This exhibition, the first retrospective dedicated to South African photographer Zanele Muholi in France, opens with the series Being, from 2006, images of same-sex couples in the privacy of their homes, photographs characterized by tenderness and intimacy. Muholi’s unabashed images show aspects of the body that are usually kept out of sight: menstruation, nudity, pores, hair, stretch marks, and scars. They also allude to tough subjects, such as identity crises, hate crimes, and corrective rape: a gentle close-up of a young person’s wrists encircled in plastic hospital bracelets, titled Hate Crime Survivor (2004), for example, or a photograph of a young woman carefully binding her breasts.

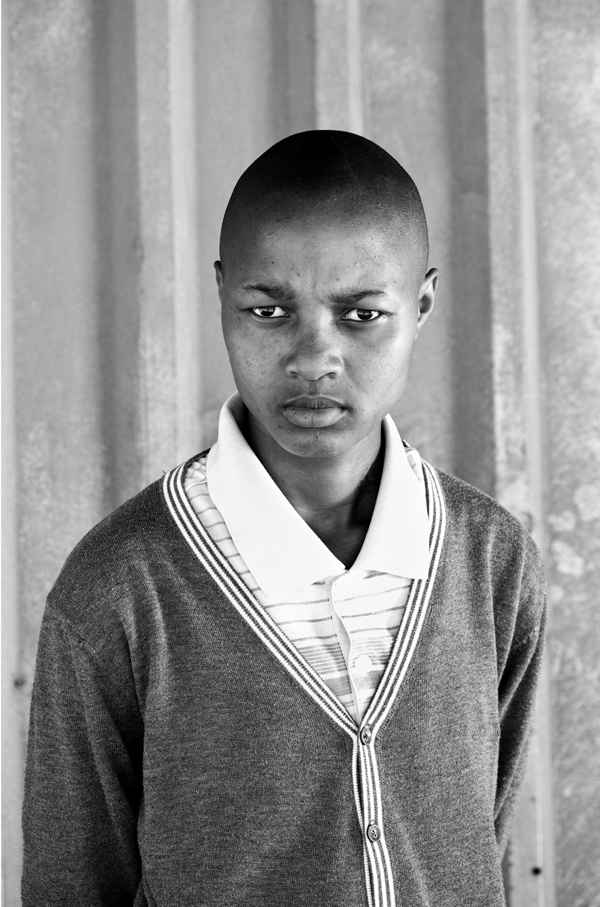

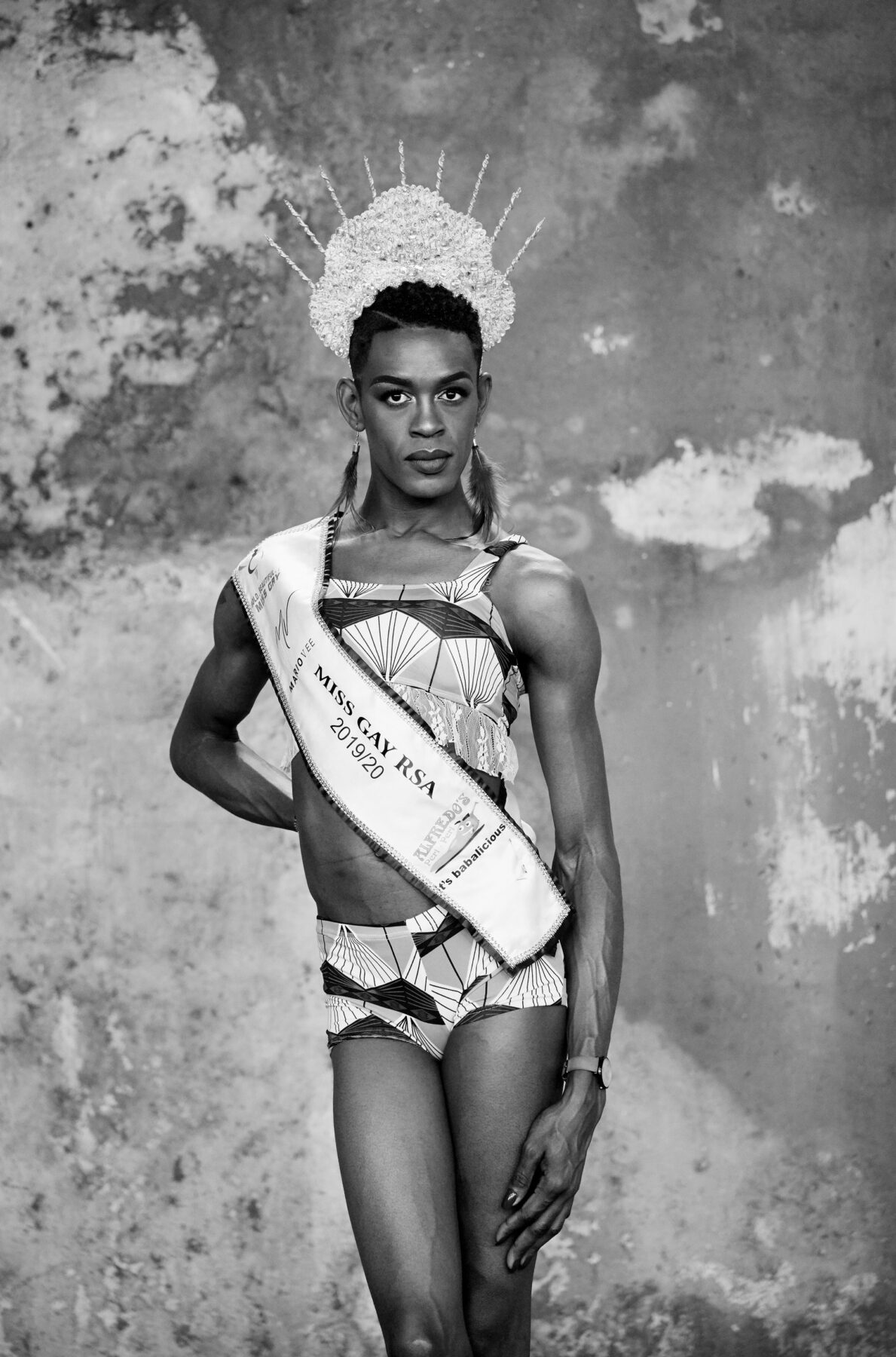

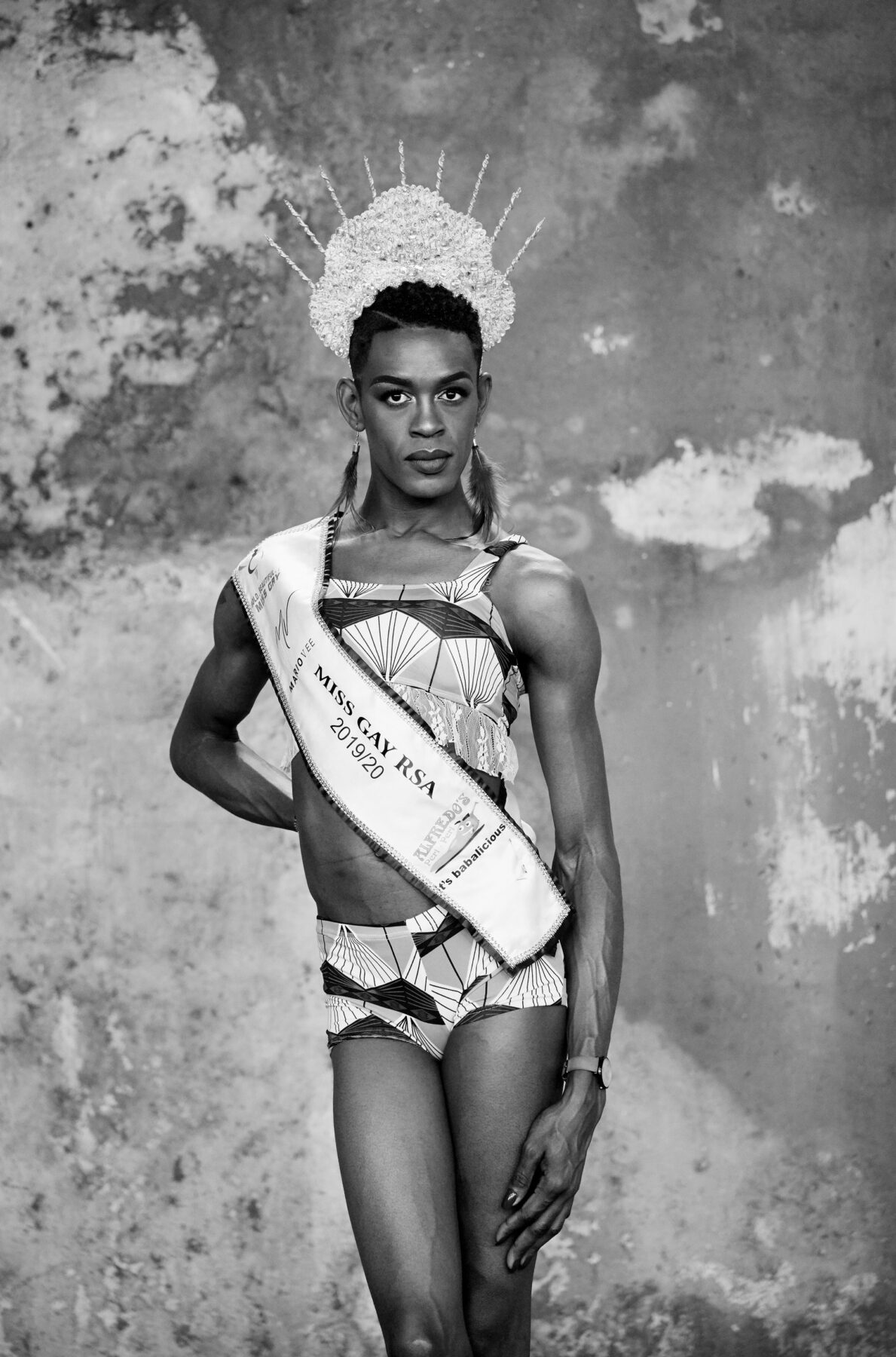

As an advocate for LGBTQIA+ rights and for the Black community at large, Muholi, who calls themselves a visual activist, uses their camera as a weapon