once a guarantor of “truth,” is now the signal of a conviction: that what we experience can be seen and what we imagine can be shown.

Categories