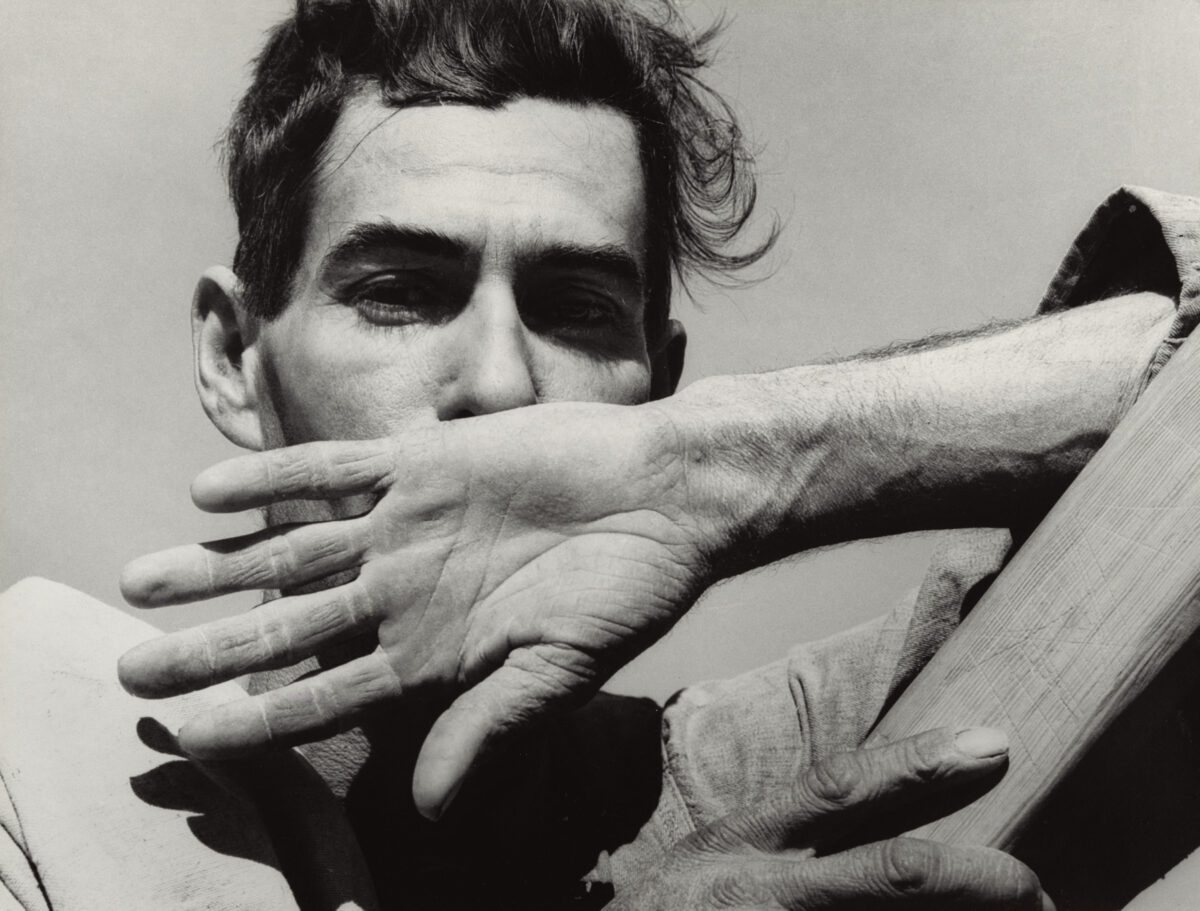

The fog-misted abodes of Todd Hido’s early photography, a late-1990s series called House Hunting, are evocative exercises in existential noir. The nighttime images depict windows glowing in desolate, aging neighborhoods. The photographer’s perspective is that of a lurker, a voyeur, longing to know what is going on inside those houses, onto which viewers can also project their own imagined narratives. The roles of the photographer and viewer are entwined, giving the pictures their punch.

In the expanded 25-year purview of this handsome mid-career survey, on view at Casemore Kirkeby through October 29, these pictures become part of a less ambiguous, erotically charged cinematic narrative. In recent years, the female figure has appeared, in various states of dress, power, and distress, in the context of the earlier location shots. For these works, all untitled, he casts models in the role of aspiring starlets, and bathes them in atmospheric color. A blonde in a powder blue sedan, a brunet femme fatale in a camisole. A 2009 photograph depicts a woman wearing red stockings, black pumps, and nothing else, as she reclines on a stained white carpet, and – classic noir – a 2012 black-and-white photograph of a bleach blonde resting a pistol across her bare chest.

The exhibition is titled, like Hido’s new monograph, Intimate Distance, a moniker that suits the material all too well – the works are close-up and steeped in artifice. The 32 works, from the late 1990s to 2016, are stylishly installed, and Hido fractures the narrative as he mixes sizes and subjects, photographs of moody landscapes, an image of a blazing red neon sign, and scans of what appears to be a scrapbook. One page reads, in cursive watercolor script, “stupid, worthless, nothing,” an odd, unattributed non-sequitur.

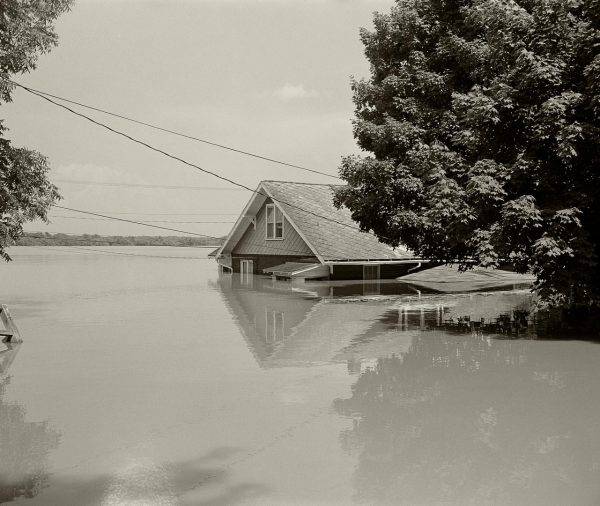

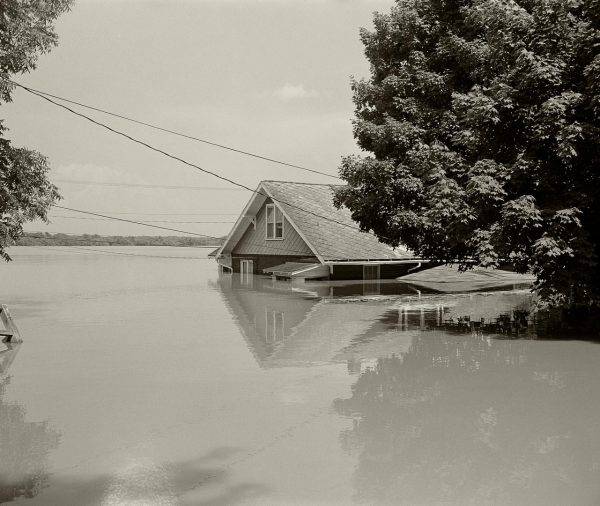

The show’s veneer is sophisticated, but it’s disappointing to see the mystery of those early works, so moody and psychologically rich, appear to become sets for standard Hollywood fantasies. More interesting is the work in an intimate side room, styled as a cool gray office, which contains black-and-white pictures – some never before shown early works – that speak to a sense of calmer desolation. In particular, Untitled #601, 1994, an image of an A-frame house impassively submerged by a flood, offers a scenario where the sense of drama seems most authentic.