Since the invention of the medium, photographers have used the tools at hand, from stereoscopes to cell phones, in an effort to convey the reality of war and conflict, both on and off the battlefield. The pictures are never pretty, but they are necessary, and War/Photography, the expansive show now at the Brooklyn Museum of Art, shows why.

Curated by Anne Wilkes Tucker and her team at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, the show is organized at the Brooklyn Museum by Tricia Laughlin Bloom, associate curator of exhibitions. Organized thematically – Civilians, Children, Refugees, etc., — the show includes more than 280 photographers from 28 countries. There are some famous images on view, including Joe Rosenthal’s photo of the soldiers mounting the American flag at Iwo Jima and Roger Fenton’s much-analyzed Valley of the Shadow of Death, which has absorbed photography historians with the question of whether Fenton staged the image and moved the cannonballs littering the valley floor during the Crimean War. But the majority of photographs are by lesser-known photojournalists and even military photographers.

Many originally appeared in newspapers or magazines, but some, like Kenneth Jarecke’s Incinerated Iraqi, taken in 1991 during the first Gulf War, were deemed too graphic for the public to see, at least in the U.S. Will Michels, a photographer and one of the co-curators of the show, called the image of the burnt corpse of an Iraqi soldier trapped in an incinerated truck, one of the most important photographs in the show. It’s horrifying and shocking, and that’s the reality of an ongoing conflict that moved in and out of the headlines.

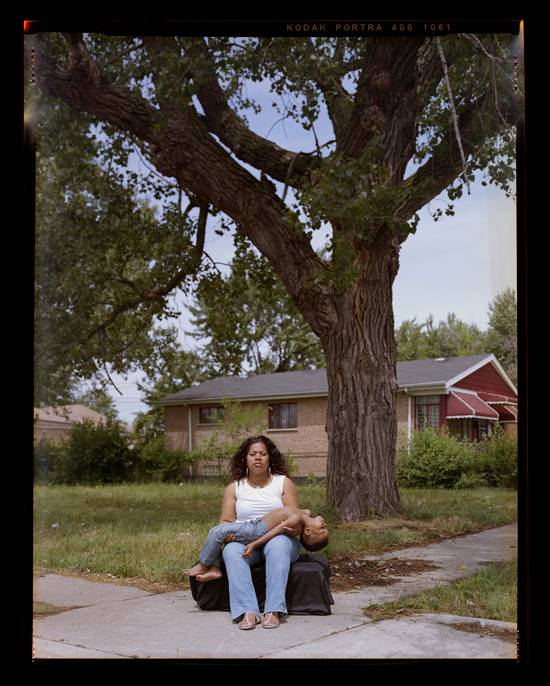

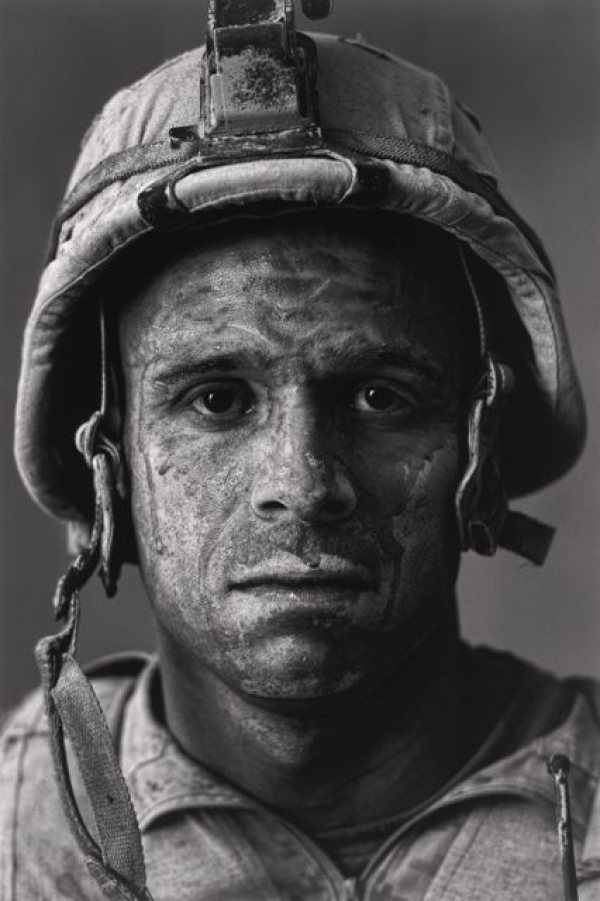

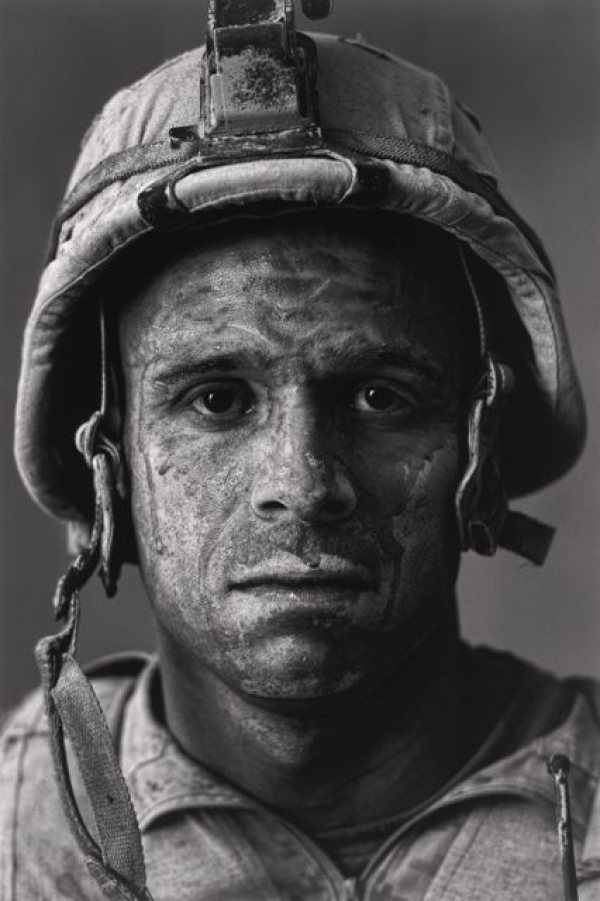

Less graphic and equally devastating are images that try to convey the long-term effects of war on soldiers. The thousand-yard stare of U.S. Marine Carlos Orjuela, serving in Afghanistan, in a photograph taken by Louie Palu, captures the flat, unfocused gaze of the battle-weary soldier. Then there are the photographs that represent so-called collateral damage. Rape, long used as a tool of war, is a subject difficult to represent in photographs. Jonathan Torgovnik’s series Intended Consequences focused on some of the many women who were raped during the Rwandan genocide. The women and their children were then shunned by their families and communities.

The product of ten years of research by Tucker, Will Michels and Natalie Zelt, curatorial assistant of photography at the MFA, Houston, the show is as important as it is disturbing.