In 1993, promptly after the dissolution of the Soviet Union, Richard Pare embarked on a quest to document the empire’s early flirtations with modernist architecture, the extent of which was largely unknown beyond its borders and shunned within them. Constructivist architecture briefly flourished there in the decade between 1922 and 1932. Pare’s exhaustive cataloging impulse—he was the founding curator of the Canadian Centre for Architecture’s photography collection—resulted in a 17-year project and a photo archive of about 15,000 images of Constructivist masterworks. Of these, 88 are on view in The Lost Vanguard: Soviet Modernist Architecture, 1922–32 at the Graham Foundation in Chicago (through February 16).

Pare’s documentary approach is generous and lucid: he knows that this is likely the viewers’ first contact with these structural wonders, and his big, crisp, immersive color prints both captivate and educate. But the photos are also architectural portraits, with Pare capturing the character and sensibility of these aged matrons of modernism. In a handful of images, Pare modestly crops architectural details to produce elegant, formal compositions, recalling the power and freshness of the bold Constructivist designs and their faith in pure geometry.

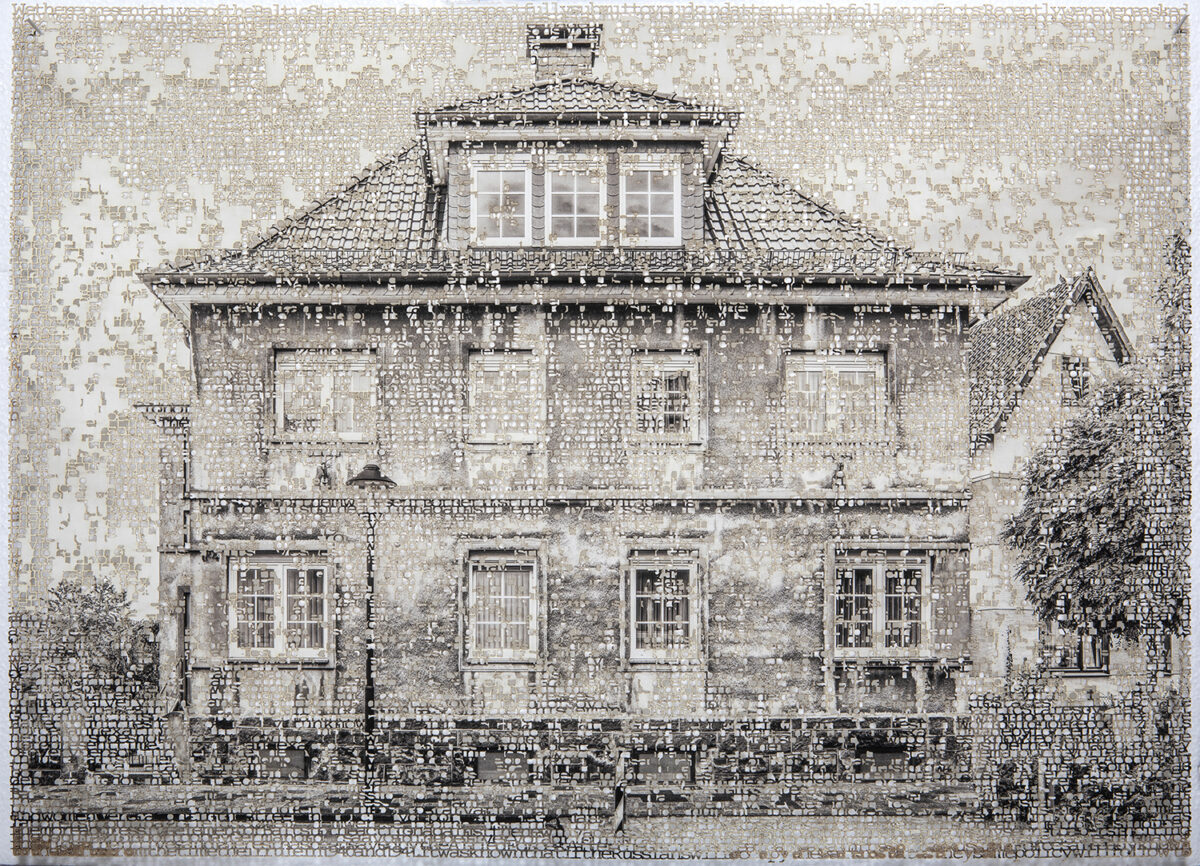

The so-called “ruin porn” genre of photography solicits a range of responses, from moralism to nostalgia to schadenfreude—all especially apropos in the context of the Soviets’ failed utopian society—but Pare’s images resist such heavy-handedness. Instead, they reveal a young nation’s fantasy of rethinking its citizens’ quality of life and participating in an international, progressive, and cosmopolitan cultural community. The shells of that modernist ideology remain, with people living in and among these buildings, though many are threatened by destruction, in the contemporary cities of the former USSR. The multidimensional legacy of modern living is made even more concrete by the exhibition’s installation on three floors of the Madlener House—itself an architectural gem and the Graham Foundation’s headquarters. Hanging above the mansion’s fireplaces, in stairwells, and a in dining room adjacent to an architectural artifacts garden, Pare’s photos of faraway ideals are nested in our collective, ever-present built environment.