in the fight against injustice, and the colorful, luminous images in the second gallery trade the gentleness of intimacy for the fervor of activism. The series Brave Beauties includes celebratory portraits of drag queens and transgender and non-binary women. Muholi aims to give a queer dimension to public space, and that ambition also drives the project Faces and Phases. Since 2006, they have documented members of the LGBTQIA+ community in South Africa. A true living archive, the series now comprises over 500 portraits, a selection of which cover the walls of this exhibition. The photographs are uniform in size and composition, and the subjects, who gaze straight at the camera, are all photographed in black and white, using natural light.

In the series Somnyama Ngonyama, Muholi turns the camera toward themselves to challenge the image of the Black woman through history. The title, meaning “Hail black lioness” in Zulu, represent a resistance to Eurocentric standards of beauty (see the array of silver hair picks in Qiniso, The Sails, Durban). The everyday accessories they use to adorn themselves suggest other readings as well: in Fisani, Parktown, the safety pins might be read as a symbol of efforts to hold their community together. A crown of scouring pads (Ntozakhe II, Parktown) or clothespins (Bester I, Mayotte) recalls Muholi’s mother, Bester, a domestic worker who spent 40 years working in a white household.

The final part of the exhibition, on view through May 21, includes photographs of weddings and funerals, testimonies to the rituals of everyday daily life, as well as photographs of demonstrations and marches, including the 2014 Johannesburg Pride March, the 2018 Total Shutdown March in Pretoria, or the 2019 #AmINext march in Cape Town. After the self-portraits in Somnyama Ngonyama, the images in the final gallery focus outward, on the wider community to which Muholi belongs and for which they advocate.