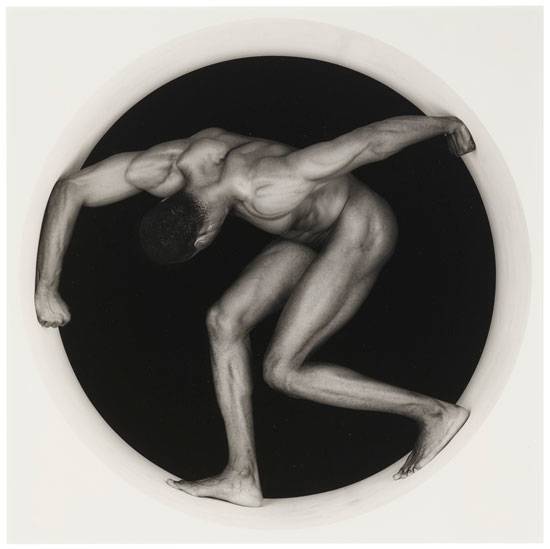

Before he was President of the United States, the Illinois senator Barack Obama selected a suite of photographs by Paul D’Amato to hang in his congressional office. The images depicted scenes from the lives of regular people—a child, an old pastor—in Chicago, Obama’s hometown. D’Amato is known for his editorial approach to portraiture—he has shot for the New York Times, Adbusters, and Life magazine. His sensitive attention to the sitter’s emotional and social realities, and his focus on subaltern subjects, makes his images well suited to an institutional context, especially one with a social mission. Who wouldn’t want to be on the right side of an image campaign that dignifies the lives of poor, segregated, and struggling people?

On view through November 24 at the DePaul Art Museum, We Shall is a survey of photographs, from 2004 to 2013, culled from D’Amato’s weekly excursions into Chicago’s West Side, a notoriously poor, violent, and segregated region of the city. When one of Chicago’s last inner-city public housing developments was evacuated and demolished this past decade, D’Amato was on the scene to document the residues of life from a population forced on yet another diaspora. Most of the Cabrini-Green residents relocated to the West Side.

