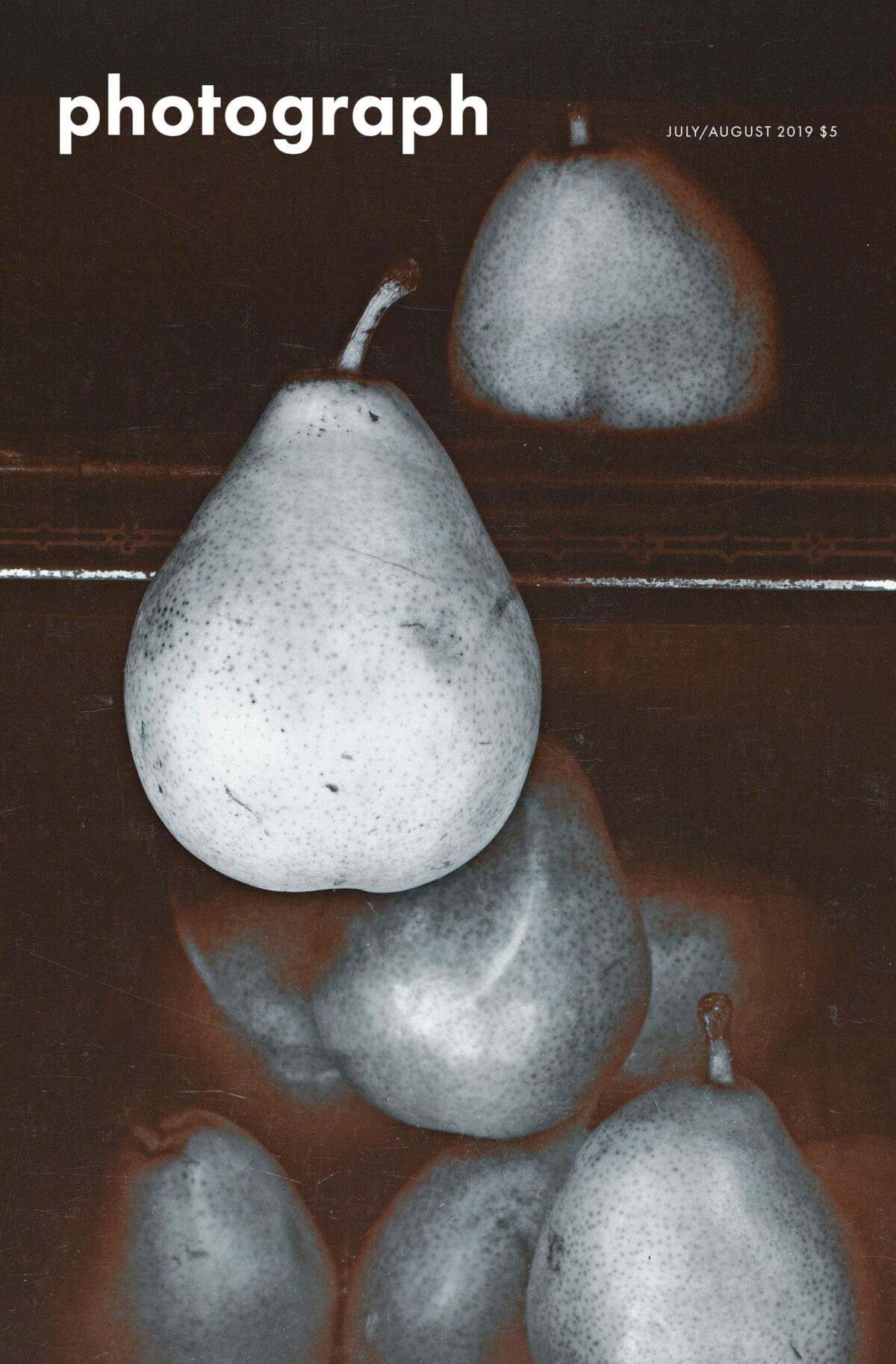

Much theorizing has been devoted to the origins of photography and its precursors in various artistic traditions. Still-life painting of the 17th century has to be a candidate. Even more than the portrait, the still life placed the heaviest emphasis on a superficial realism, that is, a realism of appearances and the techniques of illusionism to support it. Perhaps that is why it was considered the lowest of the painting genres. But there is a deeper underpinning. In order for the painter to make a moral point about the vanity of desire or the transience of earthly things, often the primary goal of a still life, fidelity to the perceived textures of the world’s objects was crucial. In order to teach, you must first convince, a lesson understood by artists from Caravaggio to Chardin. And by photographers.

Photography’s one great virtue was its convincingness, a fidelity to appearances, and it is this attention to surface and appearance that Tara Sellios exploits to tell other kinds of stories in her photographic still lifes. The cover image, Untitled No. 8, from the series Luxuriaon view at Gallery Kayafas from May 22 to June 27, partakes of both allegorical and Surrealist traditions, vanitas and bad dreams. A plucked goose stuffed with grapes and lilies hangs from a cord, its head plunged into a glass of wine. On the one hand, it’s an intensely immediate and contradictory image, prompting a collision of sensations all stimulated by the eye. In an earlier series, Sellios staged octopi in silver bowls. André Breton would have loved the violence and surprise. On the other hand, it seems to offer a lecture as stern as that of a Bible belt preacher about the consequences of indulgence: luxuria in the Latin is excess, one of the seven deadly sins. The bird is overstuffed and drowning in what has become a symbol for lifestyle as a consumable commodity – wine. Wine is everywhere in Sellios’s images, spilled in profusion on tablecloths and walls, covering animal carcasses and staining flowers.

“She seeks to represent the totality of human existence,” says Arlette Kayafas, “the feel and even the smell of it. We are invited to enjoy the lasciviousness of wine, the consumption of food, because life is passing.” Invited and repelled. For the delirious consumption of food takes place against a backdrop of national inequality and global privation that mocks enjoyment. Just so, in the 1600s, paintings of overflowing larders and tables both disguised and alluded to the harsh game laws that made peasants’ desperate subsistence hunting subject to charges of poaching, with harsh penalties. And if the tulip once was a symbol of economic cupidity, the lily is equally dense symbolically, with a range of associations from modesty to gaiety to restored purity after death. The ultimate irony of Sellios’s still lifes is that they indict the viewer through the very means of their moral address – the seduction of seeing.