This was easily the most unsettling photographic project on view in New York this fall. The hints had been there all along in Thomas Demand’s work, but in some sense the subjects of those pictures had obscured the full implications. No running away now. As everyone resident on the art planet knows, Demand has carved out a niche in photography by creating minimal paper and cardboard models of culturally loaded mises-en-scene (the tunnel where Princess Diana was killed, the Oval Office of Barack Obama) and photographing them. These “documents” have a peculiar status. Stripped of much of their specific information, they seem like postcards from the future, when viewers will no longer recognize, much less identify with, what is depicted. In a sense, this is the fate of photographs, to lose information the farther they are in time from their audience. That’s one interpretation. The other has to do with the circulation of images in the mass media, so common that their vague outlines form a kind of test pattern to our consciousness.

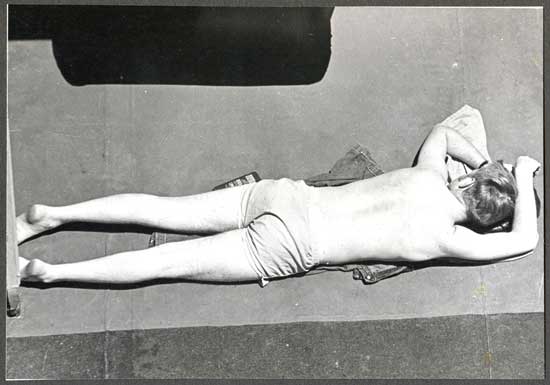

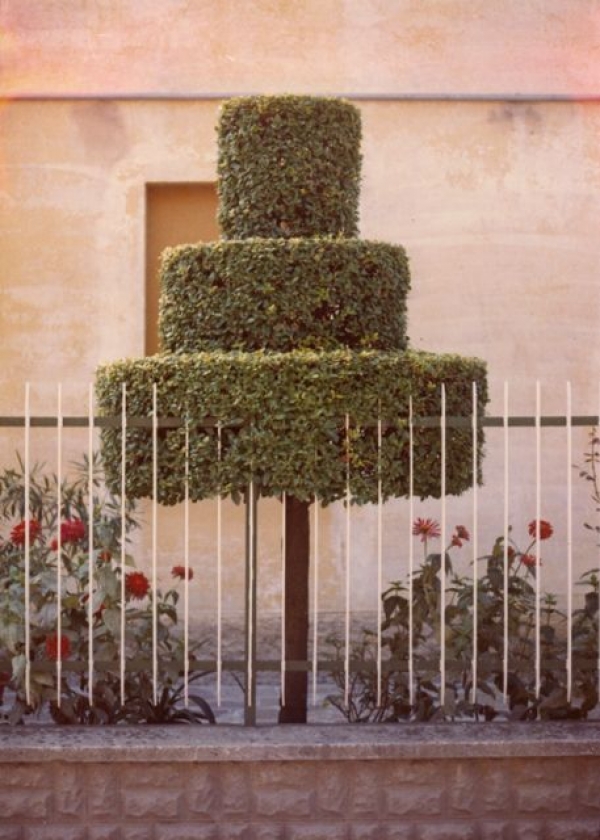

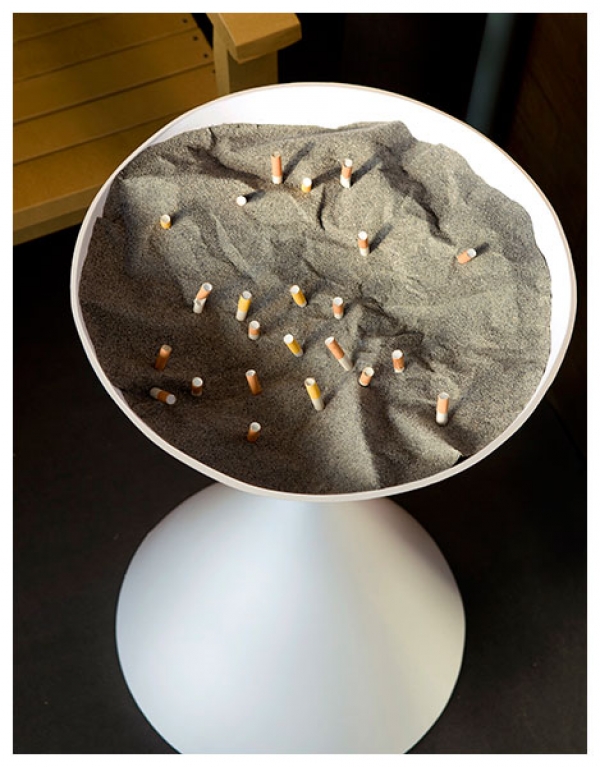

All these works presumed a fairly straightforward role for the camera at a literal level and an only slightly more complicated one for photography generally, involving memory on the one hand and desire on the other (why look?). “Dailies,” at Matthew Marks through December 21, turns the photograph itself into a paper model. Demand’s method hasn’t changed but his focus has shifted. Photography is the subject, and the unsettling question has become: why are we taking all these pictures? For some time Demand has been shooting with a cell phone camera, and these diaristic images serve as models for the recent work. He selects the images from his archive (say, a paper cup stuck in a fence or cigarette butts in a floor ashtray), then recreates them in paper and photographs the new scene. The simplicity and quotidian character of the subjects reflect the possible influence of the Italian photographer Luigi Ghirri, whose eye for the ordinary most often focused on events of representation in the real world. Even more prominent, however, is Demand’s engagement with cell phone photos – their celebratory triviality, ubiquity and stereotypical character. We’ve seen all these “dailies” a million times on the Internet, as a younger generation grows up ratifying the facts of existence with a picture. “Ratify” is really too strong a word. The generic blankness of Demand’s images suggests that no ghosts of memory or longing haunt photography today, only a desire to register some slight epiphany. It caught your attention for a moment, the concatenation of time, light and form. Perhaps there was a mystery there, or an oracle about to be delivered. It was beautiful, wasn’t it? But then you moved on.