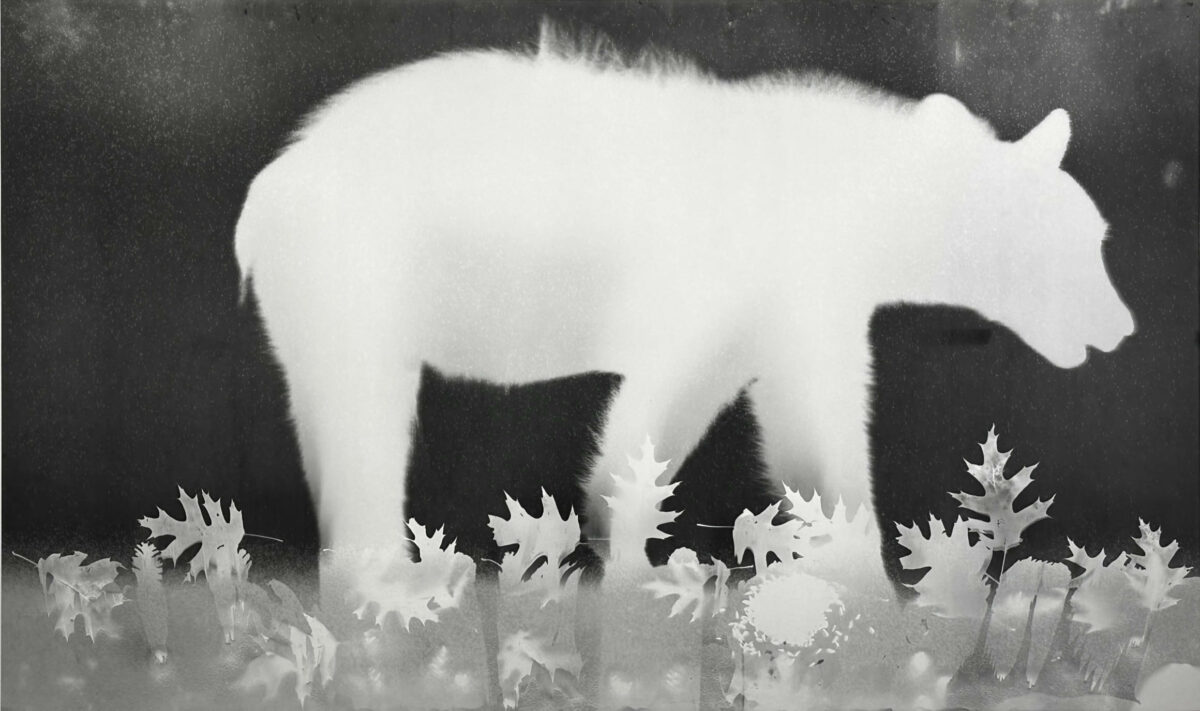

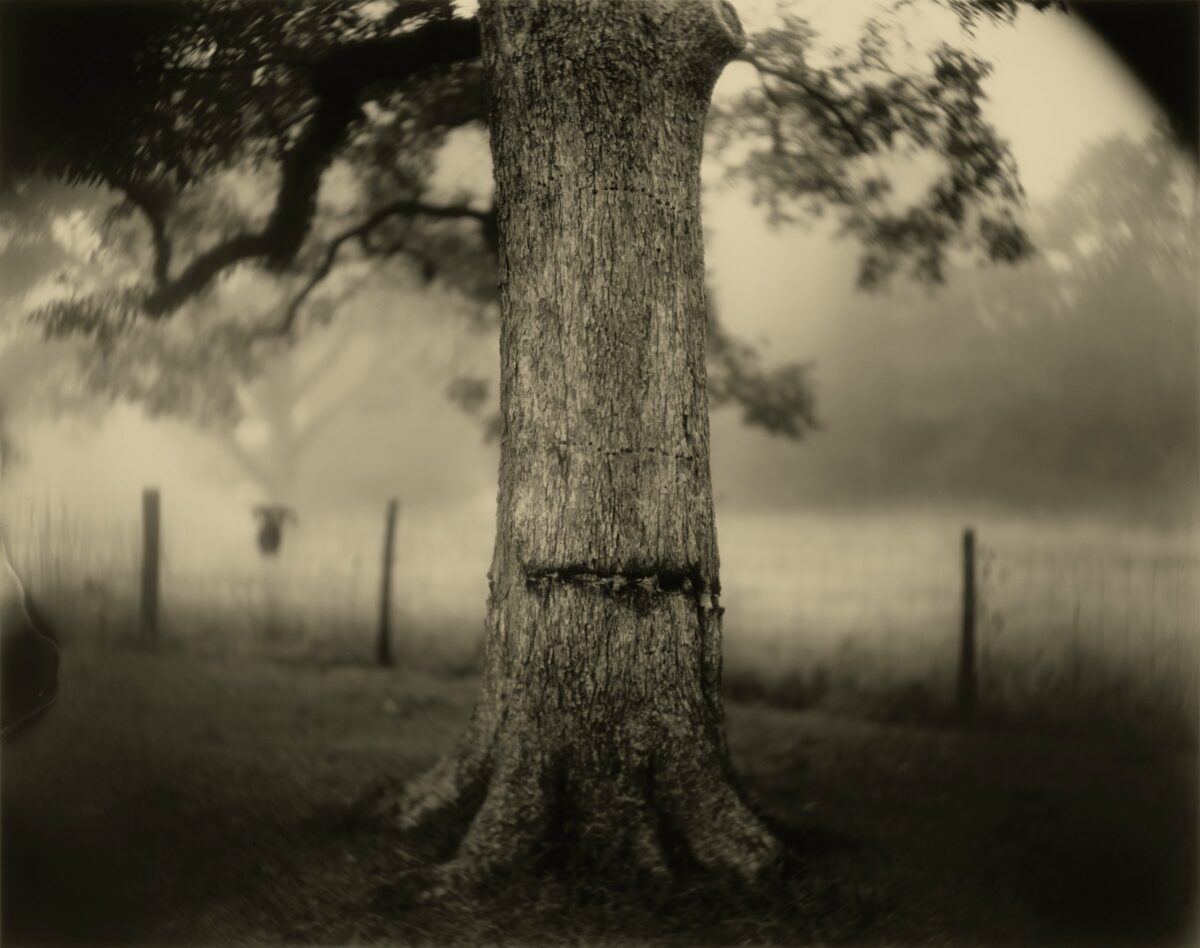

Rick Wester cast his net wide for his current exhibition, on view through November 2, to include painting, drawing, sculpture, and photography, and the results are equal parts eerie and entertaining. From taxidermied humanoid creatures and fantastical digitally constructed photographic scenarios to playful sketches on paper, the show explores what it means to be human and how we anthropomorphize, or distance ourselves, from our animal counterparts, physically and psychologically.

The half-beast, half-human creature is one of the most resilient tropes in myths and stories, from Pan and Puck to Mr. Tumnus in the Narnia stories. We can now add Kate Clark’s lifelike sculptures of animals with strangely beautiful human faces to that list. Bewitched and bewitching, they seem to have trotted right out of a fairy tale and found their way to Chelsea.

More liminal creatures are found in Meghan Boody’s fantastic scenes of fairy tales gone awry. It’s not for nothing that vampires, witches, wizards and princesses are fueling a fair amount of contemporary cultures at the moment, from Twilight to True Blood to Once Upon a Time. With themes of good and evil, lust and disgust, the transformative possibilities of fairy tales are enthralling. Boody’s