Identity and uneasy notions of place inform After the Gold Rush, on view through November 2. Binh Danh is widely lauded for perfecting chlorophyll prints in series such as Immortality: Remnants of the Vietnam and American War, 2000-08. The artist superimposes a photographic negative onto the surface of a leaf, and then exposes it to sunlight for a day or so. Through photosynthesis, the image is imprinted into the plant fiber, which the artist then seals with resin. The objects mirror the curiosity and reverence for life captured in Anna Atkins’s cyanotypes, but also the brutality of war visited upon Vietnam, Danh’s birthplace, which his family fled in 1977.

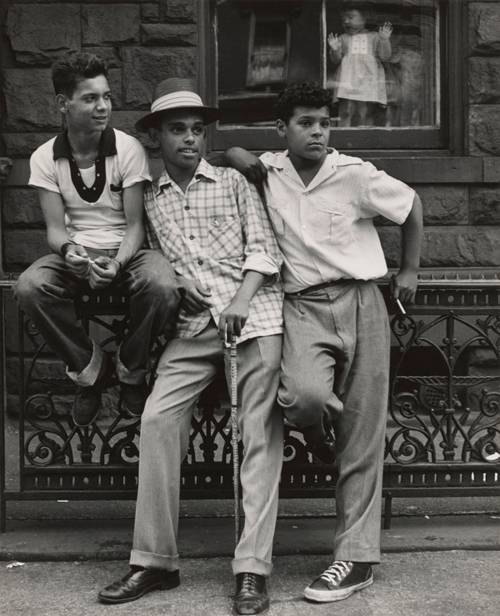

After the Gold Rush builds on Danh’s work with daguerreotypes, which began with the 2012 series Yosemite. In a 2012 interview with art historian Boreth Ly published by Haines Gallery, Danh notes that photographing the beloved national park helped him negotiate otherness and the place of an Asian body in the natural and constructed American landscape. That inquiry deepened over the course of Danh’s 2019 artist residency in Nevada City, once California’s most prosperous gold-rush town and now a sleepy and well-heeled mountain community.

Danh commits his creative capacities to understanding his adopted country through the often unheralded narratives that shape it. In Cannabis Farm, a farmer quietly tends to rows of California’s latest cash crop. The image recalls photographs of farmers at work in lush fields across the American Midwest and rice paddies throughout Asia, laborers separated by vast geographic and cultural distances but alike in their desire to draw life and livelihood from the land. It is a visual nod to Danh’s origins, his adopted home, and the millions of immigrants who helped build California and the United States, but whose contributions go largely unacknowledged in the nation’s origin story.

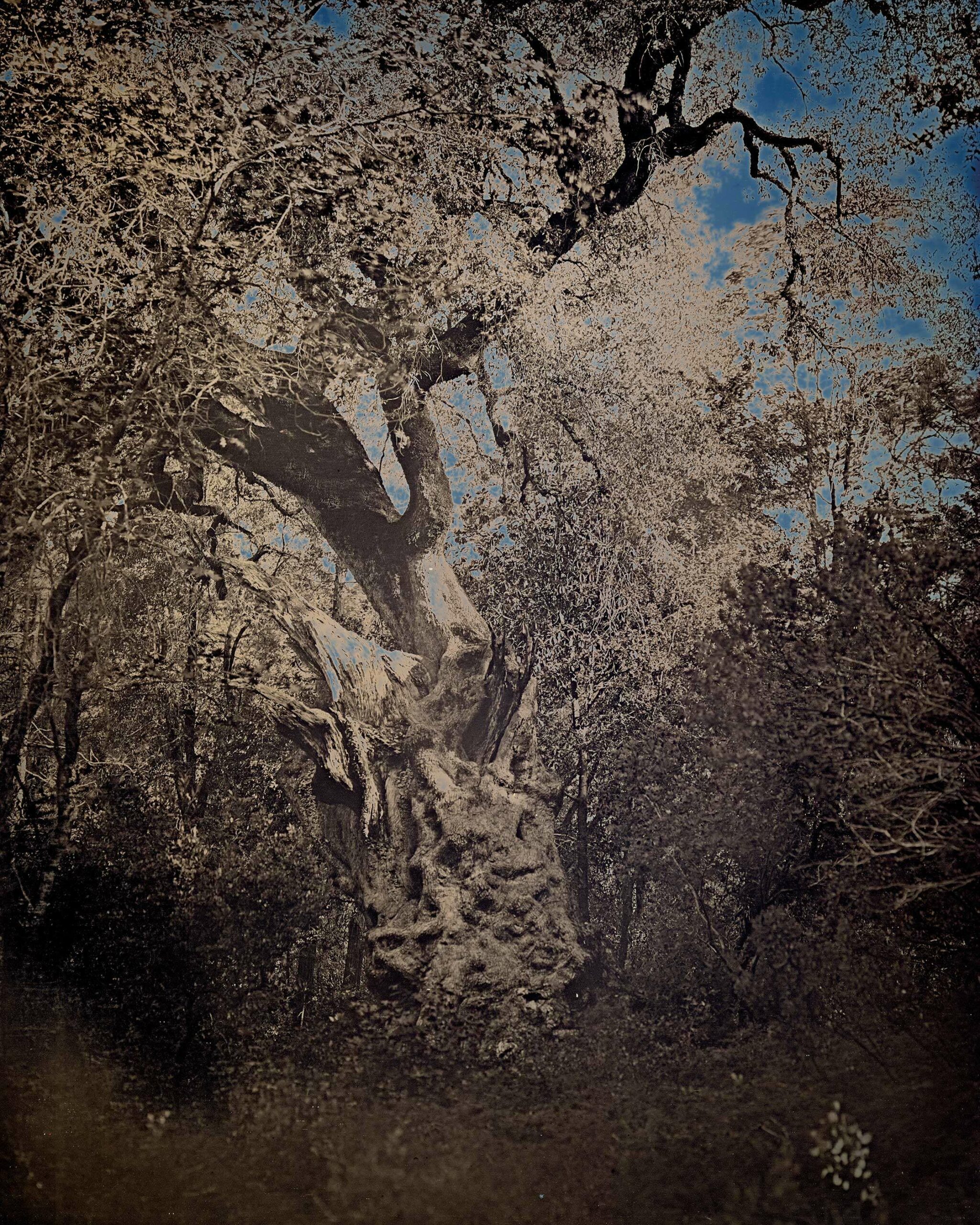

In addition to views of historic commercial facades such as National Hotel on Broad Street and Nevada City Chamber of Commerce, which convey the rustic appeal of small-town California, Danh presents images – Heritage Oak and View of the South Yuba River Gorge – that suggest what the land might have looked like before 1849, when Nisenan Native Americans inhabited the region. Defying the arresting visual clarity that make daguerreotypes unique, Heritage Oaks conveys the gnarled trunk and thick surrounding brush as impenetrable, willfully resisting easy photographic interpretation.

Under the best conditions, daguerreotypes are notoriously difficult to exhibit because the silver-plate polished surfaces reflect whoever stands before them. When viewing Binh Danh’s work, however, this is an added benefit. Viewers cannot help but see themselves as a part of the composition, and by extension, as actors in a perennially contested national narrative about the land we inhabit, who may lay claim to it, and who is welcome here.