“Critical Geography” is the big, loose theme of this year’s FotoFest Biennial. Like the arterial highways of Houston, the exhibition’s longtime home, this curatorial idea is a nexus of both convergence and dissipation. It drives the show’s flow, but more interesting are all the detours along the way.

This is the 20th edition of FotoFest since it was founded by documentary photographers Frederick Baldwin and Wendy Watriss, along with gallery director Petra Benteler, in 1983. It was branded as the first photography biennial in the country, and its age distinguishes it from the many regional bi- and triennials that have popped up in recent decades – but its artistic identity is hard to put a finger on, too. While recent iterations have honed in on lens-based artists of specific regions around the globe – Russia in 2012, India in 2018, diasporic Africa in 2020 – this year’s edition widens its ambit. Named after the academic field of the same name, a progressive branch of geography calibrated toward social justice, the 2024 show purports to reexamine “traditional Western and historical understandings of geography” and explore “how space, place, and communities are influenced by social, economic, ecological, and political forces.”

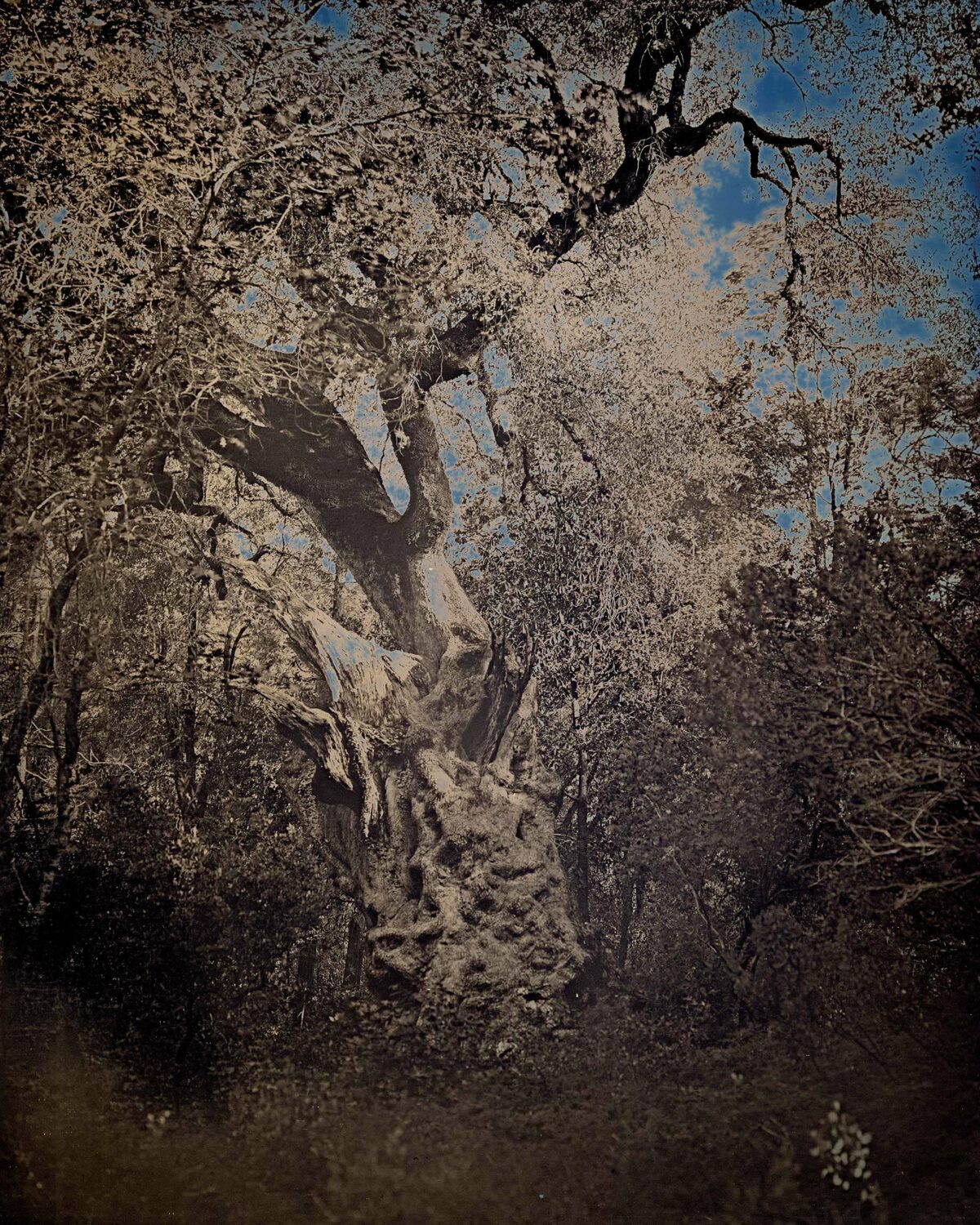

The broad language of this prompt leaves myriad lanes for the exhibition’s 24 participating artists to settle in. With his Exile to the Red Planet project, Hong Kong photographer Caleb Fung documents the ways in which the region’s ancient Banyan trees have fused with municipal architecture – a symbol of resilience framed against mainland China’s ongoing efforts to reshape the city-state. C. Rose Smith’s series of self-portraits, Talking Back to Power, features the Memphis-born artist posing defiantly on the sites of southern plantations turned into tourist attractions. And through her Block Out the Sun body of work, the California-born artist Stephanie Syjuco rephotographs old, staged pictures of “natives” in an artificial Filipino village that was fabricated for the infamous 1904 World’s Fair in St. Louis.