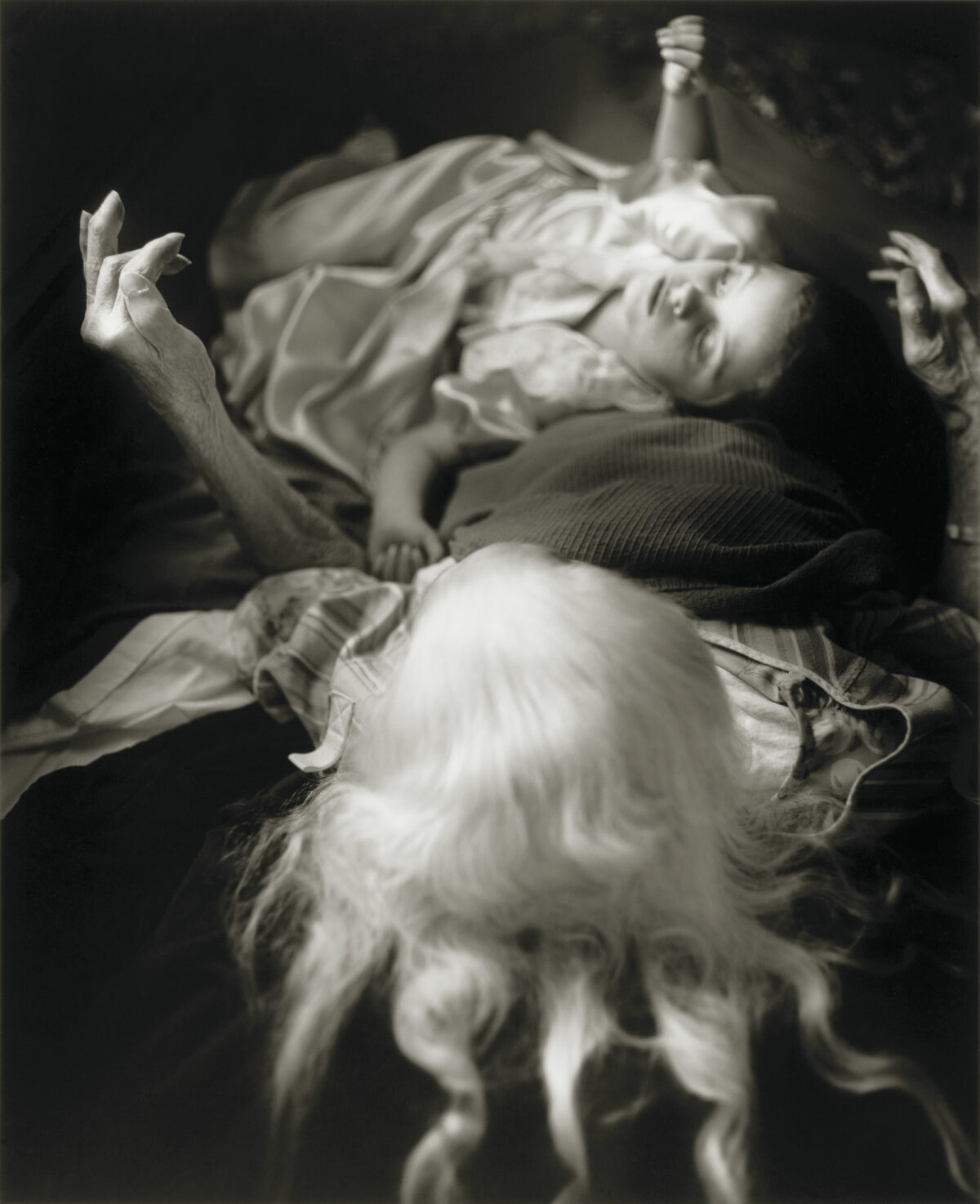

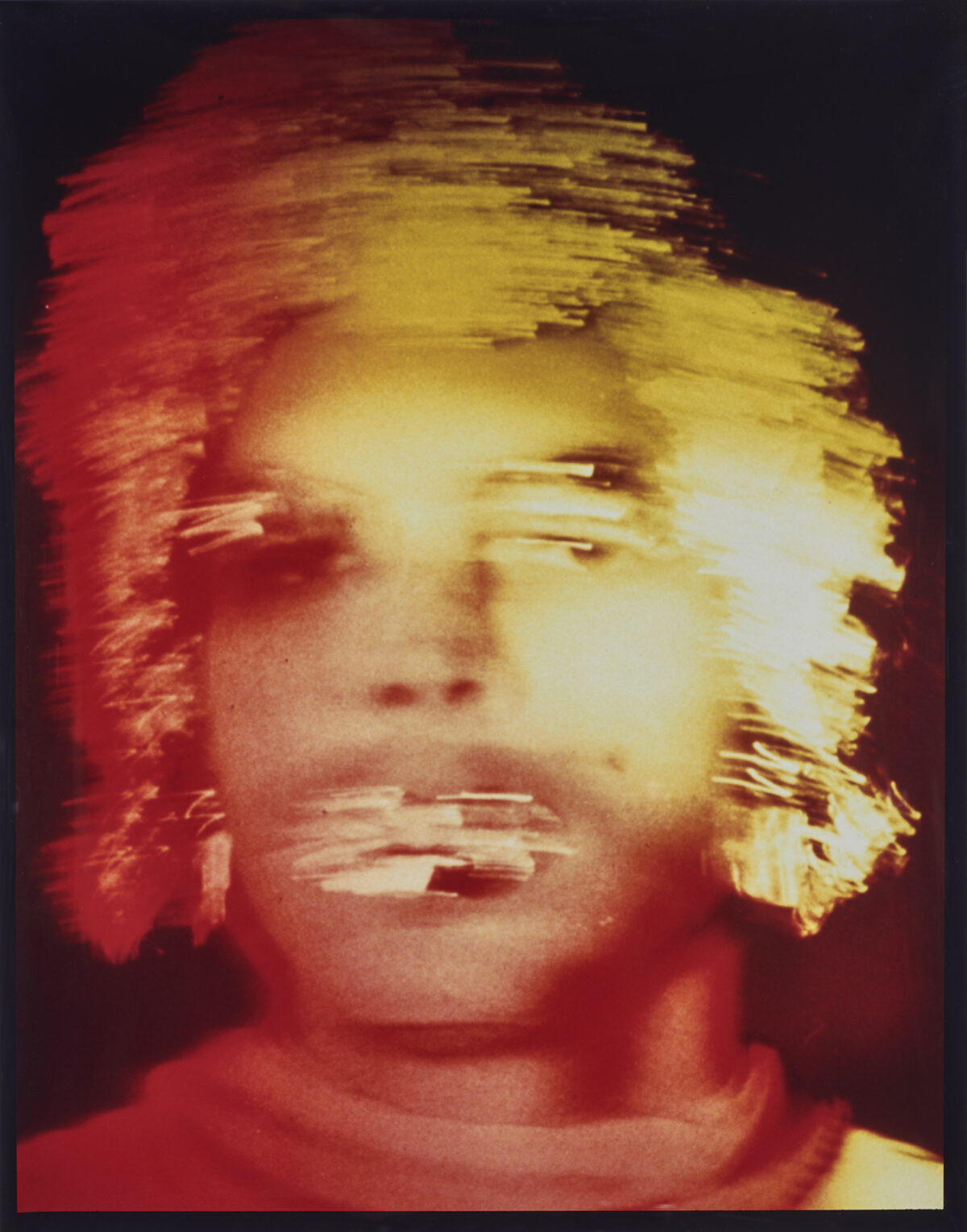

D’Amato pulls arresting shots from the difficult existence of a street prostitute or a single parent living in a slum, but most of his images build upon a narrative of uplifting personal and spiritual transformation, expressed by the exhibition’s title, We Shall, which refers to a classic Civil Rights anthem but also to Paul the Apostle’s writings on the Resurrection. The images of churchgoers in their Sunday clothes, of baptism allegories in public pools, and of divine light shining into sitters’ eyes, heighten the motif of religious salvation.

Exhibited in the art museum of a Catholic university, which was the site of Civil Rights unrest and organizing in the late 1960s, D’Amato’s journalistic images, which are formally conventional and even beautiful within the frame, are anything but neutral art objects. The sitters sit patiently, seeming to wonder who will co-opt their stories next.