unsettling scenes are full of disturbing details, like the long tail snaking its way from underneath a beautiful woman’s backless red gown, signifier of her in-between state, neither one thing nor the other.

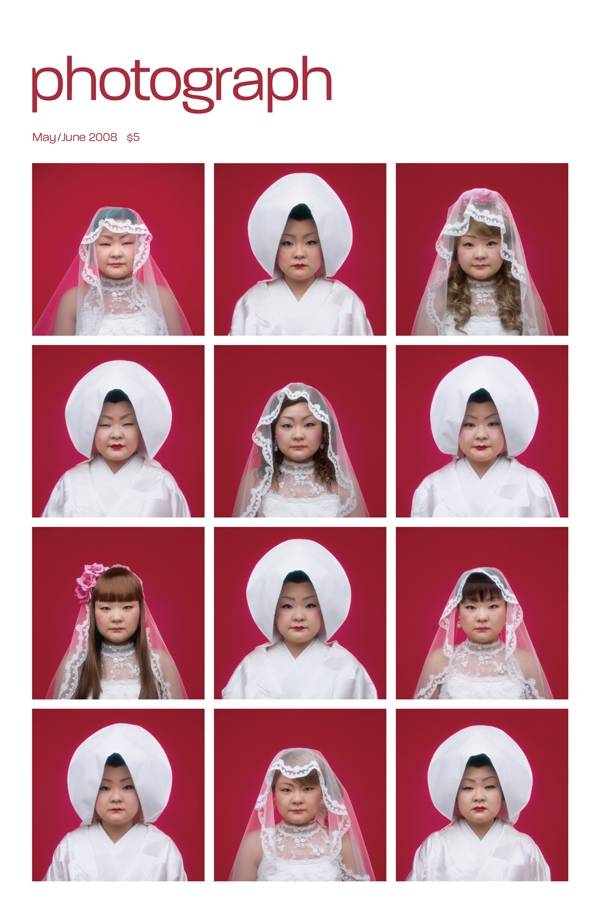

The show casually shifts gears between the uncanny work of Boody and Clark and the light touch of Japanese artist Kumie Tsuda, whose clay sculptures and childlike pastel drawings – of raccoons, skunks, a squirrel with its cheeks filled with nuts and a surprised cat – have a quirky immediacy. And in Christian Vogt’s playful Sugar Rabbit, a red gummy bunny and a red gummy hunter lean in towards each other for a kiss in an absurdist gesture of confectionary forgiveness.

The rhinoceros in Martin Wittfooth’s Smoking Barrels looks far less forgiving: it has a target painted on its wrinkled hide. And Tanja Verlak’s black-and-white photographs of animals in a zoo are pure heartbreak– a spotted cat seen behind dirty glass, a giraffe in a space enclosed by a chain-link fence. Verlak has photographed in and around zoos in Eastern Europe and the U.K., and her photographs foreground dirty windows, brick enclosures, and feeble fences; the lonely looking animals behind them are an afterthought, maybe the saddest comment yet on our objectification of our fellow creatures.