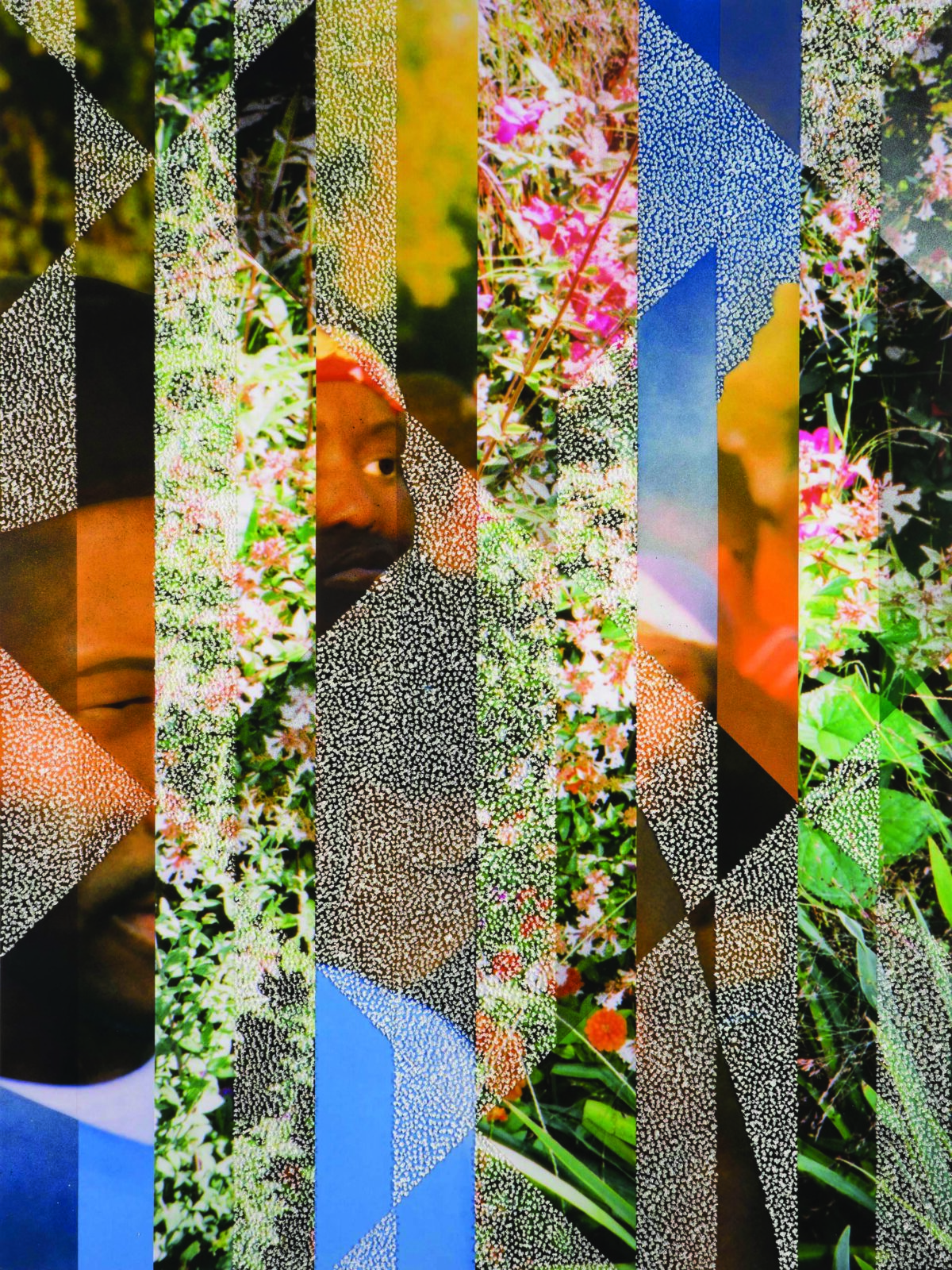

Like Syjuco, several exhibition participants manipulate archival or documentary material to redress the historical erasure of the disenfranchised peoples depicted therein. There’s a fine line between drawing attention to injustice and simply recapitulating it, though, and not every artist ends up on the right side. For his Forgotten Struggle series, Houston-based image maker Phillip Pyle II digitally removes the words from picket signs in photographs of 1960s-era Civil Rights marches, leaving a checkerboard of blank white rectangles floating above the crowds. The idea, according to the wall text, is to reflect the “omission of Black revolutionary actions from in-class curricula in Texas schools,” but Pyle’s alterations do the opposite, effacing the marcher’s messages – and undercutting the real, tangible impact of their movement.

Artist Siu Wai Hang attempts a similar maneuver in his Clean Hong Kong Action series, based on photographs he took during the wave of anti-extradition protests that rocked the region in 2019-20. Photography was widely opposed by participating demonstrators, who feared that the resultant images might later be used to identify and punish them, and Hang honors their efforts by punching holes over every participating protestor’s face. By physically removing the subjects of these protests, the artist risks making the same mistake that Pyle did. But in shots of larger crowds, the holes overlap and form huge, scalloped patches of negative space that add up to something else: a stirring portrait of people who have given their identity over to a cause. Their anonymity is their power.

