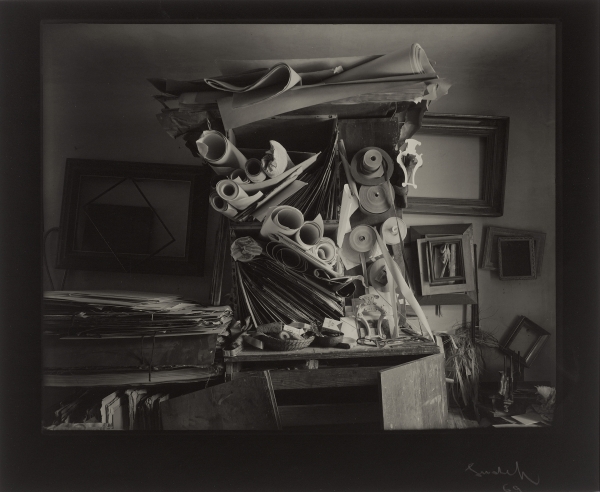

West Coast photographer Wynn Bullock was a modernist whose work incorporated technical innovation and scientific discovery, influences that are as apparent in his work as his regard for raw nature. A retrospective on view at the High Museum of Art through January 18, 2015, provides an excellent overview of his work and serves as a mini-history of modernist photography, ranging from straight photography to experiments with light and color. Curated by the High’s Brett Abbott in collaboration with the Center for Creative Photography in Tucson, the show features 108 prints, 43 of which are part of a recent gift to the High of over 100 photos from the artist’s estate.

Bullock originally pursued a career as a singer and while spending time in Paris in the late 1920s, he first saw the work of avant-garde photographers Moholy-Nagy and Man Ray, which set him on his own path of photographic inquiry. His creative experimentation neatly dovetailed with his interest in science.

In attempts to express his ideas about such themes as man’s relationship to nature and the passing of time, Bullock often staged scenes that juxtaposed opposing qualities, as in the photograph of his young daughter lying naked beneath towering, centuries-old redwoods (Child in Forest, 1951), or the smooth skin of a woman, her back to the camera, a small, vulnerable presence amid the craggy and majestic trees (Nude Torso in Forest, 1958).

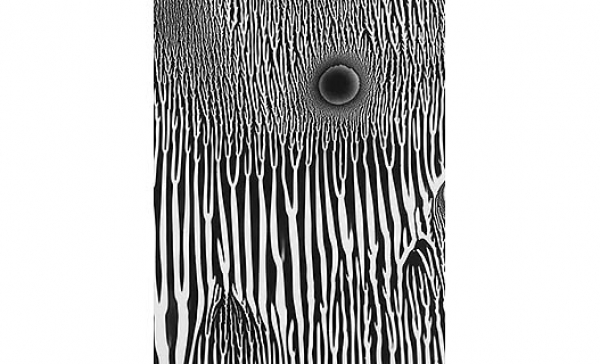

Bullock achieved an effect that, for him, illustrated the time-space continuum by experimenting with longer exposures. In The Pilings (1958), for example, water flowing around the structural remnants become a blur, and the pilings, seen in such an ethereal setting, take on the appearance of ancient ruins. Similarly, Bullock masterfully captured the micro/macro dichotomy in Sea Palms (1968); what appears to be craggy mountaintops studded with swaying palm trees and enshrouded in fog is, in fact, algae growing on tidal rocks continuously lapped by water.

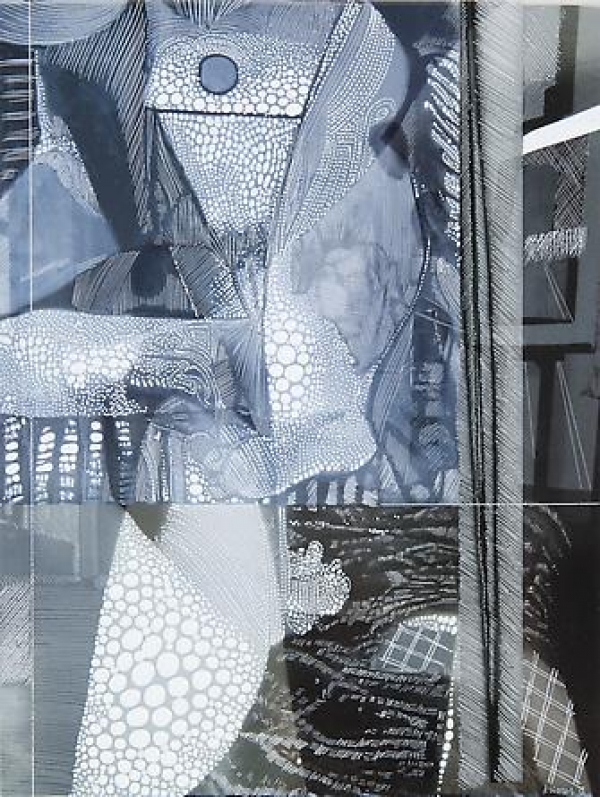

Bullock is especially effective in evocative, abstract works. A group of photos of rocks and trees in which Bullock discerned human faces effectively alludes to our intertwinement with the natural world. Similarly, an untitled 1972 work shows a woman on a beach, partially embedded in the washed-over sand, her bent legs echoing the craggy rocks behind her.

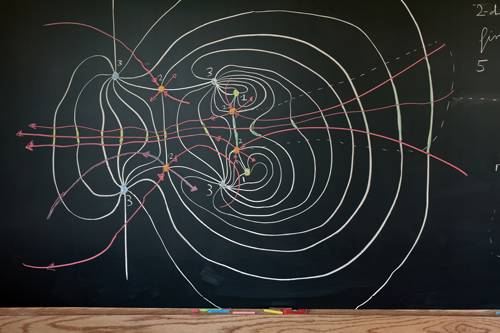

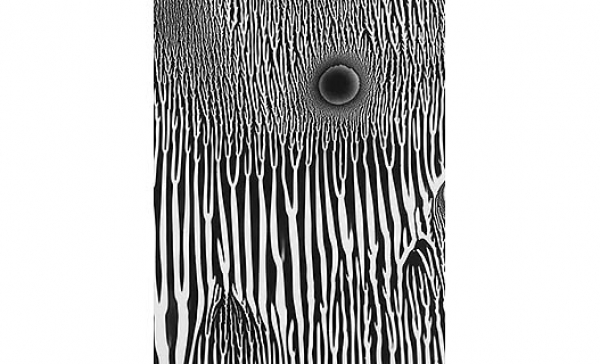

Possessing a photographer’s fascination with light, Bullock experimented with such techniques as solarization and photograms beginning in the late 1930s. For his Light Abstraction series of the ’30s and ’40s, he projected beams of light in his studio and photographed the patterns. In the ’60s, he shone light through thick glass and shot the refracted colors, creating, in essence, images of pure light. The colorful abstractions, anomalies in his oeuvre, resemble Hubble telescope images of the cosmos that would come decades later. They perhaps best achieve his stated desire, to “make what is invisible to the eye, visible.”