The title of this exhibition of more than 120 images by Alvin Baltrop feels erroneous. The Bronx native’s work, which focused predominantly on a subset of gay society who met at New York City’s dilapidated shipping piers along the Hudson River in lower Manhattan in the 1970s and early ‘80s, feels more about a specific place and time than about Baltrop’s life. And while the exhibition does include some of his personal belongings – a camera, press pass, exhibition posters – it doesn’t do much else to explain the artist’s fascinating life, one that included service in the Navy and jobs that ranged from a street vendor and cab driver to jewelry designer.

Although many of these images have never been seen before, Baltrop’s photographs from the piers have been shown in recent years (some were included in the Greater New York exhibition at MoMA PS1 in 2015-16). They remain compelling, highlighting, as Baltrop moves closer to his subjects, a profound sense of trust between the photographer and his models. These portraits, after all, were taken during a time in which many subjects were probably not ready to have their intimate lives made public.

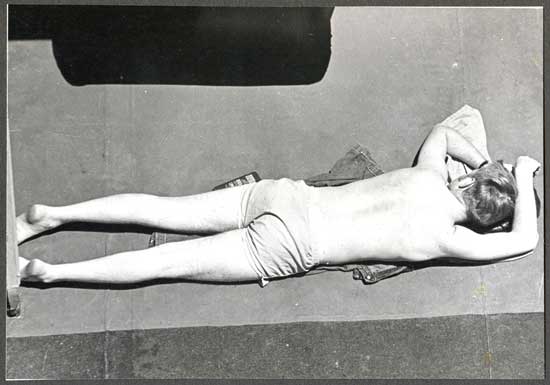

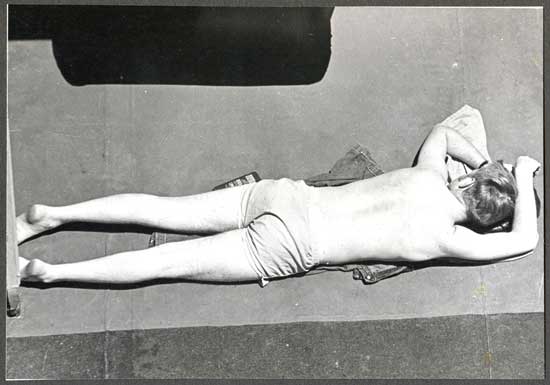

On view through February 9, the exhibition begins with photographs that Baltrop (who died in 2004) took during his time in the U.S. Navy, from 1969 to 1972. Many of these foreshadow the homoerotic imagery that essentially defined his career. The rest of the show includes pictures taken along the piers, some printed small, others showing markers of age (watermarks, torn edges, etc.) but all demanding the viewer’s gaze.

One takeaway of the exhibition is a sense of nostalgia for an era when New York City was run-down and dangerous. Today we romanticize it, and there’s the sense that Baltrop may have as well. His work feels relaxed and deliberate and consists of cinematic landscapes that feature the dilapidated piers and downtown bars, sometimes with the Manhattan skyline as a backdrop. The ways in which the men are framed in the images demand a second glance. At first, they feel subsumed within the landscape, but a closer look elicits a sense of eroticism as the viewer begins to understand the sexual activity behind their presence here.

It’s clear that Baltrop connected with the people he photographed, and while the setting may be on the fringe of society, he empowered his subjects. It’s thrilling to see an overlooked artist get recognition, yet this viewer was left wanting to learn more about Baltrop’s iconoclastic life and work.