There is a kind of violence to the way Pyle and Hang altered their subjects, and that’s true of Binh Danh’s biennial contribution, too, but in his work, the audience is made party to the crime. For his new all I asking for is my body series, the Vietnam-born, Bay Area-based artist printed daguerreotypes of Jim Crow-era plantation laborers atop old silver plates. Coupling these exploited workers with status objects they could never afford feels, at first, like a cruel twist of the knife, but catch a glimpse of your face in their polished reflections and you’ll see what Danh is really after: a layered portrait of complicity.

Many of the most successful artworks in Critical Geography access lofty geopolitical issues through the lens of the local, though few do so via Houston or the wider American South. The imbalance is curious, if only because the region makes for such a rich text. Consider, for instance, its historical ties to slavery, oil, and domestic trade, or its current status as a sprawling urban mecca, a gateway to the Gulf, a launchpad to the stars. To some extent, the exhibition loses sight of its own positioning en route to more ambitious global aims.

Then again, the biennial constitutes more than the art on the walls of its central exhibition. Also under the FotoFest umbrella is a film program; a series of workshops, talks, and book-signings at dozens of partnering businesses; and the long-running 10×10 portfolio review, which brings in 150 curators and editors to review the work of some 450 photographers from around the world. If Critical Geography is the highway, then these programs are the byroads – and it’s largely through them that FotoFest honors the hub that is Houston.